Ertach Kernow - St Agnes ‘Area of outstanding natural beauty in Cornwall’

Cornwall has twelve Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), St Agnes although the smallest of these has a huge amount of content. It forms part of the Cornwall Mining World Heritage Site as well as being one of the recognised Dark Sky areas of Cornwall. Perhaps many folk have visited and not fully realised how much it has in the way of historic heritage along with the nearby village of St Agnes.

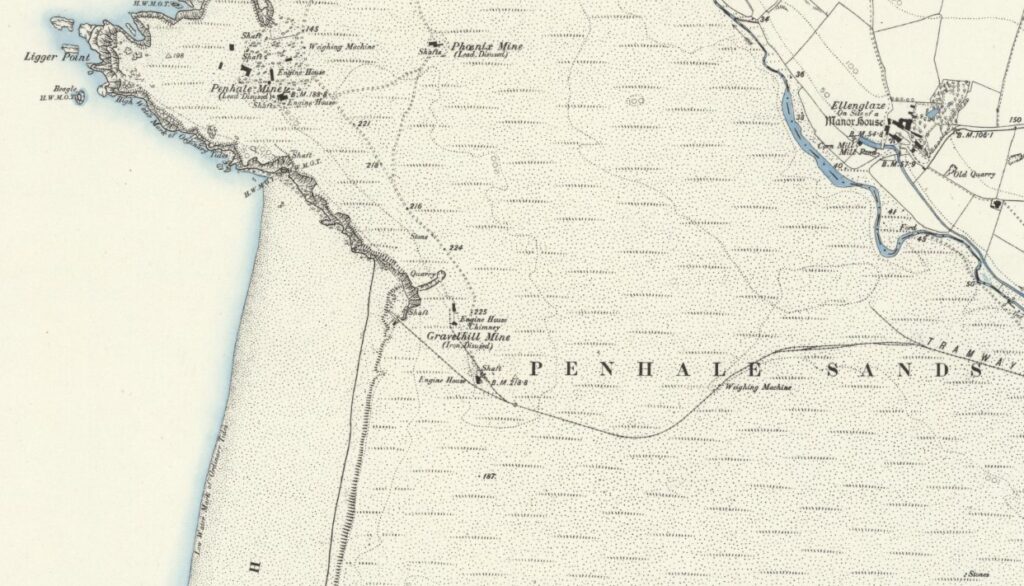

Starting off at Penhale Point this part of the Southwest Coast Path, which later passes through the St Agnes AONB, takes in a number of zones that are either Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), or Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). At Penhale Point there is an ancient cliff castle, a scheduled monument dating from the Iron Age. This has a double line of ramparts and ditches across the promontory the inner being about 2 metres high and the ditch 1.5 metres deep. The outer rampart 1metre high and a ditch nearly 1 metre deep. No doubt these would have perhaps been higher when originally constructed and the interior larger, now reduced by coastal erosion.

This area was once the site of the Wheal Golden Mine where lead was mined, along with considerable amounts of silver also being produced. The lode can be seen in the cliffs and working started here around 1777 continuing on a stop-start basis until 1873 when mining finally ended. Sadly, the fine castellated chimney stack similar in style to that surviving at Wheal Ellen, Porthtowan was destroyed along with those of the Penhale and Phoenix Mines in World War II. These were acting as a guide for bombers attacking the military base at Penhale.

Penhale Sands, which is designated a SAC and SSSI, is one of the largest dune systems in Cornwall and home to a large array of native Cornish wildlife dependant on this type of coastal landscape. However, dune landscapes are under pressure and to maintain them a project utilising manpower and equipment from the British army has helped towards restoring it. This involved removing an area of vegetation growth that had increased in recent years now allowing the wildlife that thrives in the dunes improved chances of survival. The site is also important for the preservation of various plants including Early gentian (Gentianella anglica), Shore dock (Rumex rupestris) and Petalwort (Petalophyllum ralfsii). This is the only site for two of these plants in Cornwall although Shore dock is found at one other Cornish SAC site.

Passing the former Penhale military encampment, this whole coastline is littered with various shafts and adits of redundant 18th and 19th century mines. The area is home to the ancient St Piran’s Oratory, thought to date to the 6th century and recently again uncovered. Some 350 yards away lies St Piran’s Cross understood to be the oldest Celtic cross in Cornwall along with the remains of the 11th/12th century church built to replace the lost Oratory. This was extended in 1462 and for centuries was protected from the sands by a stream, until mining caused this to dry up. The sands eventually inundated the second church, and it was closed in 1795, the last burial taking place in 1835. That there were settlements here can be judged by the positioning of the Oratory and the later Norman church with large numbers of burials surrounding them. A geophysical survey revealed remnants of nearby structures including the remains of numerous small fields. These are all now lost beneath the sand. Stonework and other infrastructure was removed from what is now known as ‘St Piran Old Church’ following its closure and used to rebuild a third church at Perranzabuloe.

What can’t be seen is the legendary lost city of Langarrow* that lies beneath the shifting sands. Robert Hunt the 19th century antiquarian and collector of Cornish in folklore takes up the story from his Popular Romances: The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall.

‘To this remote city criminals were transported from other parts of Britain. They were made to work in the mines on the coast and in constructing a new harbour in the Gannel’. He continues ‘This portion of the population of Langarrow were not allowed to dwell within the city’ Hunt describes their living, saying there is evidence for this, before telling of the downfall. ‘They were long kept widely separated but use breeds familiarity and gradually the more designing of the convicts persuaded their masters to employ them within the city. The result of this was, after a few years an amalgamation of the two classes of the population. The daughters of Langarrow were married to the criminals and crime became the familiar spirit of the place … eventually, vice was dominant and the whole population sunk in sensual pleasures. The anger of the Lord fell upon them. A storm of unusual violence arose and continued blowing without intermitting its violence for one moment, for three days and nights. In that period, the hills of blown sand extending from Crantock to Perran were formed, burying the city, its churches and its inhabitants in a common grave.’

More factual historic information about continued loss of land by residents comes from antiquary and traveller John Norden, who wrote in 1594; ‘called St Peran, now per accidens in the Cornishe Language Peran kreth; in latine Peran in Zabulo, Peran in the sande; the parish being almoste drowned with the sea sande, that the north-weste winde wherleth and driueth to the lande, in suche sorte, as the inhabitantes haue bene once alredye forced to remoue their church: And yet they are so annoyde, as they dayly loose their Lande.’

Penhale Sands then merges into Gear Sands and then Reen Sands before reaching Perranporth. Passing through the town, which has an interesting mining history, and reaching the high cliffs at Cligga Head walkers would reach the beginning of the zone of the St Agnes AONB, much of which is owned by the National Trust. Cligga Head is designated an SSSI primarily for its geology, which can be seen in the colouration of mineral and rock formations in the cliffs. As with much of this area it was heavily mined during the 18th and 19th centuries, with mine workings dotted about the landscape.

Reaching St Agnes Beacon there are wonderful views in all directions. One which may be overlooked as it is not particularly clear unless you know what you’re looking for is the ancient Bolster Bank. This was a major earthwork undertaking, probably around the late Iron Age, although not definitively dated. It is marked in the 1888 ordnance survey, surveyed in 1879, as a Roman Dike, perhaps due to a 4th century gold coin of Valentine the First being found there in 1684. During the 19th century it was known still known as Gorres perhaps as Carew suggests from Guriz, a girdle in the historic Cornish language. The Bolster Bank would have originally cut off St Agnes Head, St Agnes Beacon, and the coast between Trevaunance Cove and Chapel Porth, consisting of a single earth rampart fronted by a ditch which ran for some two miles. The best-preserved part lies south of Goonvrea, intersected by farm buildings.

St Agnes Beacon has been visited over time by a number of writers. F W L Stockdale in his Excursions through Cornwall published in 1824 says ‘The lover of the picturesque, will, however, be highly pleased to see the grandeur of the rocks, which face the shore at this point of the coast; and here is remarkably stupendous mountain, called St Agnes Beacon, rising pyramidically to the height of more than 600 feet above the level of the sea.’ Late 19th century writer J L Warden Page mentions the legend of Giant Bolster at some length but also includes interesting information about the Bank.

The much-photographed engine houses and ruins of Cornwall’s mining past at Wheal Coates creates a romantic scene, a far cry from the truth about the hardships of Cornish mining conditions. As with most mines there was earlier mining in the area before the present site was opened in 1802. Records indicate that during 1802/1803 334 tons of ore was extracted valued at £1,431 worth about £1.7 million today. Production varied and the mine had problems with extracting the water to prevent flooding from its undersea galleries and was sold in 1844. Records show that income was sporadic with the mine again being sold and then reopened in 1872. Tin production peaked through this period of operation, during 1881/1882 with an income of £10,696 (£8.2 million). Once again it closed in 1889 following three years of low production. A final attempt was made to restart mining between 1911 and 1913 but Wheal Coates finally closed in 1914. Now part of the UNESCO Cornwall Mining World Heritage Site and AONB the remaining buildings have been preserved by the National Trust and were Grade II listed in 1988.

* Langarrow has also been known as Langona, and Langorrac past names that have been used for the village of Crantoc, close to the edge of Penhale Sands.

![The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [1] The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [1]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-City-of-Langarrow-or-Lagona-by-Robert-Hunt-1-194x300.jpg)

![The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [2] The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [2]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-City-of-Langarrow-or-Lagona-by-Robert-Hunt-2-189x300.jpg)

![The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [3] The City of Langarrow or Lagona by Robert Hunt [3]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-City-of-Langarrow-or-Lagona-by-Robert-Hunt-3-300x116.jpg)

![[75] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 011221A Penhale to Wheal Coates [S] Ertach Kernow- Penhale to Wheal Coates](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/75-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-011221A-Penhale-to-Wheal-Coates-S-233x300.jpg)

![[75] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 011221B Penhale to Wheal Coates [S] Ertach Kernow- Penhale to Wheal Coates](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/75-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-011221B-Penhale-to-Wheal-Coates-S-225x300.jpg)

![[75] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 01 December 2021 - Chance to hail heritage work Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 01 December 2021 - Chance to hail heritage work](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/75-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-01-December-2021-Chance-to-hail-heritage-work-259x300.jpg)