Ertach Kernow - The Cornish Magazine revisited 60 years ago

The Cornish Magazine ran for about twelve years from 1958 to 1969 perhaps taking its name from the monthly magazine run by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch. This earlier incarnation of the Cornish Magazine had an even shorter lifespan from July 1898 until May 1899 containing many interesting articles. These can be found usually bound as brown coloured hardback in two volumes. From 1958 The Cornish Magazine was published by Penpol Press from their office at Ponsharden, Falmouth and edited by John Saxon. The publishers also produced a holiday guide in 1969 so were perhaps wanting to diversify. A thought was to share something from the articles of the May 1964 edition and look at what was interesting people about Cornwall during those pre-digital times sixty years ago.

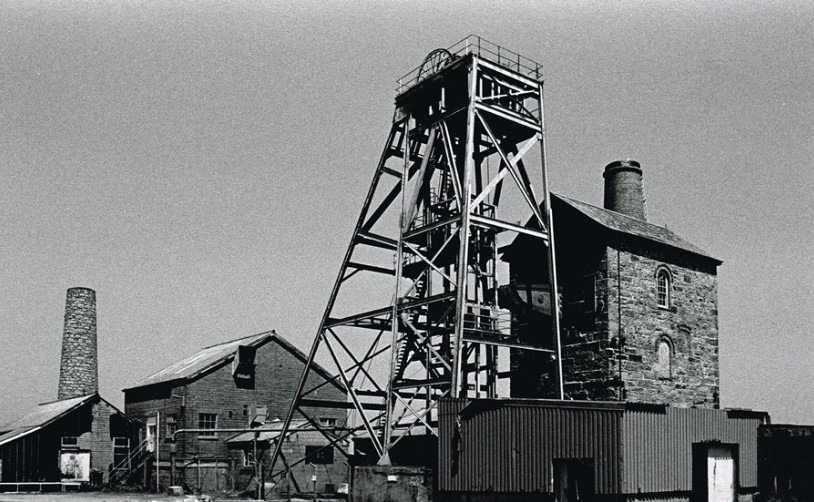

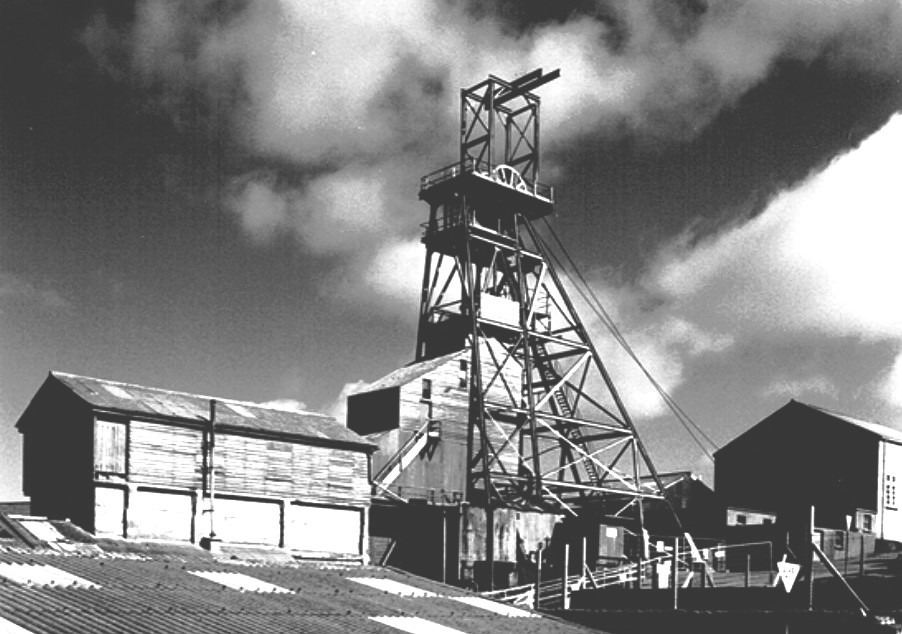

Beginning with an editorial ‘New Hopes’ there was mention of the future of tin mining ‘It now seems certain that valuable mineral deposits are still existent in Cornwall and can be extracted’. It seems that meetings were underway with a view to reopen Wheal Vor one of Cornwall’s most historic mines. However, there were so many objections and legal wrangling that Camborne Tin Limited who wanted to exploit what was considered an under extracted site abandoned the project. A substantial article entitles ‘Cornwall – An underdeveloped tin producing area’ discussed the matter of tin production in some detail. At that time only two tin mines were working Geevor Mine near Land’s End and South Crofty Mine. In 1961 the then leader of the Labour Party opposition Harold Wilson was baiting the tory government to increase tin production facilities should there be a world shortage. There was little financial incentive from the government and even a visit by Ted Heath the minister for the newly set up ‘Department for Industry, Trade and Regional Development’ failed to make changes to encourage mining investment in Cornwall. Edward Heath would later become Prime Minister and many of us remember well the problems he had with the coal mining industry elsewhere in Britain. Another major issue was the transportation of mined minerals from potential mining sites should they be resurrected. The 19th century network of mineral tramways that carried ore to smaller ports and harbours for onward transportation via ships was now virtually gone and even many of those lines existing as part of the railway network were under threat of closure. Transport would have had to be made via narrow B class roads totally unsuitable for large vehicular traffic. Despite these difficulties there were companies interested in investing in Cornish mining, but as we know now little came of it.

As always click the images for larger view

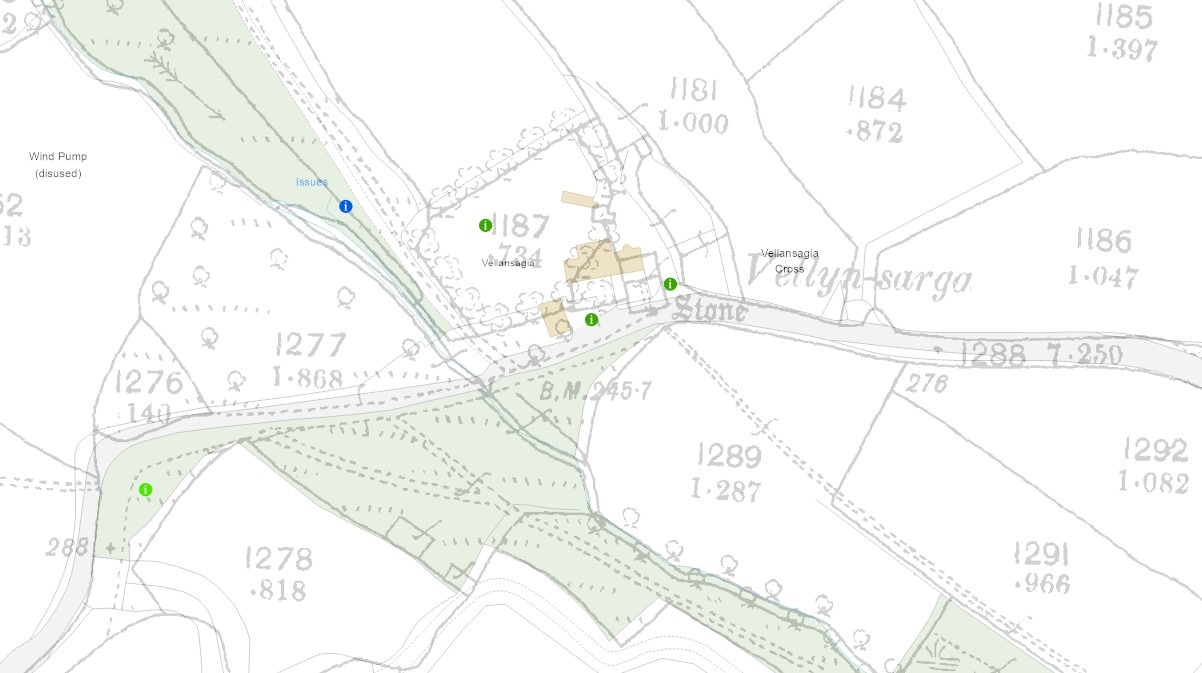

The Valley of Blood was the next Cornish Magazine article, written by Frank Ruhrmund. This related to a place called Vellansagia near to St Buryan and the article had a question as its subtitle. How did this picturesque dell come to have such a sombre name? Through it the Lamorna Cove Stream runs down to the sea and judging by the number of paintings created was obviously a very attractive view for artists. The stories of a battle in the 10th century and various other deaths there seems unlikely. Today little memory of that name or why it might have been called The Valley of Blood exists. You won’t find Vellansagia on Google maps today or much else. Investigating further than the Cornish Magazine article it seems in 1876 it was named as Vellyn-Sarga on the Ordnance Survey map and on the revised 1906 version Velansaga. There is some history as to the changing name and was first recorded in 1500 when it is spelt ‘Mellenslada’. Charles Henderson notes that there was a corn mill close by in 1680 and there is mention of a chapel by Hitchins and Drew in their History of Cornwall published in 1824 when they name it as Vellanserga. Morton Nance in his dictionary writes the elements of the name velen is often used in place names being a mutation of melen for mill, and serga/saya from sifting. So, from maybe as early as before 1500 a sifting mill may have existed there. Controversial perhaps, in the Lexicon Cornu-Britannicum dated 1865 covering the various Celtic languages the Rev Robert Williams notes that the word melen could also mean ‘of the nature of a beast, brutal, cruel’ along with the mutation velen. Perhaps back to a Valley of Blood connection after all? If you’re ever passing by look out for the medieval roadside wheel-headed cross a scheduled and Grade II listed monument.

Well-known Cornish writer and publisher Donald Rawe contributed an article to the Cornish Magazine about the life of Fredrick John Crapp a schoolmaster from St Columb. Donald describes him as a great man whose life was lived serving a small community. Born on 3rd April 1886, F J as he was known, was born to a working-class family in St Columb Major. Donald’s delightful use of words paints a wonderful picture of F J growing up in this rural farming community together with the countryside and the changing environment which gradually swept away traditional rural living and many wildlife habitats.

At an early age F J knew he wanted to become a teacher and starting out working as a pupil/teacher before getting a scholarship to London where he met his future wife Ethel Frances, marrying her in 1913. On 26th November 1915 he enlisted, joining the 6th Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry. However, he had physical deficiencies that caused his early discharge. Perhaps this was fate as he was able to continue his teaching career benefiting children in the Padstow area for thirty-three years. He was considered a good man and although strict was popular with his pupils. F J died at Newquay Hospital on May 9th 1963 aged 78. This article begun as a first anniversary tribute by Donald Rawe appeared over three editions and will bring back memories of earlier times for many older folk. A pdf will appear on the website.

Samuel Foote of Truro a man who led an interesting life during the 18th century was the topic for S Canynge Caple under the banner ‘Famous Cornishmen’. Rather an unlikely topic for a writer whose catalogue of books seems to relate entirely to cricket. Virtually forgotten, Samuel Foote was however the subject of an entry in last years Great Debate at Callywith College. Coming from a well-known and reasonably wealthy family Samuel after a failed higher education and attempt as a trainee lawyer took to the stage. His attempt at Shakespeare met with disaster on his debut night and he took to writing his own material which again led to failure and upsetting a whole raft of people through infringements of their legal rights and leading to the audience being evicted from the theatre. Obviously not one to give up a new stage production was organised meeting with great success, apart from creating ill feeling amongst the acting fraternity. Pots of money rolled in, and Foote left for Paris where he indulged himself returning in 1752 penniless, albeit with a new play. This was financially successful and in 1767 he purchased the lease and extended the Haymarket Theatre. A series of highs and lows followed, and he was swindled out of his money and taken to court by the Duchess of Kingstons chaplain on what were considered trumped up charges. He sold the patent to the theatre for an annuity of £1,600. After such a frenetic life his health suffered and in 1777 he died aged 56 at Dover on his way to France to recuperate. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

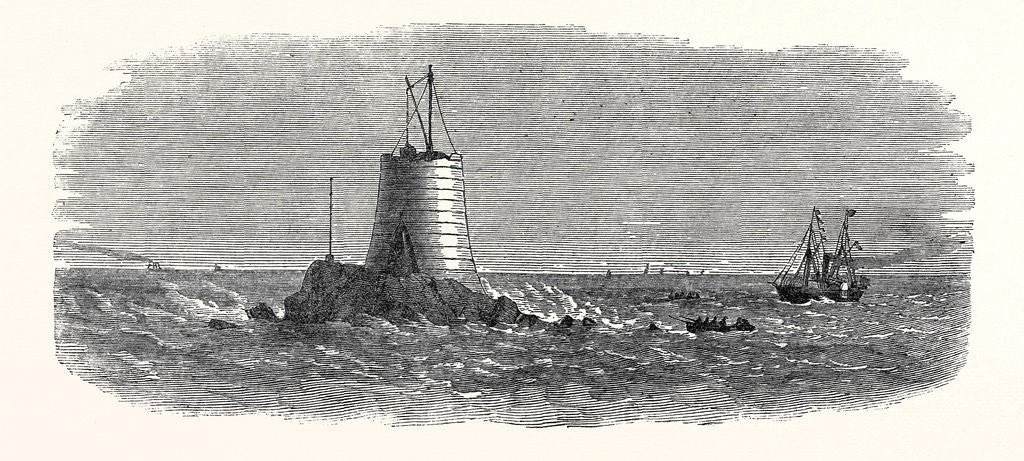

The renowned Cornish author and St Ives resident Cyril Noall wrote about the struggle to place a warning beacon on the terrible reef nine miles off Land’s End, of course the Wolf Rock lighthouse. A technical piece it’s far too long to even summarise here but there are some interesting points. How did it get its name? Well, there are a number of theories including fissures in the rocks causing a howling sound to be made when the winds blew in a certain direction. There was the hollow wolf made of copper which again was said to howl when the wind blew, thus setting off an alarm for nearby shipping. This was very soon washed away. Noall goes into detail the various attempts to create a warning on the rock, all of which failed before construction began on the current lighthouse from 1861 through to the light first shining on 1st January 1870.

That the original name Gulph Rock, mentioned in Elizabethan times is probable. The publication of ‘Great Britain's coasting pilot’ by Grenville Collins in 1693 has no mention of the name Wolf Rock only Gulf spelt alternatively Gulff and also mentioned this way in respect of the notes on the Seven Stones and Longship rocks. Collins describes it thus: ‘The Gulf is a small rock, and always above water, and Iyeth from the Landsend south-west three Leagues; this Rock is steep too on every tide and is no bigger than an ordinary Long-boat: Keep the outward part of the Long Ships on the Brizan Island, and that will carry you just on the Gulff. There is forty Fathom water within a quarter of a mile of it.’

Long before the days of Doc Martin, Port Isaac was the theme of a look at a calm and lovely village in North Cornwall. No mention of second houses but an interesting description of the village as it was sixty years ago .

Of course, the magazine had its usual share of adverts for hotels, restaurants and other Cornish businesses although not perhaps overdone like many of today’s publications. It was a most enjoyable read and a chance to reflect on what had changed over the subsequent sixty years, also providing a good excuse to carry out further research adding to some of the original stories.