Ertach Kernow - The Lanhydrock Atlas a Historic Jewel

A trip out to Lanhydrock House made me think about the Lanhydrock Atlas and what a wonderful set of maps this contained. Described by Norman J G Pounds in 1944 as of ‘quite exceptional economic and topographical interest’ these 258 maps on parchment are bound in leather in four volumes. Each sheet has a narrow ornamental border, a decorative panel containing the name of the manor or farmstead surveyed and a compass rose. Each volume covers a different area of Cornwall, volume one the extreme west with 62 maps, volume two mid-Cornwall and the Lizard with 60 maps and the final two volumes the eastern part of Cornwall with 72 and 64 maps respectively. Compiled in 1696 the maps are coloured, depending on use and field names also appear. Norman Pounds was the first person to study the maps in any great depth during the early 1940’s and he attributed the work of producing the maps to George Withiel of Penryn. However subsequent research, including by Professor William Ravenhill have determined that the maps were largely by Joel Gascoyne and probably a team. Gascoyne is recognised for his important 1699 mapping work entitled ‘Map of the County of Cornwall’.

Happily, the Lanhydrock Atlas is available for those that are interested in Cornish maps, together with farming and economics of the 17th century. In 2010 Paul Holden aided by leading Cornish experts Peter Herring and Dr Oliver Padel and others produced a wonderful volume containing all the various maps with much more additional information. The downside is that it would set purchasers back about £120, although many would still consider this well worthwhile buying.

Before looking at the wider estate as illustrated in the Lanhydrock Atlas, perhaps firstly an overview of the early estate builders and families occupying Lanhydrock House. So, who was this family to whom Cornwall owes thanks for this historic architectural jewel? The Robartes family who would become associated with Lanhydrock had relatively humble beginnings as merchants in Truro. Richard Roberts, as the family was then known, was a bailiff and timber trader who made sufficient money to acquire land and build what became known as the Great House in Truro. On his death in 1593 he passed to his son John the comfortable sum of £5,000 (approximately £1.2 million today). John obviously an astute businessman tuned this sum into what would have then been a fortune leaving his son Richard on his death in 1615 a massive £300,000 (£54 million). With wealth came the opportunity for status Richard became Sheriff of Cornwall in 1614 and in 1616 bought himself a knighthood changing the family name to Robartes. Money continued to purchase further titles with a baronetcy in 1621, and the title of Baron of Truro in 1625. During this period of hugely improved social standing Richard purchased the estate of Lanhydrock from the Trenance family in 1620. Richard’s son John would continue enhancing the families position politically under firstly the Parliamentarian government then changing sides to become entrenched in the government of Charles II following the Restoration. His political rise would include a variety of senior positions and resulting in him being created Earl of Radnor and Viscount Bodmin in 1679. After several generations of hard work building a fortune, status and power, as often happens, a generation of wastrels emerged and much of the Robarts family accumulated wealth was squandered on self-indulgence.

On acquiring the Lanhydrock estate Sir Richard had begun building Lanhydrock House, on his death in 1634 the work would be continued by his son John. The house lies immediately adjacent to the Church of St Hydroc, from which the house and estate its name, Lan indicating a church enclosure. A chapel was originally built on the site in the 11th century, by 1299 records show there was a chapel to the Priory at Bodmin here. This was rebuilt in the 15th century and was dedicated to St Hydroc in 1478. The tower has a base which predates the existing tower, is a three-stage granite structure, and the pillars either side of the nave date to the 1450’s. There are many interesting monuments within the church relating to members of the extended Robartes family as well as one to George Carminow who died in 1599.

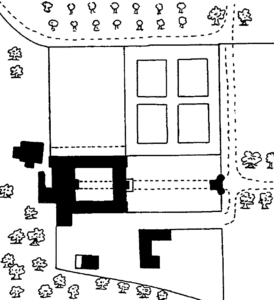

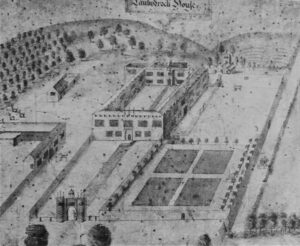

Construction of the new house was on a quadrangular plan with views over the park to the south. The gatehouse was built in 1651 by John, Richard’s son, with high walls surrounding the immediate house and gardens. The maps drawn by Joel Gascoyne are particularly useful in determining the layout of the late 17th century house, gardens and estate.

Following the inheritance of the estate by John’s son Charles Bodville Robartes, 2nd Earl of Radnor the decline of the house began. Charles was described as a scoundrel by Jonathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels) and a 'lavish curio' by the famous poet and satirist Alexander Pope. It seems he was in his day one of the most important art patrons and collectors, but this indulgence left him somewhat short of money. In turn his nephew and heir Henry Robartes, the third Earl of Radnor did nothing but squander assets of the estate on a Grand Tour before dying in Paris in 1741, leaving the estate to his sister. The house was in such a poor state that she considered sale and even demolition, but fortunately in turn passed it to her son George Hunt in 1758. With George and his heir, niece Anna Maria Agar an astute businesswoman, a revival was achieved. Her son would in turn inherit the estate in 1861 taking the name Robartes, becoming the first Lord Robartes. the Agar-Robartes family would continue as owners until 1953 when happily for Cornish folk and tourism the house was passed to the National Trust.

The quadrangle design would not last beyond 1780 when the east wing was demolished by the then owner George Hunt, which gives the present building its current shape. One hundred years later in 1881 there was a disastrous fire which almost destroyed everything but the north wing of the house, this includes the Long Gallery with its magnificent 17th century ceiling. Although this was a tragic loss of the south and west wings they were soon rebuilt and the family able to move back in by 1885. It was Thomas Charles Reginald Agar-Robartes, 2nd Baron Robartes from 1882 who carried out this work creating the wonderful building we can visit today.

The Lanhydrock Atlas illustrates the activity in the areas surrounding the house in 1696. This originally recorded a bowling green which was later laid out as a formal garden in 1857 by George Gilbert Scott. He also designed various crenelated walls surrounding the gardens. Orchards and woods are also seen on the Lanhydrock Atlas as part of the outlying park. Many changes took place during the 19th century with further changes during the 1930’s with magnolias taking the place of the walks and serpentine beds laid out in 1860, which had become very overgrown. This was seen on the early maps as the site of a 17th century walled garden.

Grounds to the west and south-west of the house were developed by the first Lord Robartes from the mid nineteenth century by enclosing the area to the west and north-west of the house separating them from the park. The Lanhydrock Atlas provides some indication that the late 17th century gardens were focussed to the north and north-east of the house, with the park running up to the stables court to the south.

The preservation and recent 2010 publication of the Lanhydrock Atlas provides a real opportunity to see Lanhydrock and its surrounds evolving from its earliest beginnings. How tastes in landscaping and the types of plantings that were in vogue during the 17th century changed. As far as the wider Robartes estates, which ultimately had upwards of 40,000 acres throughout Cornwall is concerned, the atlas gives a view of 17th century land use in many Cornish communities. Many of these will be covered over the coming months as we continue our look over Cornwall historic landscape and settlements.

![[101] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 01.06.22A Home of a historic jewel (Lanhydrock Atlas) [S] Ertach Kernow - The Lanhydrock Atlas a Historic Jewel](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/101-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-01.06.22A-Home-of-a-historic-jewel-Lanhydrock-Atlas-S-243x300.jpg)

![[101] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 01.06.22B Home of a historic jewel (Lanhydrock Atlas) [S] Ertach Kernow - Home of a historic jewel (Lanhydrock Atlas)](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/101-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-01.06.22B-Home-of-a-historic-jewel-Lanhydrock-Atlas-S-240x300.jpg)

![[101] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 1st June 2022 - Haven't we done well Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 1st June 2022 - Haven't we done well](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/101-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-1st-June-2022-Havent-we-done-well-290x300.png)