Ertach Kernow - The Great 'Royal Charter Storm' of 1859 Cornish losses

Shipwrecks have always been a part of Cornwall’s relationship with the sea, due to its long coastline. Relative to its population death of mariners would have had a huge impact on the lives of those folk living in coastal communities. We have become accustomed to storms being given a name now days by the Met Office, in the past it was to remember a particular incident or characteristic of that event. So, it was with the ‘Royal Charter Storm’ that raged 25th to 26th October 1859. In recent times this might be compared to the storm of 1987 when 15 million trees were lost although loss of life was far lower.

The ‘Royal Charter Storm’ received its name from the sinking of a steam clipper that had almost reached its destination at Liverpool travelling from Melbourne, with a loss of over 450 lives. Around Britain a total 133 vessels were lost, along with heavy damage to a further 90. The Board of Trade estimated the loss of life at 800 people. The consequences of this storm was there needed to be a warning system. Although early days of weather forecasting it led to the introduction of the gale warning service in 1860 and the further development of the Meteorological Office. The Met Office was established in 1854 as a small office within the Board of Trade as a service to mariners and the maritime trade. Transportation around the coast of Britain in the mid-19th century was particularly important to Cornwall, as it relied on the coastal maritime trade through its lack of railway connections.

There appears to have been about 26 vessels lost off Cornwall due to the ‘Royal Charter Storm’, mostly off the north Cornish coast. They accounted for some 20% of the overall losses to British shipping.

On the south coast of Cornwall, the morning of the 25th started comparatively calmly. About 1.00pm the east wind increased in strength with a violent rainstorm, before veering to the North Northeast continuing unabated until 5.00pm. There was little damage to shipping at Falmouth, St Mawes or in Carrick Roads. Elsewhere in Cornwall the storm caused far more damage and death. A French bark was anchored off Porthscatho in the morning, she would have her sails mostly blown away and her chains and anchor broken. Making a run for Pendower Beach her crew of about 7 were all saved.

The smack ‘Mary Anne Jane’ from Plymouth with a cargo of coal was driven ashore against the cliffs at Porthminster Cove. Fortunately, the small crew of just two men were saved along with part of their cargo. On Hayle Bar the barque ‘Severn’ of Sunderland, laden with coal from Cardiff to Rouen, was lost. Of the crew of 11 men only one was saved. Another vessel the Rapid Mollard was stranded on the Bar but was refloated at high tide. The brigantine ‘Kate’ from Plymouth had a close escape with the help from another vessel, getting to a safe anchorage in Hayle, along with three other vessels.

Off St Agnes when the storm struck the 200-ton vessel ‘Pearl’ of Hayle was fortunate that a crew member had some local knowledge having been to St Agnes previously. Captain Jenkin ran the ship onto the beach using the light from the pier, had she gone ashore at Porthtowan it was believed she would have been lost with all of her crew. She was an old American built vessel, and the wreck was later sold.

At Perranporth three lives were lost when a sloop the ‘Mary Ann’ from Ilfracombe was driven onto the rocks at 10.00pm on the Tuesday night. With the waves sweeping her decks a crew member John Gammor was soon washed overboard and the master Richard Ridge and his two sons George and John had taken to the rigging. George the older lad supported his father and brother for a considerable time until his strength gave out, and they were washed away. The distraught survivor George was rescued at 6.00am on the Wednesday morning in great distress for the loss of this father and brother and exhaustion. A second vessel, the schooner ‘Caroline’, managed to run itself on the sandy shore and the crew were saved.

On the Wednesday morning two vessels a schooner ‘Ann’ of Penzance and ‘Anais’ a French lugger came ashore at Newquay. At that time there was no lifeboat stationed, whether that would have been able to assist at all is another matter. The crew of the Ann got ashore as the tide ebbed, those on the Anais were saved through the endeavours of the coastguard who utilised the Dennit rocket apparatus to save the men. Meanwhile just down the coast at Crantock the schooner ‘Union’ having lost her sails had been driven ashore. Once again that day the coastguard rocket brigade were in action. They were successful in saving all of the crew through sending rocket lines to the vessel. They afterwards waded into the boiling surf to help the crew ashore.

Offshore it was reported there were a number of vessels including one believed to have been an American ship with its sails totally shredded. Fear was expressed for the number of smaller colliers that plied trade between South Wales and Cornwall. The Cornish mines at this time were still very productive and their steam engines hungry for coal.

The schooner ‘Sir Robert Peel’ of St Ives, carrying coal, was wrecked at Greenbank Cove near Portreath, with the loss of all the crew of four men and a boy. The master John Richards, his son and the mate Henry Stevens bodies were recovered and buried in St Ives. The body of another crew member was also recovered later. One crew member had apparently missed the vessel leaving Swansea as he had fallen in with an acquaintance back from Australia and were drinking in celebration.

Off Padstow the schooner ‘Sultana Selina’ of St Ives was wrecked, believed to have been on the Doom Bar, the master Anthony Hart and his son being drowned. Also lost on the Doom Bar was the French Chasse-Maree ‘Providence’ and a second French vessel a brigantine the ‘Melaine’ broke up after being driven onshore. Off Stepper Point the American vessel ‘Favourite’ went to pieces after striking rocks. This may have been the vessel seen further down the coast off Hayle. Also seen from the shore was another vessel unidentified, thought to have been a brig, which foundered stern first.

Further up the north coast near Boscastle along with vessels there was terrific damage to property and trees. The ‘Happy Return’ of Padstow was abandoned by her crew and then foundered. The ‘Pet’ a smack with a local master, William Strout, carrying coal from Newport, was lost with all its crew. At Crackington Haven the schooner ‘Trio’ of Truro was lost along with the brigantine ‘Nugget’ of Newport. The crews were saved along with the cargo. ‘Sprite’ a smack based at Bideford was lost with all its crew along with most of its cargo of coal in Bude Bay.

Port Isaac saw the loss of the Newquay smack ‘Busy’. Originally a sloop it had after being sunk and recovered off Padstow in 1847, then been restored as a smack. It was carrying a cargo of coal from Newport to Pentewan. Reports say, ‘By the praiseworthy exertions of the inhabitants, in their boats, and at a great risk of their lives, with the assistance of the coast-guard, after a length of time the crew were saved’. As mentioned in a previous article this vessel had been captained by my great great grandfather 1852 to 1854 also his brother-in-law was part owner and master from time to time. This really was the end of the ‘Busy’ although the cargo was saved.

Out at sea off Trevose Head a number of other vessels were lost including the ‘Mary’ a brig from Milford, ‘Edward Protheroe (schooner) from Dartmouth, ‘Iron Age’ (brigantine) from London, ‘Richard and Elizabeth’ (smack) from Barnstaple. A further unidentified vessel was seen to sink by the lighthouse keeper on the Trevose Lighthouse.

Besides vessels lost off the Cornish coast, communities throughout Cornwall lost loved ones elsewhere. The schooner ‘Rose’ of Padstow on its return from Newport with coal and iron was caught by the storm off Baggy Point near Wollacombe, North Devon. This short piece of coast would see eight vessels lost. ‘Rose’ was crewed by four men from Newquay and only her master, William Darke would survive. The mate Michael Pollard aged 35 would have been the father-in-law of a great grandmother of mine. William, her first husband lost not only his father but his mother the previous year, leaving him just nine years old along with three siblings orphans. He in turn would drown at sea far from Cornwall in another great storm aged 30 leaving his wife with three small children. Such were the life and dangers for mariners in the 19th century.

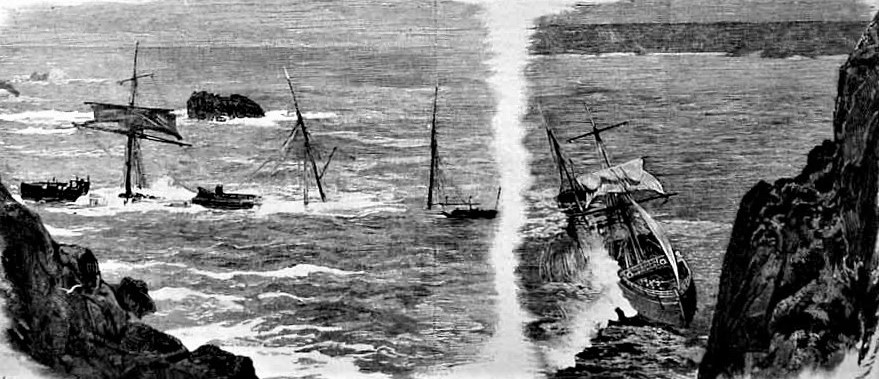

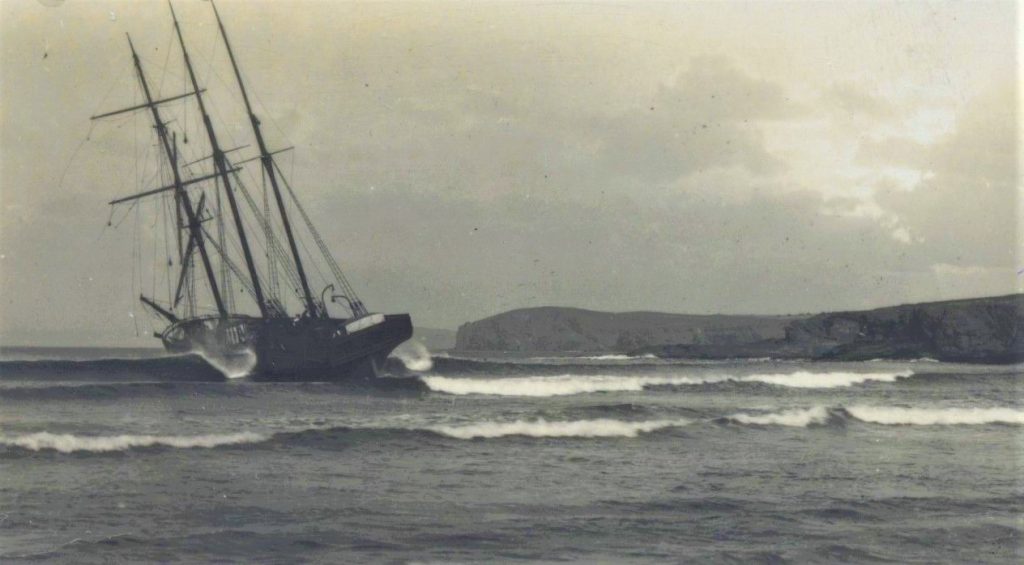

Most images do not relate to 1859 storm as nothing relating to Cornwall but provides an idea of the vessel types wrecked and how they were portrayed by artists and engravers.

![[70] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 271021A The Great Storm of 1859 [S] Ertach Kernow- The Great Storm of 1859](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/70-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-271021A-The-Great-Storm-of-1859-S-230x300.jpg)

![[70] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 271021B The Great Storm of 1859 [S] Ertach Kernow- The Great Storm of 1859](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/70-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-271021B-The-Great-Storm-of-1859-S-225x300.jpg)

![[70] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 27th October 2021 - Sharing our heritage Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 27th October 2021 - Sharing our heritage](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/70-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-27th-October-2021-Sharing-our-heritage-300x300.jpg)