Ertach Kernow - Sir Christopher Hawkins Boroughmonger

Sir Christopher Hawkins was mentioned in respect of Trewithen in an article on Cornish Gardens last August and that he deserved a full article for himself. One of those people who albeit famous, or perhaps to some infamous, at the time and whose name has almost been lost to the passage of time. Many people throughout Cornwall would have heard about or maybe even frequented a Hawkins Arms given establishments were established at Zelah, Pentewan, Relubus, St Hillary, Newlyn East, Cubert and Probus. Sir Christopher said he claimed to be able to ‘ride from one side of Cornwall to the other without setting a hoof on another man’s soil.’ It was due to his great landholdings that he could make this claim and why a number of public houses were named after him.

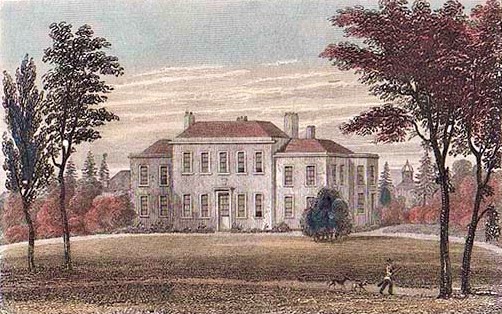

The earliest traceable Cornish ancestor was Thomas Hawkins and his wife Audrey from Mevagissey in the early 17th century. Family history being sometimes more complex than sometimes first seen. Sir Christopher’s grandfather, another Christopher Hawkins (1694-1767) of Trewinnard in St Erth, married a Mary Hawkins whose father Philip was a wealthy solicitor in Penzance. It was Philip Hawkins who had purchased the Trewithen estate in 1715 and where Christopher Hawkins was born in 1758, inheriting it and other properties including Trewinnard when his father died in 1766.

Trewinnard, now a Grade II* listed building and known as Trewinnard Manor Farm was originally the home of the historic Cornish Trewinnard family before becoming the residence of the Hawken family. Those who have visited the Royal Cornwall Museum would have seen the Trewinnard Coach which was last used to transport Mary Hawkins to St Erth Church for burial in 1780. The house now listed and protected contains a wealth of original features and this probably due to greater use by the Hawkins family of the house at Trewithen.

The famous biographer and diarist James Boswell stayed with Christopher Hawkins in 1792 and commented ‘The present representative goes on accumulating. He is said to be exceedingly rich, and he lives on a very economical plan, and very retired, though he has contrived to negotiate with Lord Falmouth for a seat in Parliament for the borough of St. Michael, and thus has been made a baronet.’ Hawkins was at the time the MP for Mitchell, known at the time as St Michael. We learn through Boswell that Hawkins regularly frequented his ancestral home at Trewinnard, St Erth and further commented that he was ‘at home in both, combining the scholarly and scientific pursuits of a Cornish landowner interested in the exploitation of mineral wealth with the greed and duplicity of an ambitious intriguer whom contemporaries learnt to describe as the Cornish borough monger’. Boswell preferred the house at Trewinnard liking its ‘air of antiquity and cultivation after the ‘bleak eminence’ of Trewithen’.

As much as people may believe todays politicians are less than transparent with hints of corruption and suchlike, they had absolutely nothing on those of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Then cash was scattered by candidates and wealthy landlords almost like confetti to buy votes. Those who’ve attended my illustrated talk ‘Dirty Rotten Borough’s’ will know of some of these wealthy culprits, which included Sir Christopher Hawkins. The corrupt parliamentary electoral system operating at that time meant that candidates could stand in and control more than one constituency, and Hawkins took full advantage of that becoming a notorious boroughmonger. This involved the buying and selling of properties across a number of pocket boroughs to benefit electoral opportunities for themselves or their nominated candidates, who would ‘look after’ the owners interests. Hawkins attended parliament as an MP for a number of seats Mitchell 1784 – 1799, Grampound 1800 – 1807, Penryn 1818 – 1820 and St Ives 1821 – 1828.

Hawkins was unfortunately for him embroiled in an electoral scandal. Following the 1806 General Election an inquiry by a parliamentary committee found Sir Christopher to be guilty of bribery and he was dispossessed of his Penryn seat. This must have been on a massive scale and besides the local election committee there was a debate in the House of Commons with a further 17 people implicated. How he was incriminated to a higher degree than any of the other boroughmongers, which included the Boscawen’s, the Earls of Falmouth, Sir Francis Basset later Lord de Dunstanville and many other well-known wealthy Cornish families is almost unbelievable. The shenanigans taking place in many Cornish boroughs is virtually beyond belief. At Tregony Mrs Allen a shopkeepers wife just happened to find £5,000 in a drawer which was then distributed to those willing to vote for a certain candidate. Huge sums of money were being used to win elections, most by foul means and Christopher Hawkins was certainly part of that.

Hawkins was not a great parliamentarian, and his attendance was said not to be at all memorable with just four speeches and those being virtually inaudible. Perhaps his interest in being a member of parliament was just to keep out those who might thwart his personal aims and goals in Cornwall. There can be no doubt that he had an urge to accumulate as much land and property as possible, adding this to already extensive holdings inherited from his father.

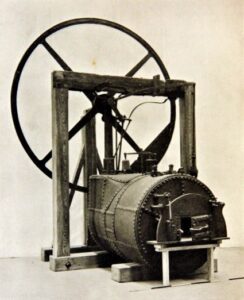

It seems that Hawkins was a forward-thinking person and in that he was a supporter of Richard Trevithick and encouraged him with his work. In 1812 Sir Christopher was the first person to adopt a high-pressure steam threshing engine for use at Trewithen. Trevithick had adapted a wrought iron boiler for agricultural purposes by attaching it to a rotating drum that separated the grain from the stalks that later became known as a threshing machine. This engine continued in use until 1879 so had a pretty good innings. It was obviously so revolutionary that a committee of experts was called in to witness it in operation and produce a report. This was very positive and concluded ‘ We approve of the steadiness and the velocity with which the machine worked, and in every respect we prefer the power of steam, as here applied, to that of horse.’ It had threshed 1500 sheaves of barley in nearly five hours with the use of one bushel of coal and sufficient steam and water still remained to finish a further 150 sheaves. Trevithick was also in negotiation with Hawkins to construct a breakwater to St Ives harbour, but the death of Hawkins ended that project.

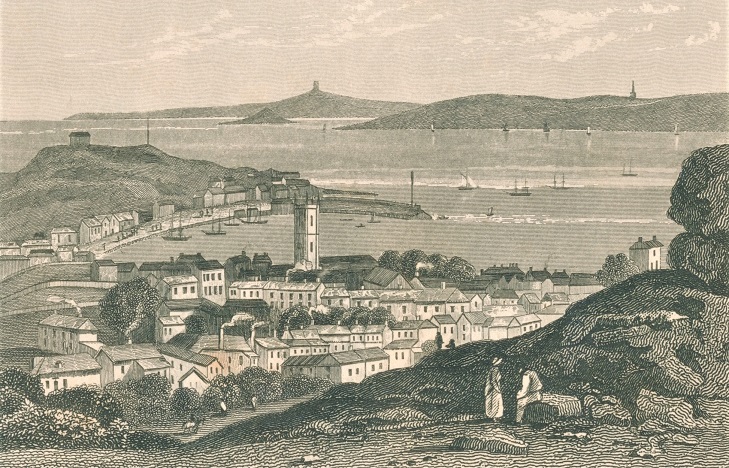

The village of Pentewan has much to thank Sir Christopher for. As the local landowner he rebuilt the harbour between 1818 and 1826 helping improve the local pilchard fishing industry. He also foresaw the growth of the china clay industry and the improved harbour helped make Pentewan a major export port for china clay, which at its peak shipped a third of Cornwall’s exports. Along with All Saints Church completed by Hawkins in 1821 a number of other buildings were constructed as part of Sir Christopher's aims to improve the village.

Sir Christopher Hawkins died on 6th April 1829 of erysipelas, a potentially serious bacterial infection affecting the skin. There doesn’t seem to be any portraits of him, rather unusual given his wealth and that there are many of other family members. Was this skin issue long standing affecting his looks or are any portraits of him lost or unacknowledged?

A note in the diary of Captain John Tregerthen Short, a well-known St Ives diarist and author of the time noted on the death of Sir Christopher; ‘Sir Christopher Hawkins, Bart., departed this life this morning in the seventy-first year of his age. His death will be greatly felt and deplored by hundreds. His charitable contributions amongst the indigent will be found greatly wanting. A more generous and benevolent landlord could not be found. He was never known to distrain for rent. He established a Free School in S. Ives for the education of the poor and gave the sum of £100 towards enlarging the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in this town.’

However, his frugal and some would say parsimonious ways did not engender positive thoughts towards him. As late as 1846 there was published in the Illustrated London News. ‘The late worthy Baronet, of Trewithen, who possessed immense estates, and great borough influence, was well known for his parsimonious habits ; and the following quaint lines, written by some facetious person on the wall of his demesne, are still remembered in Cornwall’; ‘A large house, and no cheer, A large park, and no deer, A large cellar, and no beer, Sir Christopher Hawkins lives here.’

Others considered this was not fair as hospitality was shown at Trewithen, the Cornish historian Polwhele writing; ‘Not a week before his death, I passed a delightful day with the hospitable baronet. To draw around him the few literary characters of his neighbourhood was his peculiar pleasure; and at Trewithen the clergy in particular had always a hearty welcome.’

Amusingly in 1830 following Hawkins death the Marquess of Cleveland bought Hawkins St Ives estate for £55,000. No doubt this was on the basis that it secured the purchaser control over a seat in Parliament. In 1832 with the passing of the Great Reform Act St Ives lost its franchise and ceased to be a pocket borough.

![Ertach Kernow - 15.02.2023 Sir Christopher Hawkins [1] Ertach Kernow - Sir Christopher Hawkins](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Ertach-Kernow-15.02.2023-Sir-Christopher-Hawkins-1-254x300.jpg)

![[138] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 15th February 2023 - Barbara Hepworth Exhibitions Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 15th February 2023 - Barbara Hepworth Exhibitions](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/138-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-15th-February-2023-Barbara-Hepworth-Exhibitions-298x300.jpg)