Ertach Kernow - Unsentimental journey to the Lizard

Travels around Cornwall by what might be termed early tourists were often by writers or topographers out to sell books or their maps. Most of these were men although here in Ertach Kernow we have been following the travels throughout Cornwall of Celia Fiennes in 1698. Another woman, novelist Dinah Maria Mulock Craik wrote ‘I had always wished to investigate Cornwall. This desire had existed ever since, at five years old, I made acquaintance with Jack the Giantkiller, and afterwards, at fifteen or so, fell in love with my life's one hero, King Arthur.’ Describing her interest in, ‘that grandest, wildest, most dangerous coast, the coast of Cornwall.’ Dinah Craik began her tour with friends starting in Exeter on 1st September 1881, entering Cornwall by train over the relatively new Royal Albert Bridge, completed in 1859.

She described the first part of her journey thus, ‘I shall long remember, as a dream of sunshiny beauty and peace, this journey between Plymouth and Falmouth, passing Liskeard, Lostwithiel, St. Austell, &c. The green-wooded valleys, the rounded hills, on one of which we were shown the remains of the old castle of Ristormel, noted among the three castles of Cornwall ; all this, familiar to so many, was to us absolutely new, and we enjoyed it and the kindly interest that was taken in pointing it out to us, as happy-minded simple folk do always enjoy the sight of a new country.’ Lovely landscape description, not perhaps the ‘simple folk’ although she was advised by an old chap to ‘take care, they're sharp folk, the Cornish folk, they’ll take you in if they can.’ Also. ‘They'll be sure to ask you double the money, but never you mind! refuse to pay it, and they'll give in. You must always hold your own against extortion in Cornwall.’ So, maybe not that simple after all, a case perhaps of English tourists underestimating Cornish folk. At least she referred to Cornwall as a country.

Arriving in Falmouth there was a choice between the magnificent new Falmouth Hotel, with its table d’hôte, lawn tennis ground, sea baths and promenade, or the old-fashioned Green Bank with its sea views and comfort homely peace, which they chose. Advised by friends that ‘The Lizard is the real point for sightseers, almost better than the Land's End’ that is where Mrs Craik and friends headed. After being told that supplies might be scarce and not knowing what the Lizard was Mrs Craik described her preparations as, ‘I proceeded to lay in a store of provisions, doing it as carefully as if fitting out a ship for the North Pole.’ Having arranged a carriage from Falmouth for the following day the group took a wander around ‘the quaint old town – so like a foreign town’ before settling down for the night.

On day two of their tour the three ladies were fortunate to have engaged the services of a young man, the author named as Charles. Maria Craik wrote of him; ‘never failing when wanted, never presuming when not wanted, straightforward, independent, yet full of that respectful kindliness which servants can always show and masters should always appreciate, giving us a chivalrous care, which, being ‘unprotected females,' was to us extremely valuable, I here record that much of the pleasure of our tour was owing to this honest Cornishman.’

Travelling to Constantine Charles pointed out views to be seen ‘Just turn and look behind you, ladies, isn't that a pretty view?’ The ladies loved it, and Mrs Craik wrote ‘From the high ground we could see Falmouth with its sheltered bay and glittering sea beyond. Landward were the villages of Mabe and Constantine, with their great quarries of granite, and in the distance lay wide sweeps of undulating land, barren and treeless, but still beautiful.’ Charles took the ladies to the Trelowarren estate where Mrs Craik describes a Cornish mystery, which she regrets not having visited. ‘At Trelowarren, not far from the house, are a series of subterranean chambers and galleries, in all ninety feet long and about the height of a man. The entrance is very low. Still, it is possible to get into them and traverse them from end to end, the walls being made of blocks of unhewn stone, leaning inward towards the roof, which is formed of horizontal blocks. How, when, and for what purpose this mysterious underground dwelling was made, is utterly lost in the mists of time.’ Of course, what she was writing about was the Halliggye Fogou, all that remained of an early settlement on that site, one of the most elaborate and best-preserved fogou’s in Cornwall.

As they approached Lizard Town the ladies noticed curious rocks emerging from the turf which Charles informed them was serpentine. They spent an enjoyable hour wandering around on Goonhilly Downs collecting plants hoping they would take root back home in Kent. Arriving at their lodgings they had a very well received meal and sallied forth to explore the coves and cliffs becoming besotted with the blueness of the water took a boat trip. They were especially pleased to meet their boatman a friendly helpful sixty-year-old who gave his name as John Curgenven, which they struggled to pronounce. John pointed out various rocks with their names and stories including Kynance Cove and places where he said ghosts walked at night and the ships that were wrecked along that coastline. Landing at the lifeboat cove John told them ‘in many places along this coast, when there's a wreck, and we’ve called out, the parson's generally at the head of us. Volunteers ? Of course, we're all volunteers, except the coast-guard, who are paid. But they're often glad enough of us and of our boats too. The life-boat isn't enough. They keep her here, the only place they can, but it's tough work running her down to the beach on a black winter's night, with a ship going to pieces before your eyes, as ships do here in no time. I've seen it myself — watched her strike, and in ten minutes there was not a bit of her left.’ The lifeboat would later have a new station including a slip to launch the lifeboat and saving many lives.

Heading back guided by Charles and John they were introduced to Cornish Stone Hedges as a short cut back to their lodgings. The trip back was described so. ‘These hedges were startling to any one not Cornish-born. In the Lizard district the divisions of land are made not by fences, but by walls, built in a peculiar fashion, half stones, half earth, varying from six to ten feet high, and about two feet broad. On the top of this narrow giddy path, fringed on either side by deceitful grass, you are expected to walk! — in fact, are obliged to walk, for there is often no other road. There was none here. I looked round in despair. Once upon a time I could have walked upon walls as well as anybody, but now — ! ‘I'll help you, ma'am; and I'm sure you can manage it,’ said Charles consolingly. ‘It's only three-quarters of a mile.’ Three-quarters of a mile along a two-foot path on the top of a wall, and in this deceitful light, when one false step would entail a certain fall. And at my age one doesn't fall exactly like a feather or an india-rubber ball.’ Dinah Maria Craik was only aged 55, so not really what we would term old these days. So ended the first two days of Mrs Craik’s tour of Cornwall accompanied by her ‘ducklings’.

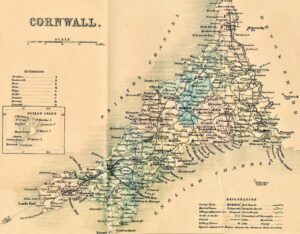

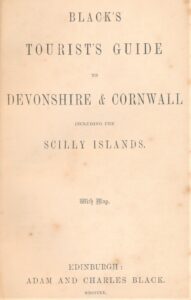

What was very different in 1881 from earlier travellers to Cornwall was firstly the entry to Cornwall. Journeying into Cornwall by train was just 22 years old and Newquay now a major tourist town had a railway connection for just five years since 1876. There was also the availability of guidebooks which were being distributed by a number of publishers. Murray’s Handbook for Travellers was first published in 1836 covering European and Asian destinations, but in 1851 ‘A Hand-book for Travellers in Devon & Cornwall’ was published. Guidebooks by the Edinburgh based publishers Adam and Charles Black began in 1839 and in 1855 they published their first edition of Devon and Cornwall. This was pretty brief with only 38 pages devoted exclusively to Cornwall. In 1871 Black’s guidebook covering Cornwall had evolved into the ‘Black’s Guide to the Duchy of Cornwall’ and was a larger far more informative volume. From the first Black’s guide relating to Cornwall in 1855 a map was included and it’s interesting that Newquay was not included, naming the settlement rightly as Towan. New Quay would not appear until 1871 and only as a brief mention of its fishing industry and two inns.

By the time of Mrs Craik’s visit in 1881 Cornwall’s tourist industry was well underway and people like Charles were finding employment as guides as well as in the growing number of existing and new hotels being built. During Mrs Craik’s visit to Falmouth there were four hotels mentioned. The historic Green Bank Hotel which had been running as an inn and hotel from the late 18th century and Falmouth’s oldest hotel and still operating. The relatively new Falmouth Hotel opened in 1865 and since then much extended, The Royal Hotel in the town centre latterly where the HSBC Bank was located before its closure in 2022 and the Albion Hotel now the Cutty Sark now run as a modern traditional inn in Grove Place. The earlier arrival of the railway to Falmouth encouraged the growth of tourism in this part of Cornwall.

![Ertach Kernow - Unsentimental journey to the Lizard [1] Unsentimental journey to the Lizard](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Ertach-Kernow-Unsentimental-journey-to-the-Lizard-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - Unsentimental journey to the Lizard [2] Unsentimental journey to the Lizard](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Ertach-Kernow-Unsentimental-journey-to-the-Lizard-2-254x300.jpg)

![[166] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 30th August 2023 - Harvest celebrations, Liskeard Unlocked, Royal Cornwall Museum talk Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 30th August 2023 - Harvest celebrations, Liskeard Unlocked, Royal Cornwall Museum talk](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/166-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-30th-August-2023-Harvest-celebrations-Liskeasrd-Unlocked-Royal-Cornwall-Museum-talk.jpg)