Ertach Kernow - Tragedy and death at Wheal Owles

Tragedy at Wheal Owles

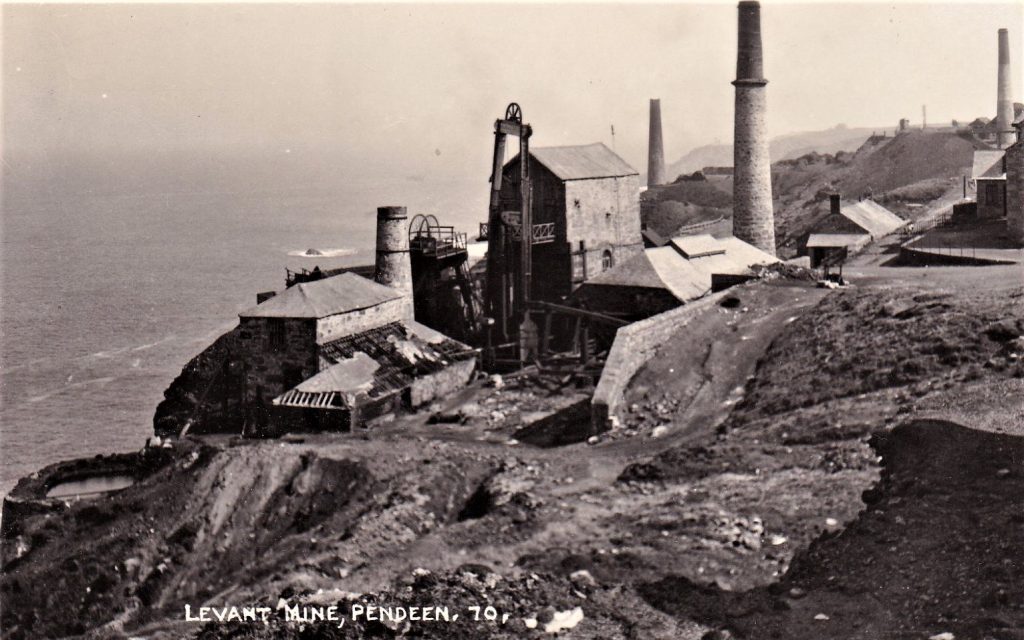

Cornwall’s coastline and its scenery is a wonderful thing to behold for those taking the coastal footpath or just visiting a particular site along the way. Besides the beaches, interesting coves and cliffs with the sea either gently lapping or during storms ferociously battering them there are a huge variety of beautiful and interesting sights to enjoy. Cornwall’s industrial past is highlighted by the multitude of engine houses making up the historic Cornish mining heritage.

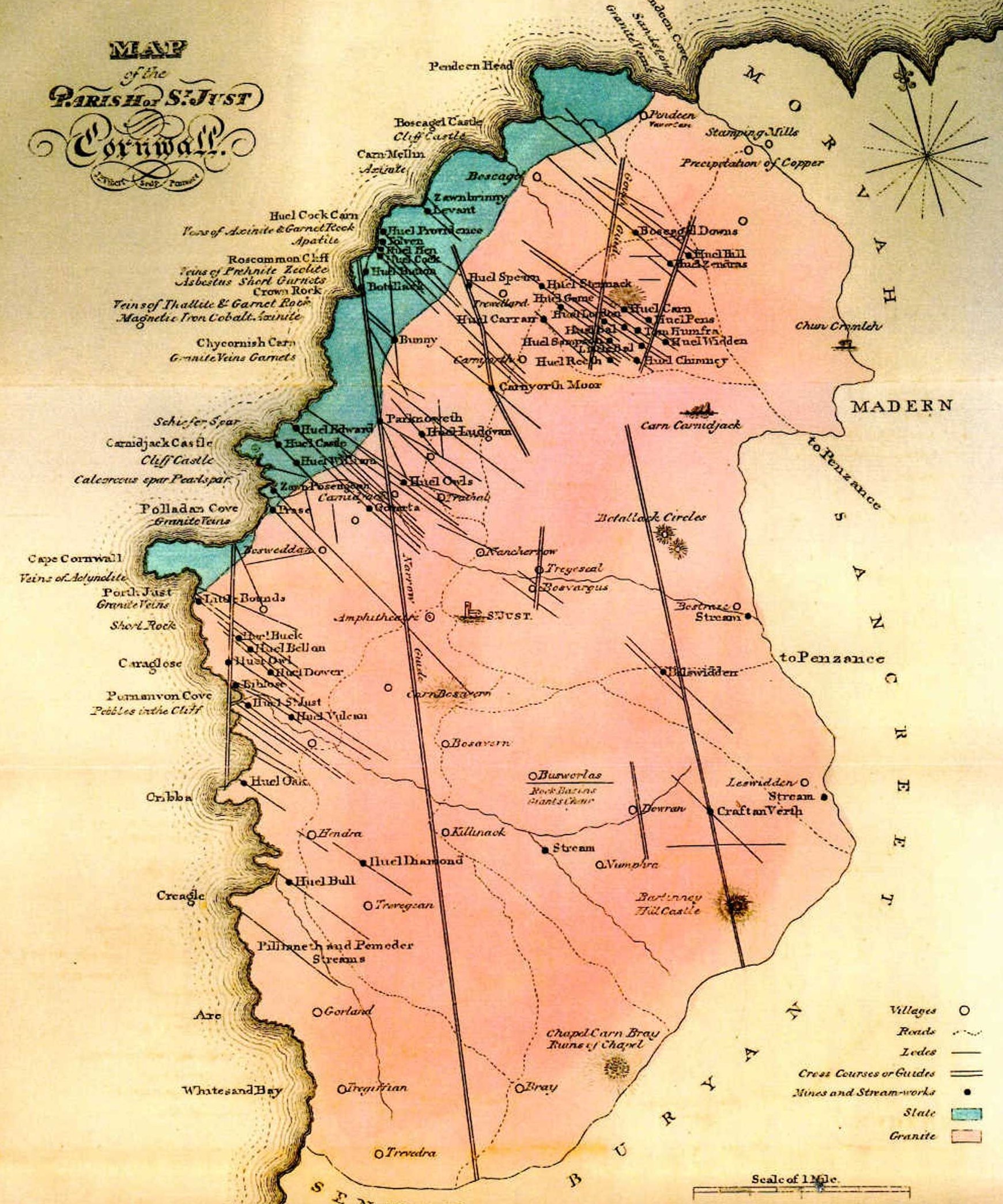

By the 1860’s Cornish mining production had reached its peak with increasing curiosity in Cornwall’s mines from many people, including academics and writers. In 1846 Queen Victoria had visited the Polberro Mine at St Agnes, which was afterwards renamed Royal Polberro Consuls. She also visited Botallack, which even through the grime of industrial production would have looked romantic with the engine houses perched close to the sea on the cliffs. This helped encourage mining tourism where hundreds of people visited and descended mines each year. Botallack where the mine workings stretched far out under the sea was a popular destination. The Scottish author R M Ballantyne, perhaps best known for ‘Coral Island’ published in 1857, which inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’, visited Botallack on several occasions. His novel ‘Deep Down: a Tale of the Cornish Mines’ published in 1868 was acknowledged as possibly the most informative and accurate on the lifestyle and techniques of 19th century Cornish miners.

As always click the images for larger view

What was actually taking place deep down in Cornish mines would not be seen until the 1890’s. Although shared through descriptive text as novels for the general public and mining journals often with some drawings, the extent of the work and conditions could not yet be fully realised. It was J C Burrow a Camborne photographer who would best illustrate miners working with his series of photographic images in 1893. These really captured the Cornish miner toiling within his environment.

In July 1843 the Penzance Gazette had an article where it began; ‘Our columns, week after week are more or less occupied by reports of fatal mine accidents, a repetition of which, by a little of ordinary precaution, might be avoided. No individual can read such sad statements, without deeply lamenting that the hard-working miner should be so often in jeopardy, and feeling desirous that some precautionary measures should have recourse to. The accidents we more particularly allude to, are not such as that we recorded last week as having taken place at East Wheal Rose, by the visitation of Providence but such as occurred last week at Wheal Vyvyan mine and at Boreas granite quarries, in the parish of Constantine, and at Wheal Level, in the parish of St. Kevern, notices of which appear in another column.’ In due course safety matters would be better addressed, but many adventurers as investors were known seemed more interested in dividends than the wellbeing of the workers unless it resulted in losses of profit.

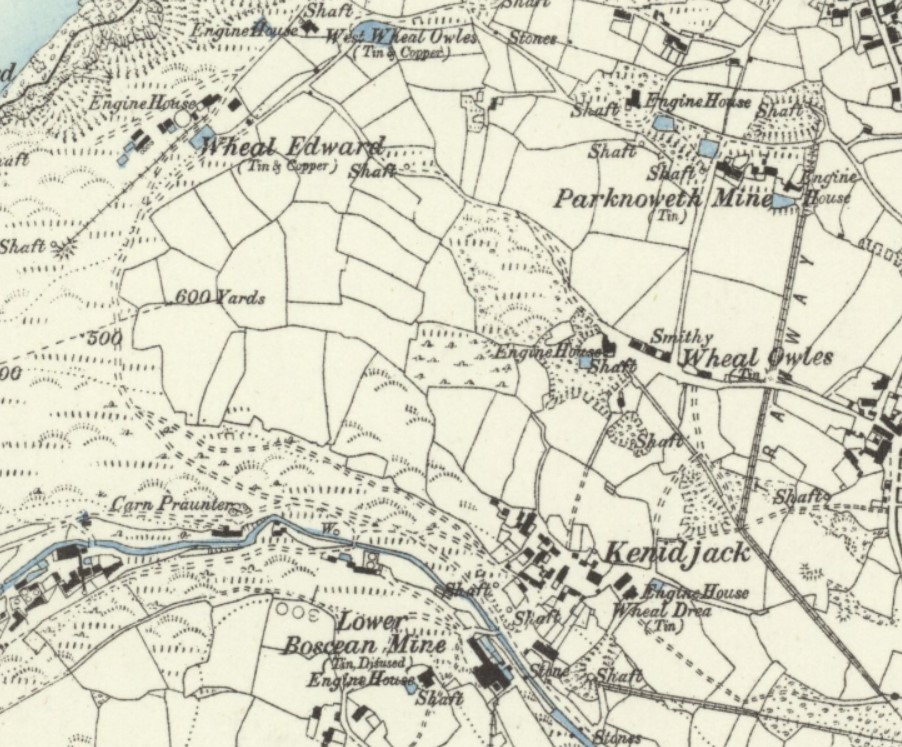

It is difficult for us today to fully appreciate the danger and hard work of these miners as we observe some of these thought-provoking engine houses in their ruinous state, but some also have sad tales to tell. Well-known are the disasters with tragic loss of life with 39 drowned inland at the East Wheal Rose Mine at St Newlyn East, flooded in 1833. Later at the Levant Mine in 1919 following the collapse of the man-engine whilst transporting men to the surface 31 men died. Perhaps less well known was the loss of twenty lives at Wheal Owles, near to the better known Botallack mines near St Just. Here at the Wheal Owles sett, the legal boundary within which a mine could extract minerals, mine workings were very close together and therein lies the tale of this disaster.

Over the preceding decades there had been a series of accidents at Wheal Owles, much as elsewhere in the Cornish mining industry, with deaths and maiming’s amongst the miners. In September 1840 Edward Warren met a grisly death whilst digging out a charge, which having failing three successive times to explode then went off. The coroner was informed ‘a copper bar passed through his head and literally smashed him to pieces’. James William Hocking, a thirteen-year-old boy working as a miner, fell sixty feet whilst climbing the ladder following his shift. Death by falling whilst climbing out of a mine after a hard day’s work was not uncommon even for hardy experienced men. 1842 saw Nicholas Grenfell and Henry Chappell dying of suffocation at Wheal Owles. Three years later William Oats was seriously injured losing his right hand and his sight when an unexploded charge from the previous day exploded whilst being bored out. The following year 18-year-old Nicholas White was killed when he appeared to have fallen 40 fathoms (240 feet) and was found at the bottom of a shaft. James Eddy was counted lucky to live in 1852 when a charge suddenly exploded breaking his legs and inflicting other injuries. His sight was not much affected. Over the decades many more such incidents had and would occur at Wheal Owles until that fateful day in 1893.

The breaching of the Wheals Owles and Drea divide caused an immense rush of water into the 65th fathom level, from the combined flooded Wheal Drea and Boscean mines. Candles by which the miners worked were blown out by the rush of air pushed before the onslaught of water as men rushed in the dark to escape. Those below the 65th level had little chance as water poured in a deluge down into the deeper workings.

A survivor’s statement from James Hall's was published as follows: ‘I have been working for 17 years in Wheal Owles and on Monday morning I went below as usual to the 55 in the Cargotina shaft. Each one went to his work and, about half an hour afterwards, the collapse of ground occurred without any warning. I heard the shock. and said ` That is the sollar (a small, boarded platform at the base of a ladder within a shaft) and, after thinking for a moment, I said, 'It is water' and I jumped to the level; but no one could carry a light. We could not do any more, but we put three men in the waggons, after going back in the dark and trammed them back to the shaft. There were one or two boys whom I rescued and brought back to the ladder-road, and I also went back and rescued another missing man. I then struck a light against the pump and tried to rescue the others and heard someone sing out `Farmer, bring a light' [Farmer is Mr. Hall's nickname]. This cry was repeated several times, and I followed it until I got to the 40-fathom level when I could not hear anything more.' James Hall was the last man to leave Wheal Owles.

Other deeds of heroism were carried out on that fateful day, only 30 minutes had elapsed between the water breaking in and the flooding of the mine. The mine captain Richard Boyne was charged with not keeping accurate plans of the workings and brought to trial. An old and very sick man he was fined just £15. It seems that the lode being mined in both Wheal Owles and the Drea mines were one and the same and Boyne’s calculations had shown 114 feet between the two mines. An attempt to later reopen the mine failed to materialise and the workings were finally abandoned forever.

Another sad tale of a mine where the investors often made money and miners paid the price through injury and death.

Click to see the article on J C Burrow: Cornish photographer

![[186] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 24.01.2023 - Cornish cultural surveys, talks and activities around Cornwall Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 17.01.2023 - Cornish cultural surveys, talks and activities around Cornwall](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/186-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-24.01.2023-Cornish-cultural-surveys-talks-and-activities-around-Cornwall-283x300.jpg)