Ertach Kernow - Granite at the heart of Cornwall’s Heritage

Granite is a stone that is best recognised with Cornwall just as tin and perhaps copper are the foremost metals amongst many others linked to Cornish mining. Cornwall is a peninsula that has a character markedly different from the rest of the United Kingdom. Often overlooked stone has been important in Cornwall for centuries especially from the time stone buildings began to replace earlier timber construction, especially granite. It’s not just the stone itself but the legacy of granite quarrying in its original form and decomposed as china clay along with the properties from what it is made of, together with the granite geology beneath our feet that has been and still is important today and into the future.

The geology of Cornwall has shaped its peoples history, culture and heritage from the earliest times through to the modern age. Besides the metals and minerals Cornwall has a wide range of stones suitable for building of all types made up of sedimentary igneous and metamorphic rocks. These include limestone, sandstone, slate, serpentine, soapstone and igneous rocks of which granite is the most well-known intrusive igneous rock known to most people. Cornwall is proud of its thirty thousand miles of Cornish Stone Hedges and as one travels around different areas illustrates the different types of stone used to construct these during historic times.

As always click the images for larger view

Many of our historic buildings throughout Cornwall are of granite construction used for over five thousand years. On the moorland near Bodmin the remains of circular huts and around West Penwith the small field boundaries forming those early Cornish Stone Hedges. There are the stone circles, quoits and standing stones from Neolithic times and later many early stone crosses carved and inscribed to remind us of earlier ages. During these early times before, high demand led to industrial quarrying in the 19th century it was this granite moorstone lying in the open that was readily available to use in building. The granite from various areas of Cornwall have properties that differ, relating to the colour and hardness of the stone. Granite should not be confused with other igneous rock such as elvans, which are more finely grained. Larger buildings would likely have a variety of local stones used depending on availability but many churches and medieval buildings throughout Cornwall will contain a good degree of granite. The Luxulyan Viaduct is a good example of an industrial aged granite construction built from the local course grained St Austell granite quarried from the Carbeans and Colcerrow quarries.

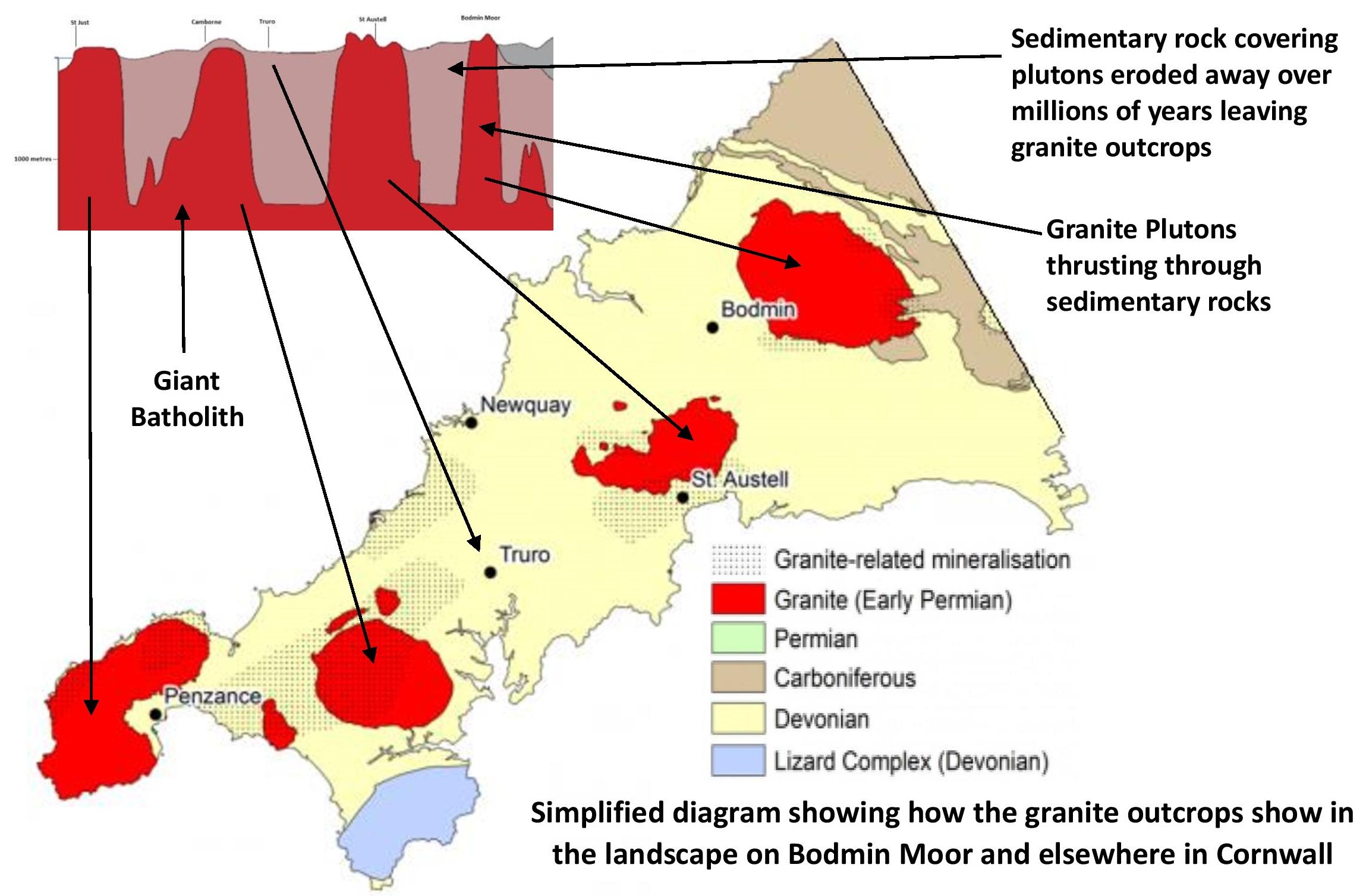

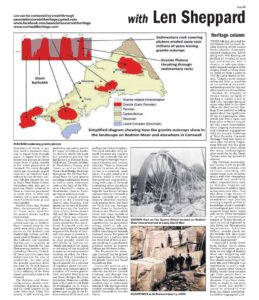

Here we mainly look at granite and Bodmin Moor which is located on one of the four major granite plutons that thrust up through the sedimentary rock to the surface in Cornwall, covering an area approaching twenty square miles. Erosion has exposed these granite intrusions making them accessible. All these bodies join up at depth of many thousand feet into one giant batholith lying at the base of Cornwall. Here in Cornwall the magma that lies even deeper never reaches the surface, where it would become known as lava, and remained cooling over millions of years forming the Cornubian granite batholith. The term batholite is used when it covers an area of greater than 40 square miles (100 square kilometres) with the Cornubian Batholite stretching from Dartmoor throughout Cornwall to the Isles of Scilly.

The last Glacial Maximum was some twenty-seven thousand years ago with an ice sheet covering Scotland, Ireland, most of Wales, and northern Britain sometimes known as the Celtic Ice Sheet. Although the area we know as Cornwall was not covered this was a time of lower sea levels with the land stretching far out into the Atlantic and joining the Anglo Celtic Isles to Europe. This enabled the ice sheet to come to within about thirty miles of Cornwall and Bodmin Moor. This created a series of periglacial landforms, a freezing and thawing effect on the fringes of the ice sheet, on the granite-based landscapes in Cornwall with perhaps the most visual results of these on Bodmin Moor. No doubt the most visually well-known of these is on Stowes Hill with the Cheesewring, but also seen on many other tors.

Lying within the granite areas of Cornwall are deposits of Kaolin better known as China Clay. This formed through a process of kaolinisation of felspar contained in the granite through decomposition of the rock by hydrothermal (hot water) action over a long period of time. Kaolin was first discovered in Cornwall by William Cookworthy in 1745 at Tregonning Hill which lies between Helston and Penzance. Compared to the four major granite plutons this is a relatively small granite area. The discovery later led to a huge expansion of a new quarrying industry that has delivered countless millions of tons of China Clay to industry in England and throughout the world for well over two hundred years.

Bodmin Moor although less well-known for its clay works these form an important part of the historic moorland landscape. Originally worked around Blisland and St Breward on a small scale before 1842 production was more widely and industrially carried out from 1860. It is believed that there have been about twenty china clay quarries working on Bodmin Moor over that time. Early power was obtained using water wheels into the 20th century using wheels such as the 50-foot Gawns Wheel, preserved in the Isle of Man. A number of larger rivers rise on Bodmin Moor including the Camel, Lynher and Fowey as well as streams many of which form tributaries into the larger rivers. Due to the abundance of water, it was later used to transport china clay in liquid form through pipes. A legacy from three former clay pits has in recent times been of great benefit to the wider population of Cornwall. The recent drought which saw Cornwall’s largest reservoir at Colliford Lake reduced to just thirteen percent full also showed the use by South West Water of these redundant clay pits put to good use. Water collected in these at Stannon purchased in 2008, Park in 2006 and Hawkes Tor in 2022 supplement Colliford Lake as and when needed.

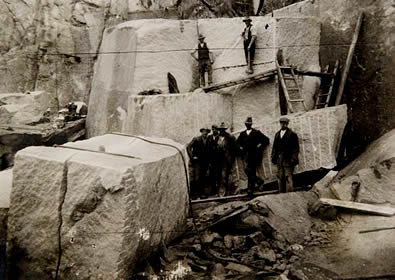

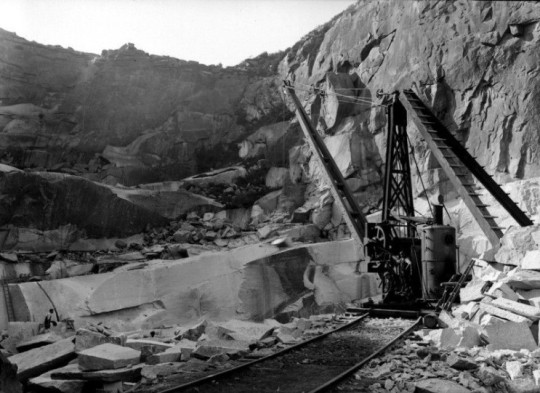

Besides china clay formed from decomposed granite there were quarries for granite blocks used in construction. There are thirty-nine recorded quarries on Bodmin Moor located towards the north-west where there was access to the Bodmin and Wadebridge railway and the south around Minions where the Liskeard and Caradon Railway ran to quarries at Kilmar Tor, Bearah Tor and Cheesewring, besides mines including Phoenix United. Of these quarries some had distinction not for size or production, but also what the granite quarried there was used for. De lank Quarry is named after the River De Lank a tributary of the River Camel and located near to St Breward. The Bodmin and Wadebridge railway records transportation of granite in 1835 and De Lank Granite Co by name from 1856. Today this quarry is still working and producing top quality granite for many prestigious works. It’s history shows De Lank has produced granite for lighthouses at Bishops Rock, Eddystone, Thames bridges at Blackfriars, Putney and Tower as well as the first Severn Road Bridge. Buildings throughout the UK have benefited from De Lank granite including Buckingham Palace as well as many memorials such as the base of Sir Winston Churchill’s statue at Westminster, those in Trafalgar Square and many more.

Another famous granite quarry is the Cheeswring Quarry near Minions. This quarry can be seen at Minions Moor passing the hurlers stone circles, below Stowes Hill and the famous Cheesewring. There was concern that blasting at the quarry would destabilise this much-loved landmark and the Royal Institution of Cornwall requested the Duchy of Cornwall take steps to preserve it. Terms of the lease granted in 1845 actually stated no act should be carried out ‘which may lead to the injury or defacing of the druidical remains or natural curiosities existing on either the Cheesewring Hill or elsewhere’. Cheesewring Quarry produced granite for a number of important places and monuments with London again a recipient of Cornish granite. This included Westminster and Tower Bridges, the Great Exhibition Memorial and the base of the tomb for the Duke of Wellington in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Granite has an important part to play in the future economy of Cornwall and perhaps the United Kingdom. The giant batholite lying beneath Cornwall also contains other raw materials that are becoming increasingly important to modern 21st century industry. There is increased interest in certain tin deposits but is a relatively small return to a past industry. It is lithium, which is now most discussed and explored for, along with areas of Cornwall containing other chemicals known as radionuclides. Perhaps the best known of these radionuclides in Cornwall is Radon, certainly not a particularly beneficial chemical in its gaseous form, but there are those that are. Amongst them there is Potassium, Uranium and Thorium which decay over long periods of time releasing heat. This heat provides Cornwall with huge opportunities for geothermal energy, which is only just beginning. The Cornubian Batholite stretching out beneath Cornwall means that parts of Cornwall has a surface heat low twice that of the UK average resulting in a geothermal gradient nearly 10 degrees Celsius per kilometre hotter. This illustrated the advantage Cornwall has for ground heat generation, all thanks to the granite Cornubian Massif beneath our feet.

Cornwall’s granite core together with other metallic minerals has led the Cornish economy and through that had an immense effect on its culture. More recent industrialisation than tin and copper mining it will through newly created scientific discovery and technology benefit Cornwall far into the future.