Ertach Kernow - Mullion Cove Fishing, Smugglers and Wrecks

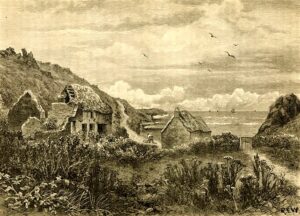

Mullion Cove is close to the village of Mullion has a history that stretches back to pre-Norman times. There is evidence of prehistoric settlement and ancient Celtic church sites within Mullion parish. Probably one of the images that has helped Mullion become better known is of its picturesque harbour, constructed from the early 1890’s. The harbour was given to the National Trust in 1945 who are now responsible for its preservation and maintenance. The harbour along with some other buildings were granted Grade II listings in 1984. Sadly, recent storms have cast doubt on the long-term future of the harbour and in 2006 a report indicated that Mullion Cove and the harbour may not stand the ongoing ravages of the sea.

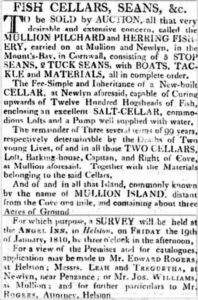

As with all Cornish coastal villages Mullion was a fishing community and this would have been primarily for pilchards. This was an important fish to the local and Cornish economy and also mentioned during Elizabethan times and before. Along with other Cornish fishing villages the number of fish caught was important news during the early part of the 19th century, even outside Cornwall. Newspaper reports gave the quantity of hogsheads caught, which were the barrels that the pilchards were put for sale once processed. A hogshead was said by author and historian Hamilton Jenkin to have held about 3,000 fish. In August 1826, the Taunton Courier reported 150 hogsheads (about 450,000 fish) were taken by two seines at Mullion. On Saturday 4th September 1830, the Royal Cornwall Gazette reported 600 hogsheads taken by the Mullion seines (about 1,800,000 fish) and they had also shot the seine nets again the following Thursday. This was serious fishing for a small community like Mullion during the heyday of the Cornish pilchard fishing industry. An auction in 1809 of fish cellars, equipment, boats, even including Mullion Island, plus new cellars at Newlyn to process the Mullion catches of up to 1,200 hogsheads, illustrates the importance and wealth of Mullion’s fishing industry during this period.

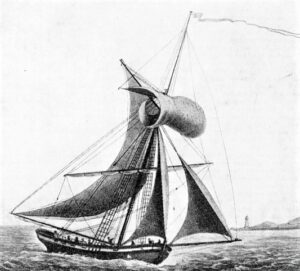

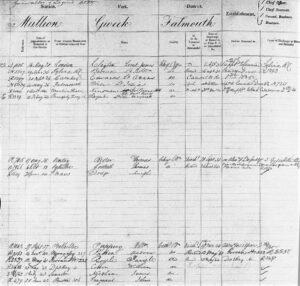

As with many out of the way places around the Cornish coast there was smuggling. This was especially rife from the early-18th well into the 19th century when large reductions in duty made smuggling unprofitable. The Waterguard was the branch that operated revenue cutters operating around the coast of Britain and the Channel Islands. These vessels needed to be fast to catch the smugglers and during the late 18th century two cutters the Hawk and the Lark operated out of Falmouth under the control of the famous Captain later Admiral Pellew. In 1786 a notorious smuggler, Thomas Welland, was caught off Mullion Island by Captain Pellow with both revenue cruisers. Welland in his well-armed 14-gun vessel the ‘Happy go Lucky’ made a run for it but was caught. Welland was killed and 12 of his 30-man crew injured. The contraband cargo of fighting cocks had escaped from their cages and were fighting each other on the deck. The size of Welland’s operation shows how profitable smuggling could be and also the dangers and risks involved.

The need for speed over the smugglers led to various government regulations including the length of vessels bowsprit and limiting the number of oars on rowing boats. The reason that our Cornish pilot gigs have just 6 oars is from when this type of vessels speed was limited, due to the need to prevent smuggling operations. Many tricks were used by smugglers hiding barrels on the seabed to be collected later, secret compartments in ships, compartmentalising barrels and many others.

Later officers with the Preventive Service would operate on shore from about 1809 helping subdue smuggling, but there were only six men to cover a large area west of Falmouth. A younger brother of my three times great grandfather was one of these men whilst my ancestor worked in the Preventive Service in Newquay. This was a dangerous job, and the smugglers were well armed and cunning.

The other great coastal activity that the preventive men needed to stop was wrecking. There seems little truth in the old stories of Cornish wreckers luring ships onto the rocks. However, that did not stop large crowds of folk gathering to see ships founder during a gale and ending up on the beach or rocks, then ready to collect and take away whatever they could of the cargo. There was also considerable effort by many folk to save the lives of the shipwrecked crew.

As trade increased in the 19th century, along with the number of vessels, so did the amount of ships being sunk and of course the coast around Mullion had its share. Between 1803 and 1874 there were 29 wrecks close to Mullion, this excludes those wrecked just over the bay around Penzance or even just a few miles up the coast where HMS Anson was wrecked off Loe Bar near Porthleven in 1807.

In 1862 rocket apparatus became available at Mullion, but of the less successful Manby model rather than the local Cornishman Henry Trengrouse design. However, this did save 30 lives up to 1874 and was provided by Mr Robartes, later Lord Robartes of Lanhydrock, who also made enquiries as to whether a lifeboat would be beneficial.

In January 1867 three wrecks in the vicinity of Mullion led to a public meeting to discuss the acquiring of a lifeboat and various other ideas to save lives. The RNLI was contacted and agreed that a lifeboat would be provided. Sadly, this came too late to save 24 people drowned when the ‘Jonkheer’ was sunk in March 1867. On 10th September 1867, the new Mullion lifeboat was launched, named the ‘Daniel J Draper’ after a Cornishman who had drowned in the Bay of Biscay. Land and a lifeboat house was provided by Mr Robartes and the RNLI carried out improvements to the bay and to landing conditions on the beach. The rocket equipment and the coastguard team continued working and saving lives for many years and the Daniel J Draper saved three lives and gave support until 1887 when she was replaced.

There are many stories regarding wrecks around Mullion and the churchyard contains many burials of crews and travellers. One mustn’t forget the tragedy of many local Mullion fishermen who also lost their lives. William Mundy and his crew of three, including his two sons and one other young man, left Mullion Cove for Porthleven on a fine morning in April 1872 to pick up some nets. There was a moderate breeze, and the sea was comparatively calm. Suddenly within a mile of Porthleven on her last tack the vessel was seen to lose way and vanish. The crew were seen beforehand, by people on shore, hurriedly taking down the sail, one man was then seen to be in the water, but nothing was found save a few belongings including a hat. William Mundy an experienced boatman was also the coxswain of the Mullion lifeboat. Over six weeks the bodies of William age 58, his son Joel 25, and friend John Williams 20 were washed up and buried in the churchyard. The body of William’s second son Henry 13 was never recovered.

A small Cornish village cove and harbour that looks so picturesque on those sunny summer days has more tales of life and tragedy than can be included here, but something to consider when visiting.

![Memorial for Henry Mundy Aged 13 [2] Memorial for Henry Mundy Aged 13](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Memorial-for-Henry-Mundy-Aged-13-2-225x300.jpeg)

![[30] Voice - Ertach Kernow-200121A - Fishing Smugglers and Wrecks - Mullion [S] Ertach Kernow - Fishing Smugglers and Wrecks - Mullion Cove](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/30-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-200121A-Fishing-Smugglers-and-Wrecks-Mullion-S-236x300.jpg)

![[30] Voice - Ertach Kernow-200121B - Fishing Smugglers and Wrecks - Mullion [S] Ertach Kernow - Fishing Smugglers and Wrecks - Mullion Cove](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/30-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-200121B-Fishing-Smugglers-and-Wrecks-Mullion-S-232x300.jpg)