Ertach Kernow - Sir John Betjeman, a great adopted Cornishman

Sir John Betjeman a great adopted Cornishman

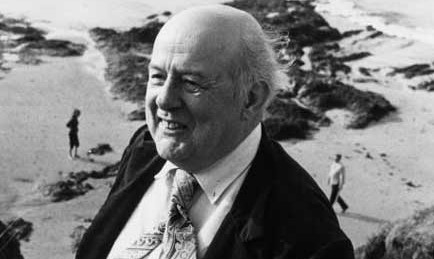

This past week I came across my 1964 edition of the Shell Guide by Sir John Betjeman, first published in 1935. This looks at a Cornwall only those of a certain age will remember from their youth. From an early age John became a great lover of Cornwall. Sir John Betjeman although born at Highgate, London in 1906 could be considered one of Cornwall’s greatest adopted Cornishmen. His contribution in helping preserve and share Cornwall’s heritage through his writing and support in safeguarding Cornish buildings and landscape must never be underestimated.

From 1908 the Betjeman family holidayed in Cornwall, beginning John’s love that would grow and bloom as he grew older. He wrote on leaving Cornwall ‘When I cross into England myself, particularly up-river over the ancient bridge at Gunnislake, I always feel like presenting my passport.’ Of his early teenage years, he recorded ‘I shall never forget that first visit (probably one of the earliest he remembered) bicycling to the inland and unvisited parts of Cornwall from my home by sea. The trees at home were few and thin, sliced and leaning away from the fierce Atlantic gales, the walls of the high Cornish hedges were made of slate. On a morning after a storm, blown yellow spume from Atlantic rollers would be trembling on inland fields. Then, as huge hill followed huge hill and I sweated as I pushed my bicycle up and heart-in-mouth went swirling down into the next valley, the hedges became higher, the lanes ran down ravines, the plant seemed lusher.’ His descriptive verses bring real life to his works in sharing an image of Cornwall.

He became a great advocate of train journeys and a steam railway enthusiast describing part of his travels in Cornwall, ‘The five miles beside broadening Camel to Padstow is the most beautiful train journey I know.’ He recounted further ‘Then the train goes fast downhill through high cuttings and a wooded valley. We round a bend and there is the flat marsh of the Camel, there are little rows of blackish-green cottages along the river at Egloshayle and we are at Wadebridge, next stop Padstow.’ I am sure that John lamented the loss of this railway line between Wadebridge and Padstow in 1967 but would have been thrilled that the old Wadebridge railway station has been preserved and repurposed. The main building of the old railway station is now The John Betjeman Centre a multi-purpose community hub.

His poem entitled Trebetherick encompasses the scenery of cliffs, sea and ancient woodland describing hedges, waves and autumn wild berries. It was here that the Betjeman family holidays began John’s strong attachment to this area of Cornwall especially. Later in 1959 Betjeman bought a house called 'Treen' in Trebetherick where he would live for the remainder of his life. The poem begins;

‘We used to picnic where the thrift

Grew deep and tufted to the edge;

We saw the yellow foam flakes drift

In trembling sponges on the ledge

Below us, till the wind would lift

Them up the cliff and o’er the hedge.’

In his book ‘Summond by Bells’ published in 1960 containing an autobiographical blank verse poem split into chapters he shares early memories from early childhood until he left Magdalen College, Oxford. Two chapters in particular relate to Cornwall, chapter IV ‘Cornwall in Childhood’ where he recounts his childhood Cornish holidays. Later in chapter VIII he describes his teenage years in ‘Cornwall in Adolescence’ a period where he really begins his exploration of Cornwall.

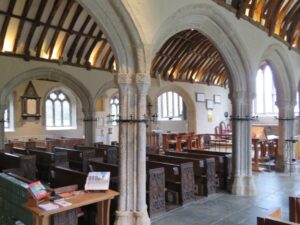

Sadly, much of what John Betjeman described is long gone, lost to Dr Beeching’s railway cuts of the 1960’s and the greed and commercialisation of Cornwall during more recent years. But some of what he loved still endures and that can be found in isolated locations and in many remaining historic listed buildings. He was very passionate about Cornish churches, of which there are many dating back to the 13th century. He wrote ‘Almost every Cornish church was rebuilt... and rebuilt in splendid style, of that hardest and most intractable material, granite. Look at it close, to see how it weathers. Look it in a quarry on Bodmin moor, and see how hard it is to work, even today. Watch how they split it. Remember all the effort when you look at the hard surface of granite. Remember how hard is to make the slightest impression. And after you’ve been watching that, look at the miracle of Cornish carving.’

An early church that John fell in love with was the parish church of St Protus & St Hyacinth of which he said ‘Of all the country churches of the west I have seen, I think that Blisland is the most beautiful. I was a boy when I first saw it thirty or more years ago.’ It was probably during his early teenage years around 1919 whilst on holiday in Trebethrick that he first visited this church. Not long after restoration it would have been bright and fresh and obviously had a great influence on Betjeman and his future love of church architecture. His affection and association with this church has allowed volunteers to raise substantial sums of money for ongoing maintenance. This includes creation at the west end of the church a ‘Betjeman Corner’.

Sir John spoke poetically of St Endellion ‘St Endellion! St Endellion! The name is like a ring of bells’ enthusing about the peal of bells ringing out across the countryside during a visit there. His depiction of the church and churchyard is so descriptive and poetic, making it far more than just an ordinary guidebook entry. Betjeman’s use of words brings the church and St Endellion alive. I wish I had read his description before my own recent visit as I’m sure I would have had far greater appreciation.

His journeys throughout Cornwall were extensive and one would need to read his Shell Guide to appreciate his travels fully. If you haven’t visited the church of St Just the Martyr, which is just a short drive away from St Mawes at St Just-in-Roseland, it is highly recommended. Not just by me, but also Sir John who says of it ‘to many people the most beautiful churchyard on earth.’ This part of Cornwall has a sub-tropical climate in which many plants flourish where elsewhere they might not, even with Cornwall’s somewhat warmer winters. What Sir John was alluding too was the peace and tranquillity enhanced by the gorgeous gardens and views over the river. The unique garden that make up the churchyard were begun in the 19th century and surround the 13th century church.

Those who know Truro for its architecture will acknowledge that the buildings in Walsingham Place, believed to have been designed by the architect Philip Sambell, make wonderful Georgian terraces. Not too long after the war these were under threat of being razed and Betjeman’s report whilst producing the Shell Guides helped prevent their loss. Truro in retaining these buildings perhaps influenced the retention of other historic structures throughout the city benefiting it architecturally. The entry for Truro in the Shell Guide is extensive and descriptive he makes a point of praising Truro in saying ‘The story of the place is still to be discerned in its buildings, for Truro has taken more care of its architecture than most cities.’ Many Cornish towns contain splendid architecture above and behind hideous 20th century signage and alterations. Sadly, much has been destroyed replaced with exotic box shaped buildings with cladding, steel and glass exteriors.

Of Newquay Betjeman follows on from 17th century Richard Carew’s critical views by writing; ‘Newquay is what all the coast of Cornwall would have been like if the speculative builders had had their way. It is unashamedly a holiday town, mostly boarding houses and big hotels and shops and is a fascinating study of the social history of England in the last century and a half. It has vitality and vulgarity.’ On Newquay’s 20th century development, ‘Then came the motor age and by now Newquay had lost its chance of becoming "smart" like St Mawes or attracting artistic people of moderate income like St Ives with its quaintness. So cheaper villas and flashier hotels arose on the outskirts of the town and over to West Newquay and East Pentire Point overlooking the Gannel and Crantock. They might just as well be in beechy Bucks or elmy Middlesex, so far as style is concerned.’ Oh dear!

Following his death in 1984 his final resting place was to be the isolated but wonderfully situated St Enodoc Chapel of which he had written a poem ‘Sunday Afternoon Service At St. Enodoc’. Surrounded by a golf course and no vehicular access it is an enjoyable walk to reach this small building that seats about 110 people. On the day I visited it was festooned with flowers following an earlier wedding and a Sunday afternoon service had just ended. There is no doubt why this place was so loved by Sir John and why he considered he would happily lie at rest there in its small peaceful churchyard.

No doubt I will be led by Sir John in my further visits around Cornwall and share his and my own views of then and now in future articles.

![St Protus and St Hyacinth Church Interior [2] St Protus and St Hyacinth Church Interior](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/St-Protus-and-St-Hyacinth-Church-Interior-2-300x225.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 07.12.2022 [A Great Adopted Cornishman -2 ]-page-001 Ertach Kernow - Sir John Betjeman, A great adopted Cornishman](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ertach-Kernow-07.12.2022-A-Great-Adopted-Cornishman-2-page-001-254x300.jpg)

![[128] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 7th December 2022 - Great Debate Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 7th December 2022 - Great Debate/ RCM AGM](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/128-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-7th-December-2022-Great-Debate-266x300.jpg)