Ertach Kernow - Touring Cornwall with author Daniel Defoe

Cornish tours in earlier centuries were carried out by a variety of people, by order of the king in John Leland’s case, map makers and topographers such as John Norden and often by writers and artists. They entered Cornwall by ferry, at Cremyll in the case of Celia Fiennes or Saltash like JMW Turner, many over Cornwall’s historic stone bridges and Mrs Dinah Craik by railway in the late 19th century. We continue the journey of Daniel Defoe a most interesting man who was in turn a spy, political satirist and pamphleteer, merchant and as best known a novelist and author of Robinson Crusoe.

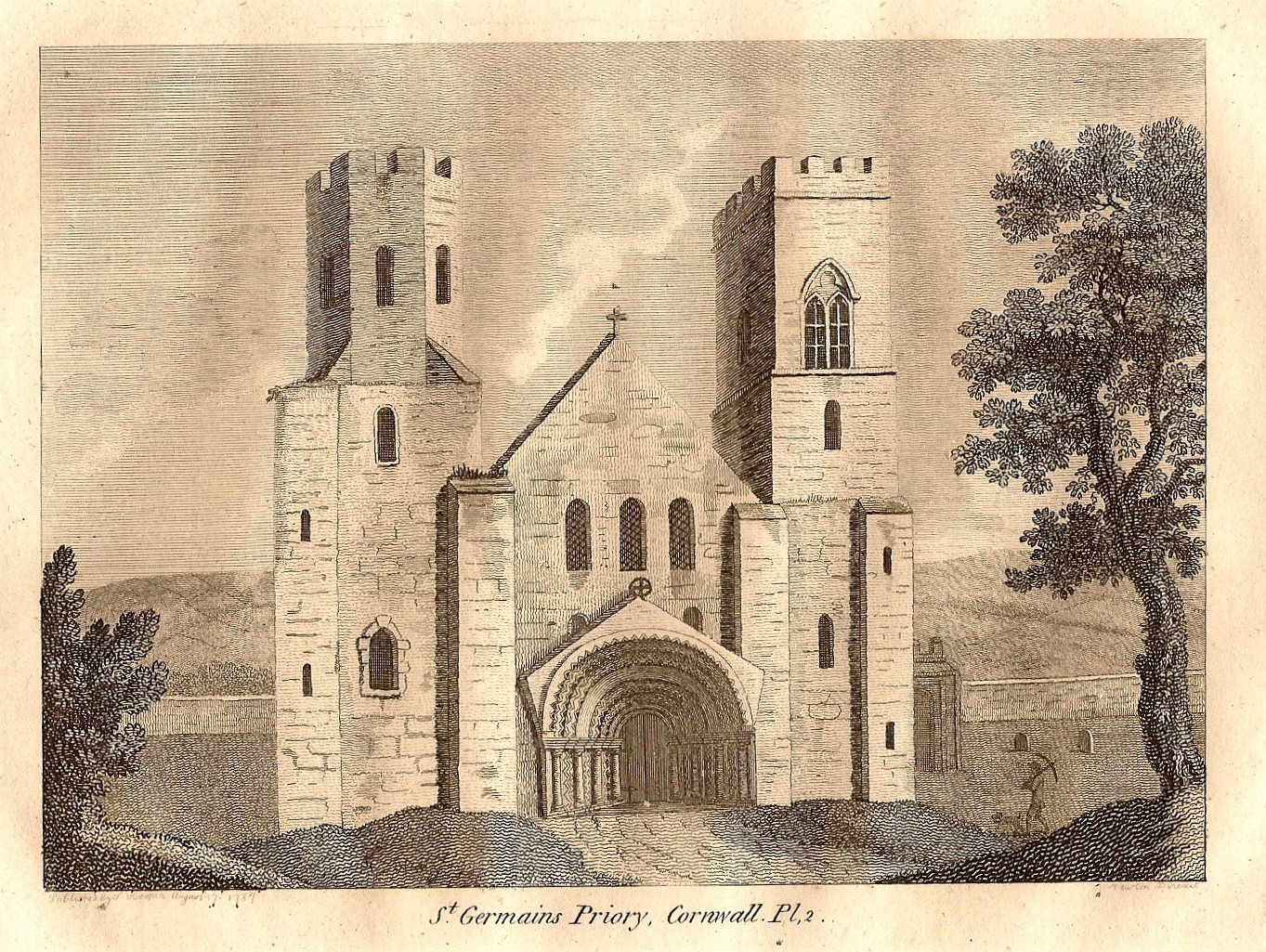

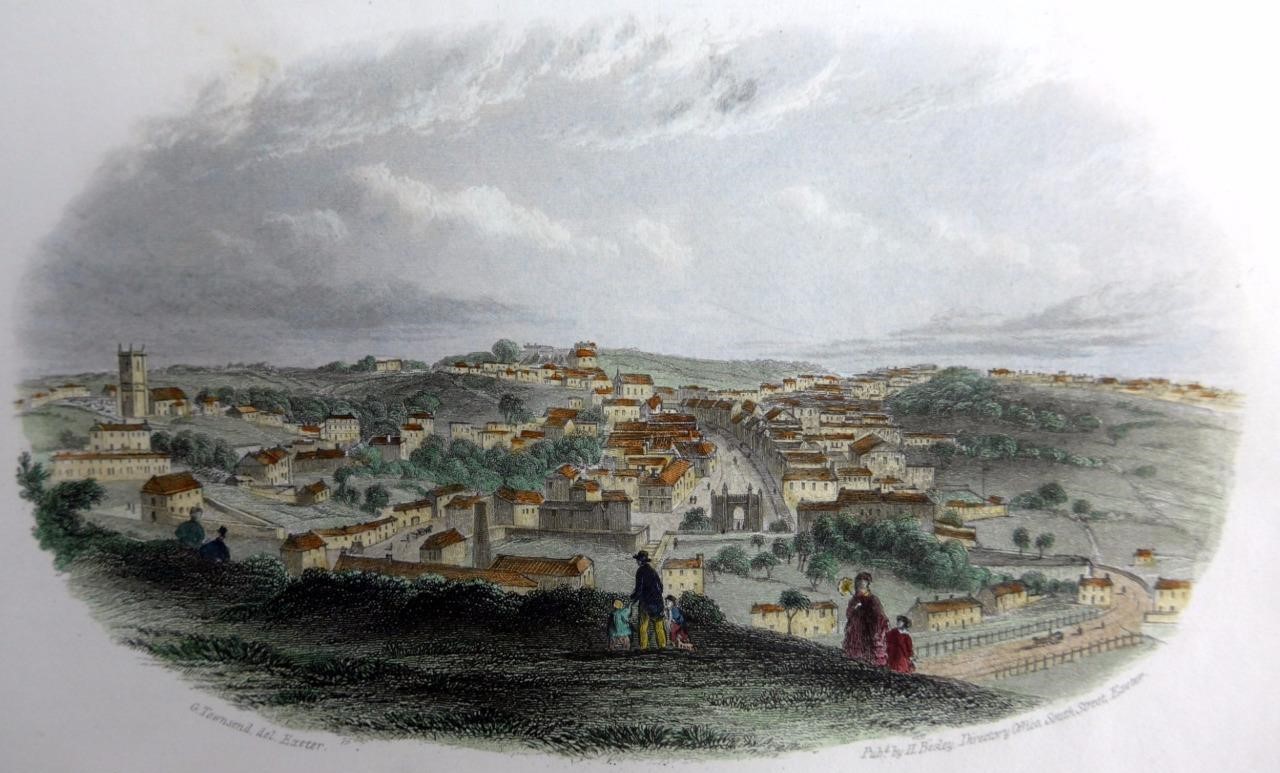

After crossing the River Tamar by ferry at Saltash Defoe travelled down along the south coast with slight diversions through St Germans, Liskeard, Fowey, Lostwithiel, Looe and Falmouth, where we last left him. He provides some very interesting information about these and other towns relating to their state of being, from St Germans and Lostwithiel which are decayed, to Falmouth which is flourishing. Of Truro he notes about port there ‘in the middle, between the conflux of two rivers, which tho' not of any long course, have a very good appearance for a port, and make a large wharf between them in the front of the town; and the water here makes a good port for small ships, tho' it be at the influx, but not for ships of burthen.’ Falmouth by Defoe’s time had taken most of the larger scale trade from Truro and the rivers there had begun to silt up. However, the Truro merchants had seen the writing on the wall and invested in wharves at Falmouth.

As always click the images for larger view

Daniel Defoe often noted whether a town had any nonconformist meeting houses or chapels. He had been led to writing through his religious beliefs and as a strong nonconformist, rejecting the Church of England. He had ended up in deepwater with Queen Anne following the death of the religiously tolerant Dutch born King William III, so much so he had been pilloried and imprisoned. Of Truro he said that it had ‘at least three churches in it, but no Dissenter's meeting house, that I could hear of.’ Although Truro is now the capital of Cornwall and the only city it is smaller than Falmouth, which no doubt will in time also engulf the ancient town of Penryn. Defoe wrote comparing them ‘The town {Truro] is well built, but shews that it has been much fuller, both of houses and Inhabitants, than it is now; nor will it probably ever rise, while the town of Falmouth stands where it does, and while the trade is settled in it, as it is’ This was a time when Truro was in slight decline before its rise and later construction of many fine buildings during the Georgian period. Falmouth would continue to be a dominant mercantile and port town, and of course now a university hub, whereas Truro has risen to become Cornwall’s administrative centre eclipsing the earlier capital towns of Launceston, Lostwithiel and Bodmin.

Tregony now a village was once an important trading town with historical records stretching back to Domesday. Defoe says of it ‘the chief thing that is to be said of this town, is, that it sends members to Parliament, as does also Grandpound, a market-town, and burro' about 4 miles farther up the water.’ Like many Cornish settlements that once thrived on river trade, increased mining around St Austell begun the silting up of the River Fal’s upper regions and ending Tregony’s mercantile importance along with its parliamentary franchise a century later in 1832. This was perhaps a digression of Defoe’s and from Falmouth he travelled to Penryn.

That Penryn still benefited from shipping despite Falmouth’s growing importance as a port was not lost on Defoe. He compared Penryn favourably with Truro writing; ‘yet ships come to it of as great a size, as can come to Truro itself; it is a very pleasant agreeable town, and for that reason has many merchants in it, who would perhaps otherwise live at Falmouth.’ Unlike Falmouth, a relatively new town, a settlement at Penryn was again historical enough to have been mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Trelivel’ now Treliever located on the outskirts of the town. Penryn also became significant for the location of Glasney College established by the Bishop of Exeter in 1265 and later dissolved and destroyed during the reformation. The importance of pilchard fishing was also noted, and Defoe also alluded to the destruction of Glasney with ‘it had formerly a conventual church, with a chantry, and a religious house, a cel to Kirton [Crediton in Devon], but they are all demolish'd, and scarce the ruins of them distinguishable enough to know one part from another.’

As many people will readily know Helston stands somewhat inland from Cornwall’s south coast on the small River Cober, although Charles Henderson wrote it was navigable until at least 1302. Helston is separated from the sea by land and what is Cornwall’s largest natural lake Loe Pool. Separating Loe Pool from the sea, by a matter of a couple of hundred yards, is Loe Bar which originating as a spit formed by longshore drift across what was a sunken valley thus creating the lagoon. During the visit by Defoe he noted Helston ‘stands upon the little river Cober, which however admits the sea so into its bosom as to make a tolerable good harbour for ships a little below the town’. Little evidence of Helston as a port existed, perhaps his visit coincided with one the periods occasional gaps occurred either naturally or by human intervention in Loe Bar. Helston’s status as one of the five Stannary Towns where tin was exchanged for coinage and that it ‘is large and populous, and has four spacious streets, a handsome church, and a good trade: This town also sends members to Parliament’ was recorded by Defoe in his writing.

Defoe seemingly detours to Helford the other side of the Lizard peninsula of which he is most complementary. ‘At Helford is a small, but good harbour between Falmouth and this port [Helston], where many times the TINN ships go in to load for London; also here are a good number of fishing vessels for the pilchard trade, and abundance of skilful fishermen.’ He then tells his readers of a storm that blew a tin trading ship along the coast as far as the Isle of Wight and how brave sailors, a man and two youths, saved the cargo and especially one of the lads who took the helm and courageously beached the vessel when all those ashore thought they’d be dashed to pieces. Defoe was obviously much taken by this story which would have been related to him and was pleased to confirm that ‘The merchants very well rewarded the three sailors, especially the lad that ran her into that place.’

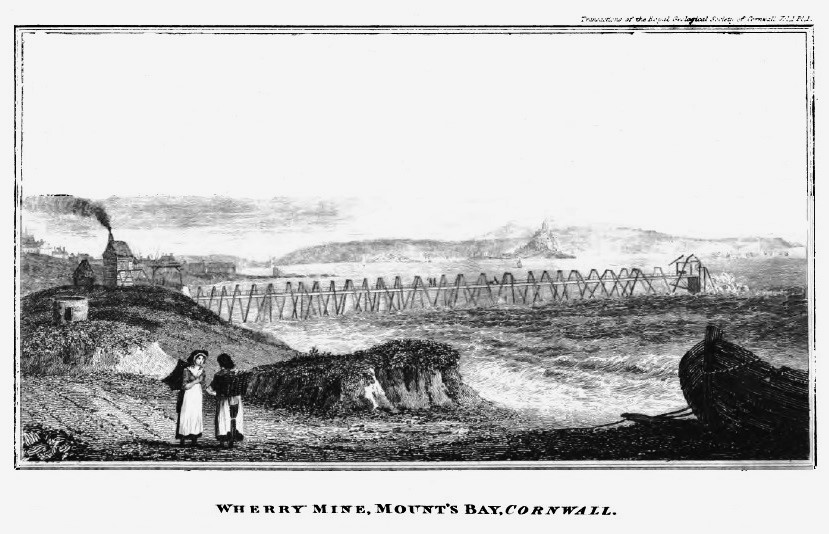

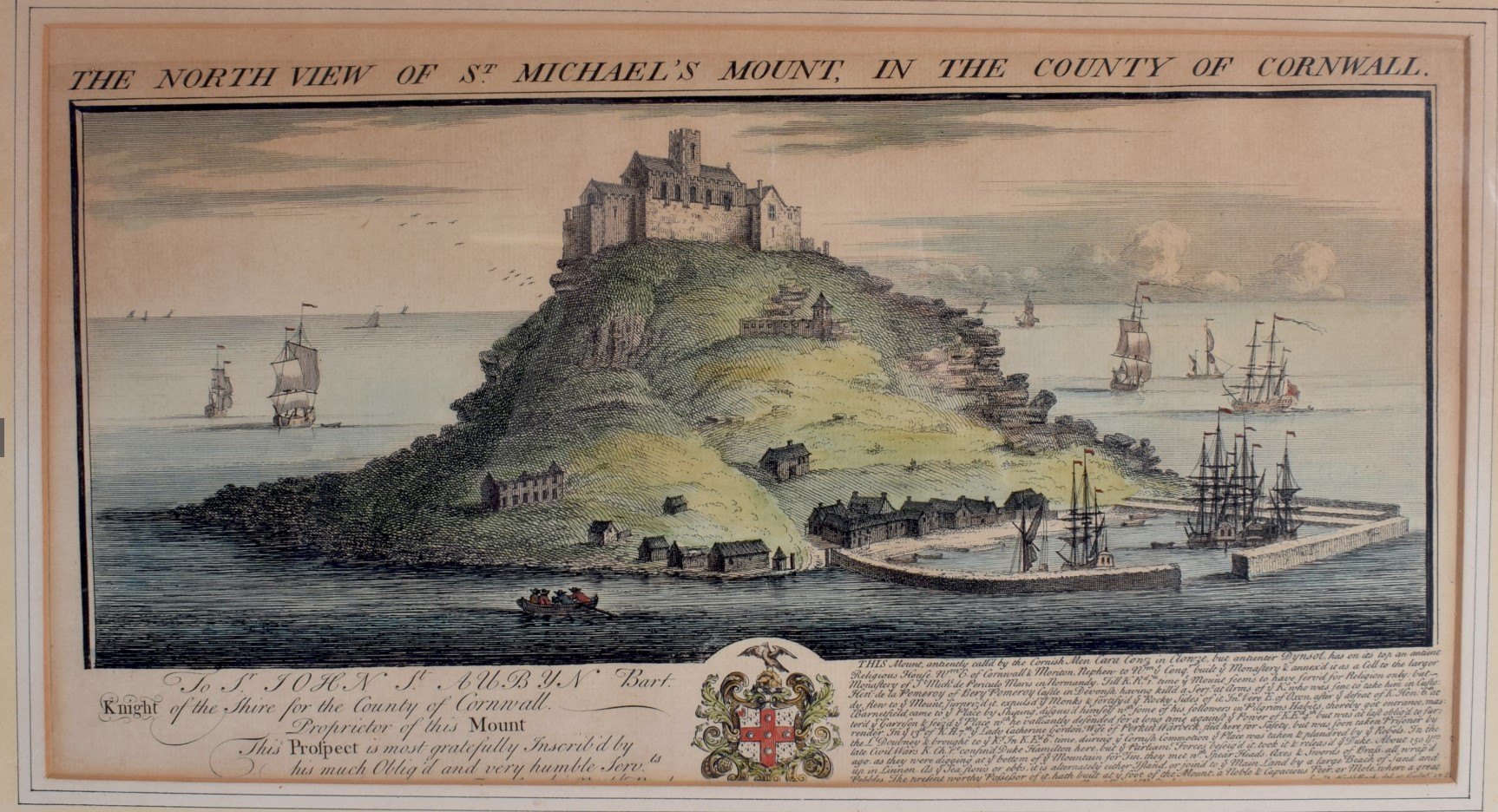

Penzance the next port of call for Defoe, although he had previously mentioned the town which we know today as Marazion, saying of it ‘a market town tho' of no resort for trade, call'd Market Jew, it lyes indeed on the sea-side, but has no harbour or safe road for shipping’. Of course later a harbour was constructed just across the water at St Michael’s Mount. The furthest west of any major town of note, Penzance is 254 miles from London and according to Defoe ‘is a place of good business, well built and populous, has a good trade, and a great many ships belonging to it, notwithstanding it is so remote. Here are also a great many good families of gentlemen, tho' in this utmost angle of the nation.’ Regarding Cornwall’s mineral wealth he writes ‘the veins of lead, tinn, and copper oar, are said to be seen, even to the utmost extent of land at low water mark, and in the very sea; so rich, so valuable a treasure is contained in these parts of Great Britain.’ Defoe’s observation regarding the veins of lead and tin in the sea are interesting. During the 18th century construction of the unusually located Wherry Mine in the bay took place, perhaps rather extravagantly described as one of the richest mines in Cornwall. However an estimated £70,000 worth of black tin was extracted in about ten years until closure in 1798. It reopened briefly in 1830 before finally closing. One other comment made by Daniel Defoe still resonates today, saying of the Cornish ‘tho' they are supposed to be so poor, because so very remote from London, which is the center of our wealth.’ It does raise questions relating to the wealth of Cornwall which has it seems benefited others far from our home.

Of course mention of Penzance and Marazion would not be complete without St Michael’s Mount. ‘Near Pensance, but open to the sea, is that gulph[gulf] they call Mounts Bay, nam'd so from a high hill standing in the water, which they call St. Michael's Mount; the seamen call it only, the Cornish Mount; It has been fortify'd, tho' the situation of it makes it so difficult of access.’ Daniel Defoe then remarks that it was once a prison for state prisoners and that it is wholly neglected. He concludes ‘there is a very good road here for shipping, which makes the town of Pensance be a place of good resort.’ Although there had been a quay at St Michael’s Mount since the 15th century it was after Defoe’s time that improvements were made to create a harbour in 1727 turning it into a flourishing seaport. The harbour was again enhanced and enlarged in 1823.

So ends this Ertach Kernow leg of Daniel Defoe’s Cornish tour and we will pick him up again after looking at other notable visitors from different centuries and how their tourist accounts described Cornwall.

![Ertach Kernow - Touring Cornwall with author Daniel Defoe [2] Touring Cornwall with author Daniel Defoe](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Ertach-Kernow-Touring-Cornwall-with-author-Daniel-Defoe-2-259x300.jpg)