Ertach Kernow - Saviours of the Cornish language

So, what makes the five Celtic nations of the Anglo-Celtic Isles and Brittany different from England and France? Perhaps simply their different historic and cultural heritage, with a primary factor being their distinct Celtic languages. One other Celtic language, a variety of Common Brythonic, that survived both Anglo-Saxon and Norman invasions was Cumbric in the North of England. This however died out during the 12th century and recent ideas of either revival based on surviving sources or reconstruction from Late Cumbric have come to nought.

Here in Cornwall the revival of the language from the early 20th century has seen this important part of our national cultural heritage pulled back from the threat of total extinction and Cornwall increasingly asserting itself as a Celtic nation. However, it is important to remember some of the people who have gone before who had make huge contributions in maintaining records and knowledge of the Cornish language going back to the 17th century. Without their efforts the modern revivalists may have found that too much had been lost to effect a real revival as with Cumbric.

One of the earliest forerunners of the Cornish language revival was William Scawen (1600-1689). It was he who was one of the first to notice that it was gradually dying out and felt that he had to work towards its preservation. It has been suggested that it was him who had encouraged interest in the Cornish language by Edward Lhuyd and other members of the early group of revivalists. Use of the language had by Scawen’s time retreated westwards to at least St Austell and those Cornish folk living in the east of Cornwall would seldom have heard the language spoken.

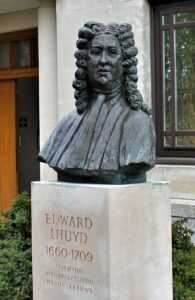

Edward Lhuyd (1660-1709) was a Welshman who after being invited by a group of Cornishmen including antiquarian John Keigwin, William Gwavas and Thomas Tonkin visited Cornwall in 1700 with the aim of helping preserve the language. This group of Cornishmen were quite aware that the Cornish language was in retreat and under threat of being lost. Lhuyd at that time was Keeper of the Ashmolian Museum in Oxford and a renowned antiquarian and linguist amongst his many accomplishments. In 1707 Lhuyd published ‘Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland’, which included important information about the Cornish language. It was Lhuyd who after much research noted the similarities through his linguistic research between the Celtic languages and really began the modern post 18th century use of the word Celtic to describe the surviving languages and their nations. The two strains of Celtic languages noted by Lhuyd were Brythonic, which includes Cornish, Welsh and Breton and the Goidelic of Scotland, Isle of Man and Ireland. Taking the Brythonic languages and the seasonal greeting ‘Happy Christmas’ the similarities can be clearly seen; Nadolig Llawen (Welsh) Nedeleg Laouen (Breton) Nadelik Lowen (Cornish).

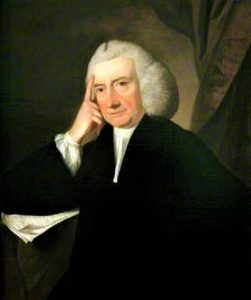

The Cornish antiquarian William Borlase as part of his interests recorded Cornish words in his 50-page dictionary, also making numerous references to the Cornish language in his ‘Antiquaries Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall‘. Borlase’s great nephew William Pryce, himself a noted antiquarian, surgeon and mineralogist collected linguistic information by questioning older folk and adding this to work carries out by Thomas Tonkin and William Gwavas. This was published as ‘Archæologia Cornu-Britannica’ in 1790. Richard Polwhele in his seven volume ‘History of Cornwall’ allocates in the final volume a section entitled ‘The Language and Literary Characters of Cornwall’ This combined the dictionaries of Borlase and Pryce, helping share and preserve the earlier works of these two men.

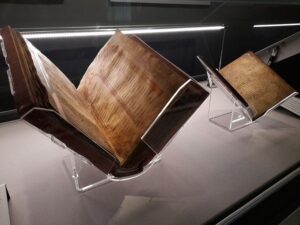

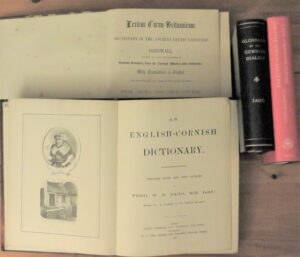

Edwin Norris who besides writing the 94-page book A Sketch of Cornish grammar, published in 1859, had also translated the three plays of the Cornish Ordinalia published in 1859 by the Oxford University Press as ‘Ancient Cornish Drama’. This translation work was subsequently occasionally ‘updated’, including much later by Robert Morton Nance. Another dictionary ‘Lexicon Cornu-Britannicum’ by Robert Williams was published in 1865. This also included examples from medieval Cornish manuscripts, with translations, as well as lexical cognates (words that have a common etymological origin) from other Celtic languages. A rather unusual contributor to the preservation of Cornish language was Louis Lucien Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon the French Emperor and General. Bonaparte amassed a considerable collection of documents by earlier Cornish antiquarians including Thomas Tonkin and William Gwavas during his research. These were deposited in the library of Bilbao by Bonaparte’s widow in 1891, but copies exist in the Courtney Library at the Royal Institution in Truro. The work of Whitley Stokes, an Irish scholar, in translating three Cornish texts between 1861 and 1872 added two thousand words to the Cornish language. Translation of ‘Gwreans an Bys’ (the Creation of the World) written by William Jordan in 1611 had however already been translated by John Keigwin in 1693. Towards the end of the 19th century Fred W P Jago a Bodmin surgeon and scholar compiled two works, a Cornish dictionary in 1887 and previously the better known ‘The Ancient Language and the Dialect of Cornwall’ in 1882.

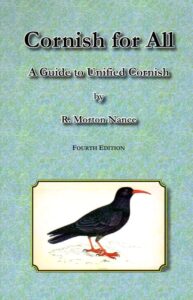

Often overlooked is A S D Smith, who perhaps better known from his Cornish language publications by his bardic name Caradar. He translated several texts and participated with Robert Morton Nance in the first Cornish-English dictionary published by the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies in 1929. The lives and work of Henry Jenner (1848-1934) and Robert Morton Nance (1873-1959) deserve to be part of later individual articles based on their input to wider Cornish and Celtic cultural heritage during the 20th century. It was they who through their endeavours and publications, supported by those such as A S D Smith, that built up an early head of steam leading them to create organisations such as the ‘Old Cornwall’ movement and Gorsedh Kernow. Nance himself published through the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies a series of dictionaries, over two hundred journal articles and many other books and booklets. Although these modern 20th century revivalists accomplished much it was also through the endeavours of those often-forgotten farsighted people through the 17th to 19th centuries who laid the foundations for their later work.

Twenty years ago, 2002 saw the Cornish language receive official recognition from the UK government. The previous year at the 2001 census the Cornish had been allocated an ethnic code, albeit the fight continues for a tick box on future census’. The recognition by the UK government of Cornish as a regional language under a European Charter along with other Celtic languages Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Scots and Ulster Scots commits them to protection of Kernewek. The granting of the Cornish minority status equal to the Irish, Scots and Welsh under the Council of Europe Framework Convention for Minorities and UK government recognition in 2014 has strengthened the cause for the Cornish language. Initiatives by Cornwall Council Language Office, Goldentree Productions, Kowethas an yeth Kernewek, Agan Tavas and other groups plus numerous Cornish speakers running language classes has improved the situation still further over the past decade. The situation regarding Cornwall’s language is more positive than it has been for centuries. There are now many more fluent Cornish speakers, several thousand who could hold brief conversations, understand or read Kernewek and many hundreds of students of all ages starting to learn each year.

Some years ago, a visit by a person, with an illustrious Cornish maiden name visited the Newquay Museum. She went on to tell me how proud she was of her Cornish ancestry and of being Cornish. When asked did she speak any Kernewek she replied, ‘why would I want to speak a dead language?’ How sad she should let her ancestral heritage down and after all Kernewek was removed from Unesco’s ‘extinct’ languages list in 2010. Fortunately, people like this are becoming a minority especially as more people increasingly use Kernewek and businesses use it as a marketing tool. The 2021 International Celtic Congress illustrated that the use of Celtic themes including the languages was a major factor in creating economic wealth throughout all our Celtic nations.

Henry Jenner considered the father of the modern Cornish revival, when asked why the Cornish should learn Kernewek replied ‘Because they are Cornish’. Perhaps we should now add that it supports Cornwall’s unique status within the family of Celtic nations and makes good economic sense.

With the New Year upon us and many of us looking for our annual attempts at a New Year’s resolution, how about injecting a few words of Cornish into our daily lives. Along with our Cornish Place Names we will occasionally be adding some words or phrases in the Cornish language box with a QR Code to scan on your mobile taking readers to audio files to help pronunciation.

![Pascon Agan Arluth [with a coloured drawing of Christ carrying the Cross] Pascon Agan Arluth [with a coloured drawing of Christ carrying the Cross]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Pascon-Agan-Arluth-with-a-coloured-drawing-of-Christ-carrying-the-Cross-228x300.jpg)

![Pascon Agan Arluth [with a coloured drawing of Christ before King Herod] Pascon Agan Arluth [with a coloured drawing of Christ before King Herod]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Pascon-Agan-Arluth-with-a-coloured-drawing-of-Christ-before-King-Herod-222x300.jpg)

![[80] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 050122A Saviours of the Cornish language [S] Saviours of the Cornish language](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/80-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-050122A-Our-Cornish-Language-S-228x300.jpg)

![[80] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 050122B Saviours of the Cornish language [S] Ertach Kernow - Saviours of the Cornish language](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/80-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-050122B-Our-Cornish-Language-S-225x300.jpg)

![[80] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 05 January 2022 - Online and physical events early 2022 Ertach Kernow Heritage Column -

Online and physical events early 2022](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/80-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-05-January-2022-Online-and-physical-events-early-2022-258x300.jpg)