Ertach Kernow - The Tudors and loss of Cornish Identity

The Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 that saw the defeat of Richard III and beginning of the Tudor dynasty with Henry VII. His son Henry VIII replacement of the centuries old Catholic religion in England and Cornwall, with the protestant Church of England would under him and subsequent monarchs devastate aspects of Cornish culture and its language. The later English Civil War between Parliamentary forces and the Stuart monarchy would add to the woes of Cornish families, splitting families and ending family dynasties. Although Cornwall was far from many of these tumultuous events shaping the history of England they would have serious repercussions for Cornwall and Cornish identity.

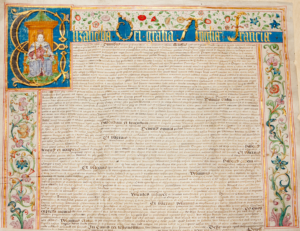

Following the Norman Conquest in 1066 much of the land was taken from the existing owners and redistributed with Robert of Mortain, half-brother to William I receiving 248 manors, these were then distributed to sub-tenants. The distance from the centre of English power games helped ensure Cornwall remained relatively isolated and unaffected through to the start of the Tudor period. There was some activity in Cornwall during what became known as the Anarchy, the civil war of the mid-12th century between Empress Matilda and Stephen of Blois following the death of Henry I. The 13th and 14th centuries saw a period of increased prosperity with earls such as Reginald de Dunstanville and Richard Earl of Cornwall issuing charters, constructing a number of high-status buildings and supporting growth in towns and trade. There were demands on coastal communities such as Looe and Fowey for naval support with vessels and sailors, or alternatively taxes for wars against France. On the whole relative seclusion ensured a peaceful existence with the Cornish language continuing in normal use amongst the ordinary working population, especially to the far west.

The late 15th century would see a change. As in England communities were split in Cornwall between the Yorkist and Lancastrians in what later became known as the War of the Roses. St Michaels Mount was placed under siege in 1473 in what was one of the earliest events involving Cornwall in the war. The beginning of the Tudor period marked the rise or sometimes return of families who had lost their lands and titles during the late Plantagenet era. However, during the turbulent Tudor monarchies many family gains from the War of the Roses were often reversed due to the religious upheavals of The English Reformation.

The Tudor period saw the Cornish language seriously compromised, unlike Wales and the Welsh language the lack of a Cornish language bible contributed to its near extinction.

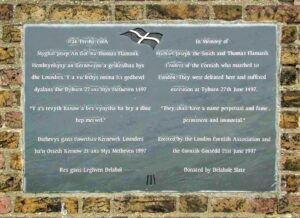

Hardship in Cornwall following tax increases by Henry VII to finance his war against Scotland led to the first Cornish uprising in June 1497. This ended with the defeat of the Cornish at Deptford and the execution of its leaders Michael Joseph ‘An Gof’ and Thomas Flamank. Another lesser-known uprising of Cornishmen followed in September that year. Continued unrest persisted in Cornwall and a second revolt was precipitated by the arrival of pretender to the English throne Perkin Warbeck at Whitesand Bay, near Land’s End. Warbeck claimed to be Richard Duke of York the younger of the Princes, allegedly murdered by Richard III in the Tower of London.

Led by Warbeck about 6,000 Cornishmen crossed the border into England and advanced to Exeter, where they stormed the city and castle. After some success they were repulsed and moved on towards Taunton with somewhat depleted numbers. By that time Henry VII was marching towards them and at that point the piteous Warbeck tried to escape but was later captured. The Cornish army surrendered to Henry who used the opportunity to raise funds by taxing Cornwall, executing a few leaders and pardoning the remainder.

Later in 1506 a Venetian ambassador commented in a letter, when held up in Carrick Roads due to bad weather; ‘We are in a very wild place which no human being ever visits’ continuing in that vein ‘in the midst of a most barbarous race, so different in language and custom from the Londoners and the rest of England that they are as unintelligible to these last as to the Venetians.’

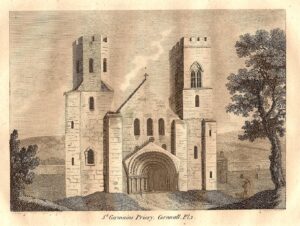

Henry VII died in 1509 and was succeeded by Henry VIII. Following Henry’s break with Rome and the establishment of the Church of England under the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Cornwall like England saw the dissolution of its monasteries and friaries. The Benedictine monastery at St Michael’s Mount fortunately survived demolition because of its strategically defensive position. The Crown kept possession of The Mount until sold by Elizabeth I towards the end of the 16th century. This was a period where many Cornish Tudor gentry benefitted from the rushed sale of church assets. F E Halliday puts it well ‘The Reformation was a social as well as an ecclesiastical revolution; by the redistribution of tithes and monastic estates the clergy were brought low and the gentry and pushing middle classes exalted’.

The Duchy of Cornwall was at that time in the hands of The Crown and Henry was still trying to produce a male heir and eliminate any potential claims to the throne. This was unfortunately for the Marquis of Exeter; he was a 1st cousin to Henry through his mother a daughter of Edward IV. As a prospective claimant he had allegations of treason levelled against him and was executed. His estate including 15 manors fell to the King and were added along with some ecclesiastic manors to the Duchy lands. This was a time that the Isles of Scilly became part of the increasingly enlarged Duchy of Cornwall estate.

Following Henry’s death, the administration of King Edward VI extended the work of relieving the church of its wealth. Collegiate buildings and land together with anything else, excepting churches were seized and sold off. There was to be no ‘Popish’ worship with all the associated paraphernalia and in January 1549 the Act of Uniformity enforced the Book of Common Prayer. Cornish people were not happy and incited by outraged people in Devon once again rose up in revolt. Needless to say, what became known as the Prayerbook Rebellion ended badly with large numbers of Cornishmen killed in battle and murdered as prisoners.

There would be no more major revolts and although there was much lively and engaging activity in Cornwall, raids by the Spanish included. By the end of the Elizabethan age in 1603 life had settled down again and people had become used to the new ways of life and a new religion. More land along the coast was brought into production for farming through the addition of sand and seaweed, mining for tin continued but was limited until the coming of industrial engineering saw it boom. Fishing remained the third major occupation and the pilchard would continue as a mainstay of the Cornish economy for a further 250 years.

Polydore Virgil an Italian cleric had been commissioned by Henry VIII to write a history of England wrote ‘The whole country of Britain is divided into four parts, whereof the one is inhabited by Englishmen, the other of Scots, the third of Welshmen, the fourth of Cornish people ... and which all differ among themselves either in tongue, either in manners, or else in laws and ordinances.’ It was accepted that Henry regarded Cornwall as a separate nation. On 23rd June 1509 in the procession preceding the following day’s coronation there were nine children riding horses representing each of Henry’s kingdoms including England, Wales, Ireland and Cornwall. In 1603, the Venetian ambassador wrote that ‘the late queen had ruled over five different 'peoples': "English, Welsh, Cornish, Scottish ... and Irish’ and references to Cornwall as a separate nation continued during the 17th century.

The Tudor period can be seen as the beginning of the slow suppression of Cornish identity by English nationalism through the diminishment of its culture. The importance of maintaining Cornwall’s identity as a nation through its language was realised early on by William Scawen (1600-1689). Professor Matthew Spriggs argues that Scawen should have greater acknowledgement as the father of the Cornish language revival. During the late 17th and 18th centuries much of Cornish culture was becoming submerged beneath a thin veneer of Englishness before slowly rising to the surface again during the late 19th and 20th centuries. During the current Queen Elizabeth’s 70-year reign, a new national fervour for Cornwall has awakened amongst the Cornish with a resurgence of pride in its culture and strengthening revival of the Cornish language. In 2012 The Crown quietly recognised Cornwall as a nation during Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth’s 2012 Jubilee celebrations, with the Baner Sen Peren being flown on the royal barge alongside those of the other four nations of the United Kingdom.

Richard III was much maligned by Tudor propaganda. Whether Cornwall and Cornish culture would have fared better had the Tudors never risen to power is something we will never know.

![[103] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 150622B The Tudors and loss of Cornish identity [S] Ertach Kernow - The Tudors and loss of Cornish identity](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/103-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-150622B-The-Tudors-and-loss-of-Cornish-identity-S-243x300.jpg)

![[103] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 15h June 2022 - Keskerdh Kernow 500 Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 15h June 2022 - Keskerdh Kernow 500](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/103-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-15h-June-2022-Keskerdh-Kernow-500-281x300.png)