Ertach Kernow - Perranzabuloe, St Piran’s three churches

St Piran besides being one of Cornwall’s historic patron saints, along with St Michael and St Petroc, will always be linked most closely with the parish of Perranzabuloe. First recorded in Domesday in 1086 the settlement within what would become the parish of Perranzabuloe was given as Sanctus Pieranus tenanted by the Canons of St Piran. It was relatively small with households of four villagers, eight smallholders and two slaves. Besides the ten acres of pasture there was eight ploughlands, an amount of land which could be ploughed by an eight-oxen plough team in the course of the year. Livestock amounted to eight cattle and thirty sheep total worth of the estate two pounds per annum, not particularly productive with an estimated value in today’s money of say £5,000.

At that time the small rough stone building we know as St Piran’s Oratory was likely still in use, probably having replaced a timber structure at some point. The Venerable Bede records during the 8th century in Northumberland that timber churches were being replaced by stone, the earliest record of this, often reusing Roman remains where they were available. No doubt the same was taking place elsewhere including Cornwall but here using local unused stone. The Oratory is thought to date from the 7th century and still in use up to the later medieval church being constructed close by. The earlier St Piran’s Oratory besides probably being inundated by sand was perhaps by that time too small for a growing, albeit dispersed population around the area. Although ecclesiastical parishes had started to be established during the ninth century throughout England and probably Cornwall this was not completed fully until the early 14th century.

As always click the images for larger view

Following it being completely covered by sand during the later medieval period the oratory would appear then disappear from time to time through the winds movement of the sands. During more modern times it was again discovered in 1835 and cleared of sand in 1843. Needless to say, rather haphazard and archeologically damaging activities were carried out on and around the oratory, including by the vicar of that time William Haslem. In 1910 a huge concrete monstrosity was erected over the oratory to supposedly protect it, which in turn was removed in 1980 and the oratory reburied. The archaeologist Dr T G Dexter who carried out work on the site was appalled by the way the building had been treated, writing in 1922; 'If the buried church could speak, she would complain bitterly of the writers who have misunderstood her, of the trippers who have robbed her, of the Church that sold her, and of the enthusiasts who have entombed her in that hideous concrete structure'.

Throughout the work at the site from 1835 onwards numerous burials were discovered. The reburial in 1980 meant the work was overseen by modern professional archaeologists carrying out work on the oratory. At this time a number of Kists, stone lined tombs, were discovered and some dated to the 8th century. This helps further confirm the early date of the site as a place of Christian worship before being mentioned in Domesday.

The second church built during the middle of 12th century is these days usually referred to as the ‘Old Church’. Now just a ruined site it stands just about half a mile from the Oratory. At that time there was a small stream running between the two church sites and that was sufficient to hold back the sand from encroaching on the new church. Around 1430 the later medieval church was extended, rebuilt in what is known as the perpendicular style the final phase of gothic medieval church building. Although little can be imagined from what is now left of this church besides the size and shape, other churches from this period throughout Cornwall give an indication. A painting from the late 18th century showing the church being engulfed by sand adds to the imagery of how it looked.

Mining in the area led to the small stream drying up or at least changing it course, thus the protection for the later medieval church from the driving sands was lost. Gradually the sands began to overcome the church, so much so that in 1704 parishioners requested permission for the church to be moved to a better and more convenient site. No doubt many residential buildings had already been inundated by the sands and people had moved further inland. The painting shows one solitary cottage already being engulfed, but smoke from the chimney indicates a hardy soul still able to dig their way in and out after storms blocked their entrance. As was the case with the church and records indicate that towards the end of the 18th century this was a common occurrence for parishioners wanting to worship there. The request to move the church in 1704 was declined as John Hosken the Vicar advised the Dean and Chapter of Exeter that this was not necessary, and any remedial work could be done for as little as £2 against a far more substantial amount to rebuild the church elsewhere. Needless to say, the church authorities took the vicars advice. Dr William Borlase visiting before 1755 wrote of the church it ‘being in no little danger the sands spreading all around it’. Mention has been made of the half buried solitary cottage a short distance away from the church which itself was surrounded by the churchyard cemetery. It reached a stage where the inevitable move was needed, not just from the issue of the moving sands, but also for convenience of those that worshipped there who now lived some distance away. The medieval church was gradually dismantled, and a new church built near the hamlet of Lambourne some three miles inland, completed in 1804, and giving rise to the settlement of Perranzabuloe there. Some burials continued at the old church right up until 1835 even after the new church was consecrated. Nothing of the old churchyard remains the painting of that time showing isolated memorial headstones. The shifting sands, especially after storms, led to graves being uncovered and human bones lying on the surface often collected by Victorian trophy hunters as a macabre pastime.

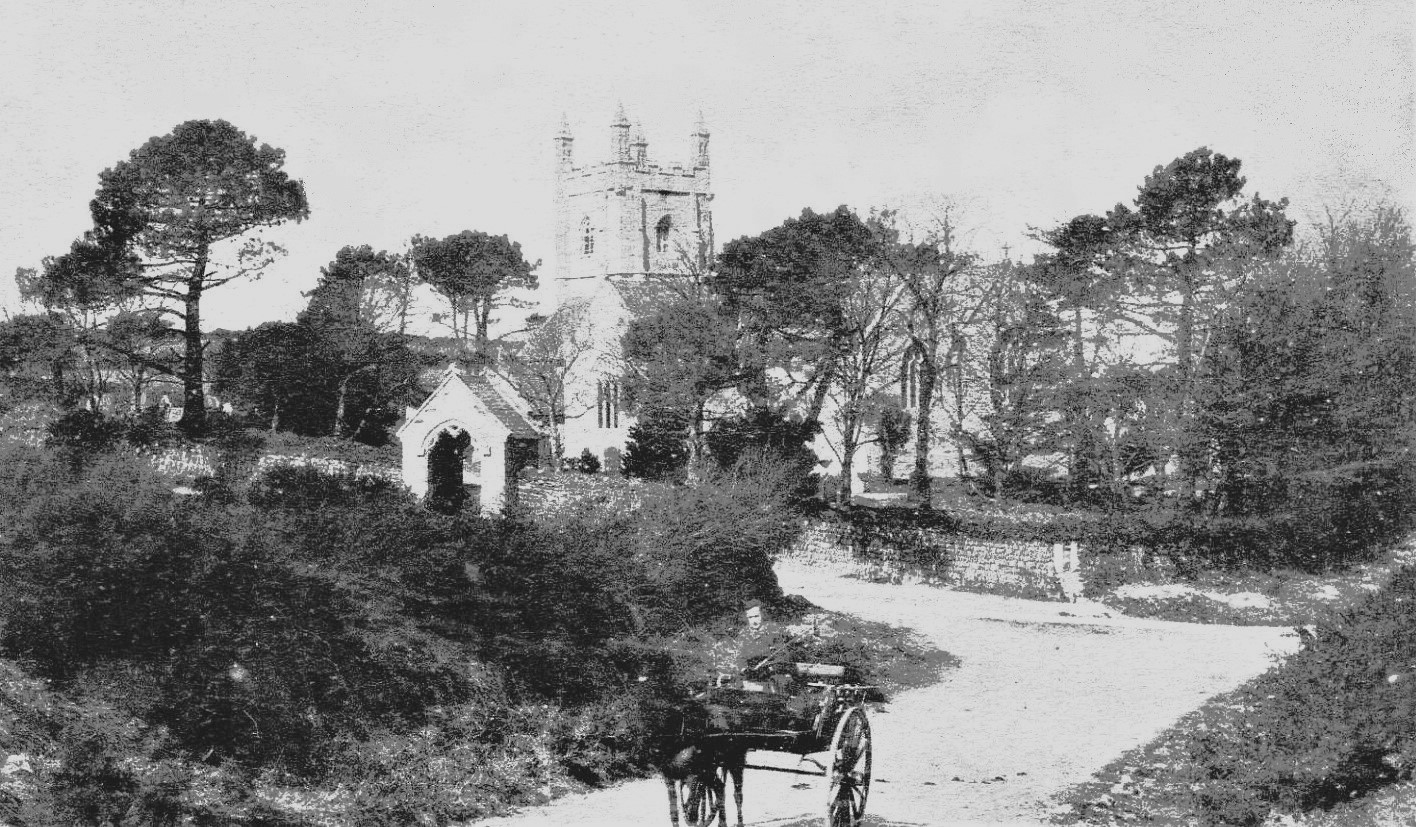

Although consecrated in 1805 the current parish church looks far older than it really is, perhaps as a consequence of much of the stone being reused from the medieval ‘Old Church’ including many carved and shaped pieces. Pevsner in his book on buildings, Cornwall edition, notes that during the 1873 restoration it was ‘made more medieval’. Sadly, the Victorians in their restoring enthusiasm actually caused much damage to historic churches as well as this one, less than seventy years old. The tower is a third lower than the original medieval building, stone perhaps used in construction of the main body of the new church.

The font in the church is possibly the oldest item on this site. In his book on Perranzabuloe published in 1836 the Reverend Charles Trelawny Collins makes reference to the font and includes a drawing. This is likely all or part of an early Norman font, but often described as 15th century. Writing about the original oratory Collins says ‘The Church, originally, contained also a vary curious stone font, which fortunately has been preserved; having been removed before the building was irretrievably buried in the sand. This font was transferred to the second church, mentioned by Carew (1602) and Norden (c1584), and now stands in the third or present Church of Lambourne.’ As one walks towards the entrance porch a strange little carved stone face looks down on you, something brought from the old church perhaps. Other items from the medieval ‘Old Church’ includes use of the earlier bench ends to make a screen to the tower lobby at the west end, and a pulpit. The stained glass and roof are typically 19th century although there are some early memorials, a fine one dating to 1675 and a later one 1725 all brought from the medieval church. There is also another even earlier one dated 1628 which was only discovered amongst rubble during excavations at the ‘Old Church’ in 2005, now wall mounted next to the font.

Outside early 19th century memorial stones indicate that despite some burials still taking place at the ‘Old Church’ local folk were being buried and memorialised at the new church shortly after consecration. John Phillips departed his life in November 1812 and John Trelease in March 1817 are just two memorials. The church as well as the lychgate at the front entrance are Grade II listed, there are also listings for a number of chest tombs within the extensive churchyard.

This parish besides these three churches dedicated to St Piran has a great number of other historic sites. This includes holy wells, sites of former manor houses, Bronze Age burial mounds and an Iron Age round with many other prehistoric features. The medieval Perran Round also lies within Perranzabuloe parish as well as other medieval sites such as chapels and earthworks. Space has defeated sharing any further exploration here, but this is a parish well worth visiting again.

![Ertach Kernow - Celia Fiennes goodbye to Cornwall [2] Ertach Kernow - Celia Fiennes goodbye to Cornwall](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ertach-Kernow-Celia-Fiennes-goodbye-to-Cornwall-2-259x300.jpg)

![[191] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 21st February 2024 - Trevor Smitheram, Cornish art and collectables Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 21st February 2024 - Trevor Smitheram, Cornish art and collectables](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/191-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-21st-February-2024-Trevor-Smitheram-Cornish-art-and-collectables-282x300.jpg)