Ertach Kernow - Padstow Haven and the infamous Doom Bar

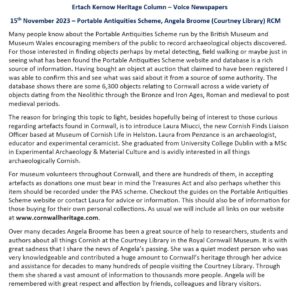

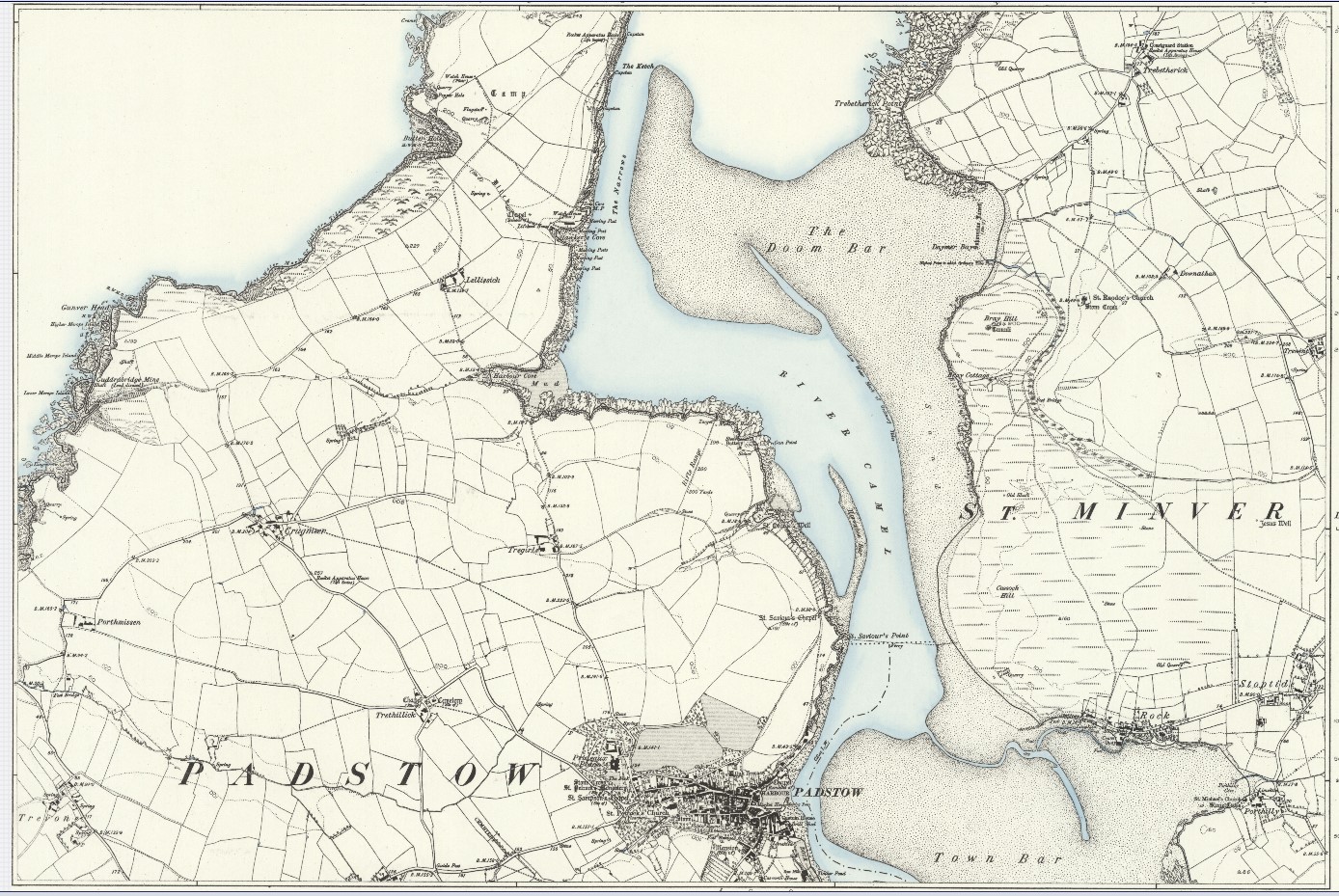

On the maps and aerial image note the changing position of the Doom Bar over a number of years

Amongst the most important of the ports on the north Cornish coast is Padstow, which has been a place for shipping for centuries. With the River Camel stretching far inland Wadebridge also became a port and still maintains boatyard interests today. Wadebridge is the lowest crossing point of the River Camel and until 1993 the historic medieval bridge was the only crossing. The importance of Wadebridge as a port was emphasised by the completion of the Bodmin to Wadebridge Railway in 1834. One of the reasons for this was to carry what was termed manure, sea sand, from Wadebridge to the inland farms around Bodmin. Passengers were also carried on part of the line even in those early days of rail transportation. The sea sand was of course taken from what was an inexhaustible supply at the mouth of the Camel estuary where lies the infamous Doom Bar.

With the railway so close at Wadebridge there was business interest in bringing it to Padstow and expanding facilities off Padstow, what had become known as Padstow Haven. This had been recognised as the best port for shelter along the north Cornish coast for centuries. Ideas of constructing a breakwater along the Doom Bar were discussed with many arguments for and against. Given the number of wrecks and the movement of these sands this idea was quashed, and the thoughts of extending the railway to Padstow with its increased port capacity not fulfilled until 1899.

What had held Padstow back during earlier medieval times was that it didn’t face the European continent where most of the trade was carried out. However, as populations increased, and vessels became larger and more seaworthy trade across the Celtic Sea to Ireland and up the Irish sea to the ports of south Wales and the west coast of England increased. William Camden in his late 16th century book Britannia commented on Padstow; ‘The site of this towne is very commodious for traffique in Ireland, to which men may easily saile in foure and twentie houres.’ John Leland in his slightly later visit to Padstow noted the trade between Padstow and Brittany ‘a good quik fischar toun’ where many small ships from Brittany came to trade goods and buy fish’. In the early 18th century Daniel Defoe on his travels around Cornwall wrote in his a ‘A Tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain’ that ‘Padstow is a large town and stands on a very good harbour for such shipping as use that coast, that is to say, for the Irish trade.’

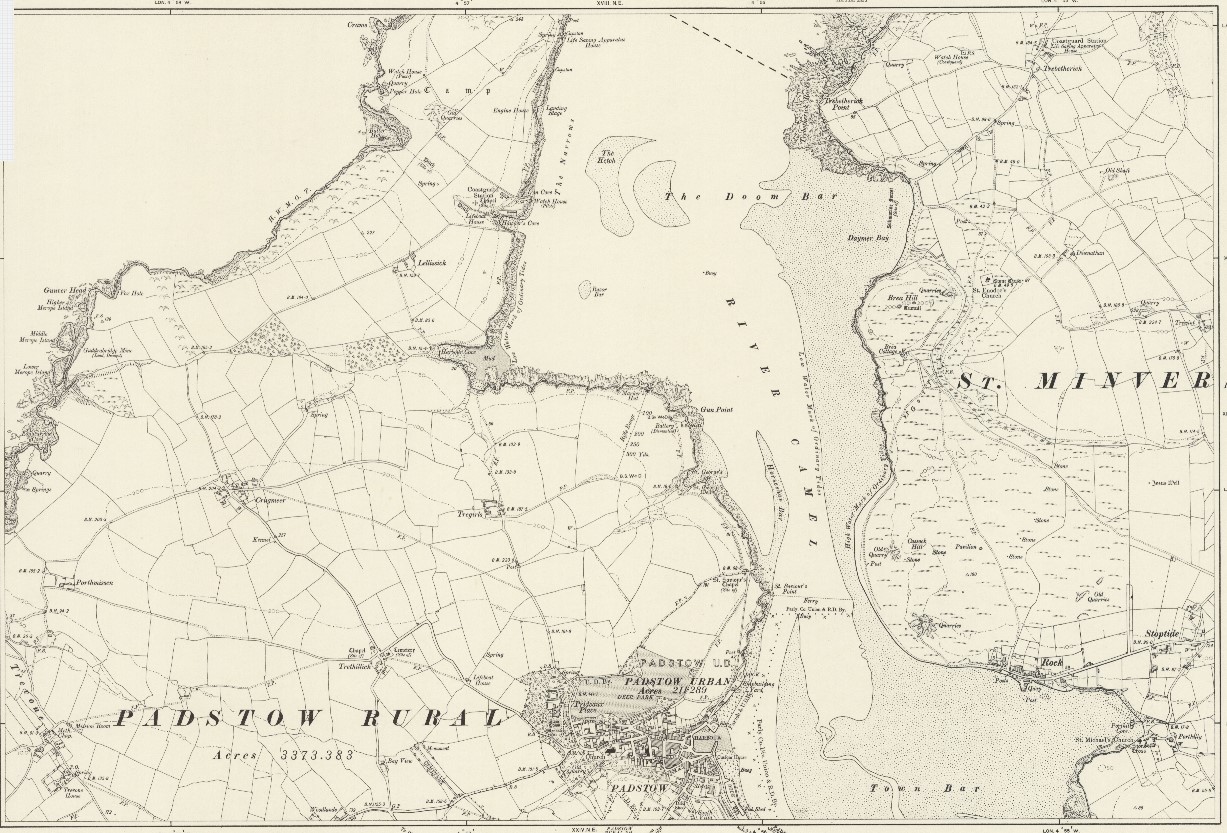

In 1579 Padstow was appointed a post town for Ireland and became the only Royal Standing Post on the north Cornish coast on 12 August 1600. Sir John Stanhope, by then the Master of the Posts, was informed by the Council that ‘it is thought meet for the more speedy conveying of letters . . . that there shall be stages laid between Plymouth, Looe, St Austell, Truro and Falmouth.’ The motives of the Council were more explicitly revealed in a second letter to Stanhope on 23 October 1601 which argued that; ‘in regard of the late descent of the Spaniards in the Province of Munster, it is thought fit for the same respects to establish the like stages to Padstow in the north coast of Cornwall ... we require you to take order for the performance of the same ... as also for the entertaining of a post barque at Padstow for the like speedy conveyance of letters from time to time by sea.’ This requirement faded as the threat from Spain diminished.

It was John Norden who whilst mapping Cornwall said of the harbour, calling it Padstow haven; ‘the beste haven in the northe parte of the Shyre, being capable of manie Ships and of greate burden, beying once entered the mouth of the haven, which is not verie secure without a skilfull Pylate; beyng rockye on the weste syde and barred with the sea sand on the easte.’ What Norden was alluding to was the quality of the place for shipping once vessels had navigated the Dunbar. The entrance through the outer estuary is just over half a mile wide and dominated by this intertidal sandbank which gradually from the 18th century became known as the Doom Bar. The early 19th century first Ordnance Survey map still retains the older name Dunbar.

This bank of sand and seashells which over the centuries is continuously built and moved by tidal forces was of greatest danger during the age of sail when loss of wind as ships entered the estuary might leave them adrift to fall foul of the Doom Bar. Many efforts and enquiries were made to remedy this problem as Padstow grew into a larger more prosperous town with the harbour expanding in importance through the increase in industrial mining and shipbuilding. It is the lime in the sand containing all the seashells that made the sand so important to farmers wanting to improve their soil.

Perhaps one of the most well-known vessels to go aground of the Doom Bar was the Royal Navy vessel HMS Whiting in September 1816. The tale of how this ship’s crew struggled to get their vessel off the sandbank is lengthy, but despite all their efforts it at last it succumbed and remained there as a reminder and a danger to shipping for many years. A survey by the Royal Navy in 1830 found that the Whiting was now ‘excepting part of one of the stern timbers, she was entirely covered with sand’. The sand was exceptionally compacted meaning the hardness of the sand prevented any salvage work and the shallow depth of water meant that a diving bell could not be used. Local folk said the wrecks stern rail was visible three feet above the sand and the hull could be walked on at low spring tide between the stern and main hatchway. A recommendation was made to remove the exposed stern section as this was the main cause of obstruction but to leave the main part of the wreck as ‘The removal of the whole of the wreck we are of opinion is not practicable by any means, being so deeply embedded in the sand’. In 2010 an archaeological investigation was made to find the wreck. Altogether its estimated that over the past two hundred years or so there has been over 200 wrecks, mainly sailing vessels, within the estuary and its approaches.

Even in the days of steam vessels the Doom Bar was taking its toll. On the night of the 24th October, 1868, during a whole gale from the W.N.W., the steamer Augusta, of Bristol, went on the Doom Bar Sand. When her signals of distress were seen from the shore, the life-boat, Albert Edward, was quickly taken to the spot. With the lifeboat’s assistance, and a line sent on board the vessel by means of the Rocket Apparatus, hawsers from two capstans on shore were got out to her, prevented the vessel from falling to leeward on the sand. Although the hawsers parted several times, prompt assistance of the life-boat and other means, they were quickly reconnected and ultimately the steamer was got off and taken up to the quay in safety, without having sustained too much damage

Today the Doom Bar is not only a danger to shipping, but also people who walk across it at low tide and then get cut off. Anglers also go out onto the Doom Bar to fish, but this should only be attempted by those with good knowledge of the tides and sands. During the first half of 2015 a local fishing vessel needed to be hauled off backwards when after trying to take a short cut across the Doom Bar she went aground. More recently in May 2019 a fatality occurred when a 17-year-old girl was drowned. The Marine Accident Investigation Branch investigation found that: ‘The dangers of being near the Doom Bar in a small boat close to low water were not fully appreciated by Norma G’s owner, who had limited boating experience. The Doom Bar caused the water depth to shallow very rapidly. This caused the sea swell to abruptly shorten into large steep plunging waves, which were unnoticed by those on-board Norma G until it was too late.’ Even today with relatively modern vessels the dangers of this shifting sandflat remain, albeit the Norma G constructed in the 1970’s was not up to 21th century safety standards.

Although Wadebridge is no longer a port, the importance of Padstow as a busy fishing harbour remains. A large lifeboat is stationed at Padstow, and members of the local National Coastwatch Institution keep watch over the estuary mouth and the Doom Bar. There are 12 lookout stations around the Cornish coast, run by volunteers, with the Padstow station located at Stepper Point. For those who benefit from the many leisure activities on Cornwall’s coastal waters, perhaps a few hours a month volunteering and possibly saving life would be most welcome at these stations.

![Stepper Point Lithograph [c1830] Wreck of HMS Whiting ringed red Stepper Point Lithograph [c1830] Wreck of HMS Whiting ringed red](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Stepper-Point-Lithograph-c1830-Wreck-of-HMS-Whiting-ringed-red.jpg)

![Fishingboat aground on the Doom Bar [NCI] Fishingboat aground on the Doom Bar [NCI]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Fishingboat-aground-on-the-Doom-Bar-NCI.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - Padstow Haven & the infamous Doom Bar [1] Ertach Kernow - Padstow Haven & the infamous Doom Bar](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Ertach-Kernow-Padstow-Haven-the-infamous-Doom-Bar-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - Padstow Haven & the infamous Doom Bar [2] Ertach Kernow - Padstow Haven & the infamous Doom Bar](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Ertach-Kernow-Padstow-Haven-the-infamous-Doom-Bar-2-254x300.jpg)