The Great County Adit - The marvel that's beneath our feet

The recent BBC series presented by Simon Reeve is considered one of the best ever produced about Cornwall and is well worth watching. It looked at a huge range of subjects within Cornwall’s various industries, past and present and included Cornish environmental, economic and social issues, as well as mentioning some wider heritage topics.

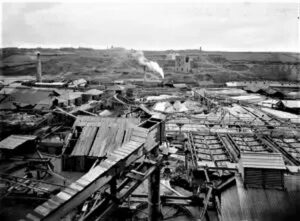

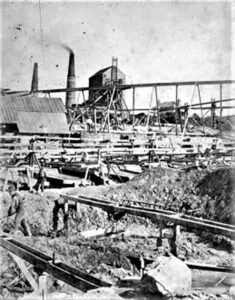

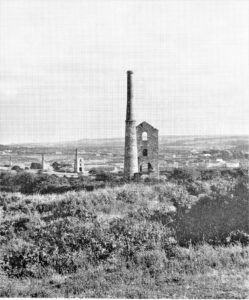

Simon’s visit to South Crofty highlighted the prospect for the restarting of Cornwall’s historic tin mining industry, primarily due to the rise of tin prices which now makes mining it here in Cornwall financially viable. Production in Cornwall would also be environmentally friendly and free from child labour exploitation seen in mining elsewhere in the world. South Crofty may have been the last operating Cornish mine but was just one of hundreds as evidenced by the engine houses from redundant mines with multiple shafts scattered around Cornwall. All of these would have had layers of galleries and adits a vast honeycomb of tunnels beneath our feet.

The merits of one particular piece of Cornish mining tunnelling has been written and praised for over two hundred years and is what has become more widely known as the ‘Great County Adit’.

The following was written in the Mining Journal in 1843. “The great Gwennap adit is the most extensive, valuable and systematic undertaking of the kind in Cornwall – perhaps in England, and we believe but few in the world exceed it in importance.”

So, what was this wonderful undertaking and what was its purpose and its achievements? Mining of all types use what are known as adits, from the Latin aditus meaning entrance. These are often far more than that and are also a source of ventilation and especially for Cornish mines drainage of water. Put simply adits are tunnelled into the main mine works at lowest levels possible and either drain water from that level or allow water being pumped up from lower levels to be passed out of the mine through the adit. This avoids the need for taking the water all the way to the surface, saving time, effort and importantly for the mine owner’s huge sums of money for coal that was required to run the pumping engines.

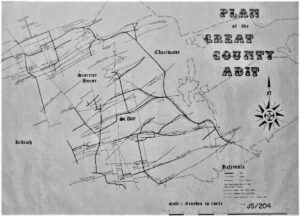

Early in the 1740’s the manager of the Poldice Mine, John Williams came up with the idea of a major adit project to drain the mine. This was backed by chief investor, or as investors were known then adventurers, William Lemon. Early water extraction was quite inefficient and costly to run and once constructed a well-engineered adit would reduce costs of water removal from the mine considerably. Poldice had become an enormous mine taking in lots of earlier mine workings and scattered over a large area. The mine had been driven ever further downwards and now the adventurers that had invested became increasingly frustrated that tin deposits at lower levels were becoming difficult to extract due to water accumulation. Taxes on coal had been reduced in 1741 and this spurred on the production and deployment of Newcomen steam engines, two of which went to the Poldice Mine. The plan was to build a 2.5mile adit that would drain the area’s shallower mine workings and to facilitate the pumping of water from lower workings. Over decades the adit gradually expanded so that numerous new spurs to other mine workings meant that it left the Gwennap area and turned north towards Chacewater and other mine workings. It became a great success not just in its operation and engineering feats, but also as a show of cooperation between mine owners and operators. In the coming decades hundreds of new engines would be purchased as the efficiency of the engineering of these improved and there was an increasing need as the amount of mining throughout Cornwall and the Poldice Mine area increased. Cornwall’s mines continued to drive even deeper to extract more tin and then increasingly copper. The adit as planned and started by John Williams proved a great investment and saved huge amounts of money by efficiently aiding the removal of water from the mines.

Ultimately by the time the final additions to what was originally called the ‘Poldice Deep Adit’, and then become known as the ‘Great County Adit’, were completed it had extended to a total of nearly 40 miles and drained water from scores of mines covering an area of over 12 square miles. The Great Adit was mentioned by numerous people in countless publications as an unbridled success well into the 20th century and talked about as a source of great pride within Cornish mining circles.

The amount of water extracted by the adit was quoted by J H Collins in his ‘Observations on the West of England Mining Region’, published in 1912, was in 1819 discharging an average of 1,250 cubic feet per minute and by 1839 this had increased to 1,627 per minute. Put in context of an Olympic sized swimming pool as we do these days that is a daily output of about 2.3 million cubic feet equivalent to 26 swimming pools. Modern belief is that it may have been far higher than that. Discharge of water from the Great County Adit is into the Carnon River and this has had the sad consequence of the river becoming highly polluted and silting up the creek at Restronguet. Even today hundreds of thousands of gallons of water gush from the Great County Adit with the water containing a multitude of minerals and causing serious environmental issues.

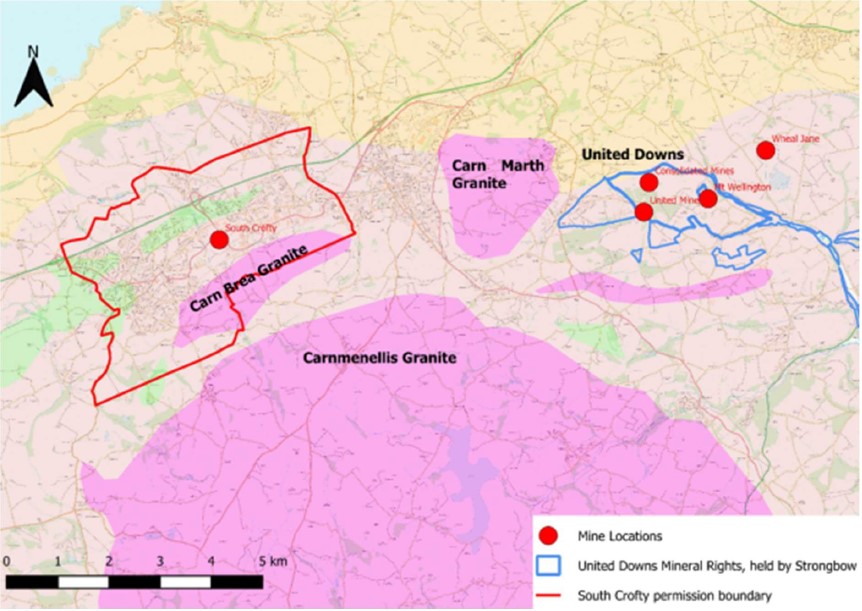

This great feat of engineering during the golden age of Cornwall’s mining history, when the Gwennap area was known as the richest square mile on earth, has come to haunt us with adverse environmental consequences. Perhaps if mining returns to Cornwall, for minerals and metals in use today such as tin, lithium and for other modern needs, the Great County Adit will again find a use and with better knowledge relating to environmental control become a 21st century asset.

Cornwall's Mining Future

Click the map image for more information about Cornish Metals

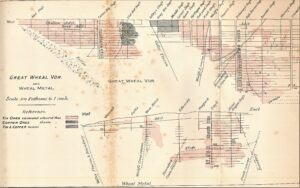

Besides the Great County Adit many thousands of miles of tunnels stretch out underneath Cornwall in multiple layers as they followed the tin and copper loads. Looking at the plans and cross sections of those mines one must consider the skill and achievements of Cornish miners in terrible working conditions. It is no wonder that Cornish miners were in such great demand beyond our shores throughout the world. As you travel around Cornwall and you see chimneys and engine houses, just take a moment to think about what might be beneath your feet.

![[22] Voice - Ertach Kernow-251120A - (Great County Adit) Marvel that's beneath our feet [S] Ertach Kernow- Marvel that's beneath our feet (Great County Adit)](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/22-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-251120A-Great-County-Adit-Marvel-thats-beneath-our-feet-S-232x300.jpg)

![[22] Voice - Ertach Kernow-251120B - (Great County Adit) Marvel that's beneath our feet [S] Ertach Kernow- Marvel that's beneath our feet (Great County Adit)](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/22-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-251120B-Great-County-Adit-Marvel-thats-beneath-our-feet-S-228x300.jpg)