Loss of HMS Anson on Loe Bar

Many Royal Navy ships have come to grief on Cornwall’s wild coastline and the loss of HMS Anson on 29th December 1807 was one that would be remembered long into the future. Cornish people have always rallied around when a ship is in the throes of being wrecked and in this case, it was mostly to save lives.

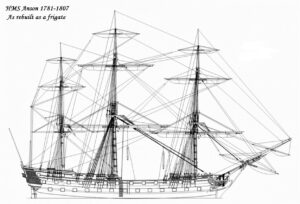

HMS Anson was a frigate of 44 guns originally put into service on 15th October 1781 as a third-rate ship of the line with 64 guns at Plymouth. The design for HMS Anson was one that was successful, based on the class lead ship HMS Intrepid’s trials in 1771, leading to further ships being built.

From early in her career HMS Anson had been in action and had fought at the Battle of the Saintes in 1782 where Admiral Rodney had defeated the French fleet and prevented the capture of Jamaica. Here HMS Anson lost her first Captain, William Blair who was sliced in two at the waist by a cannon ball.

However, experience during The Saintes battle showed she was outclassed by larger third-rate ships of 74 guns, so in 1784 HMS Anson was reduced in size by a deck and 20 guns and rebuilt and reclassified as a frigate. Her original construction meant she was able to have a main gun deck of 26 x 24 pounder cannon as opposed to frigates built as such having lighter guns of 18 pounders. She also had 2 x 42 pounder Carronades. Her heavier ship of the line construction also allowed for greater absorption of damage, thus as a frigate she was successful.

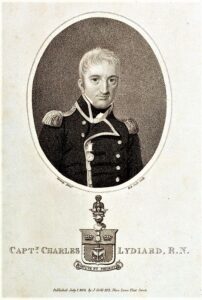

Following her conversion during the late 18th and first years of the 19th centuries HMS Anson successfully defeated and captured a number of French vessels that included frigates and Privateers. Captain Charles Lydiard was appointed to HMS Anson being her final captain. As part of a small fleet HMS Anson was part of the force that captured Curacoa in November 1806. Returning to Britain the vessel was refitted before joining the Channel Fleet, setting sail from Falmouth on 24th December 1807 to support the naval blockade at Brest.

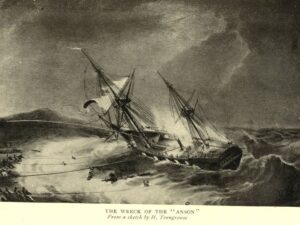

A strong storm had been developing and Captain Lydiard attempted to return to Falmouth. Issues remained with manoeuvrability and rolling due to the spars left from her early days as a ship of the line and Lydiard tried to ride the storm out by anchoring off Loe Bar. The main anchor cable snapping at 4.00am and the secondary cable at 7.00am and for Captain Lydiard the only plan was to save lives and beach the ship. He attempted to ram the shingle beach at Loe Bar, finding on impact that beneath the sand were rocks. The main mast snapped, and the vessel then broached side on to the waves. In a final attempt to anchor the vessel the emergency sheet anchor was deployed, this failed at 8.00am. Huge surf prevented boats being launched from either shore or ship to save lives although some men managed to clamber along the main mast, which had fortunately fallen towards the shore, and reach the beach, where they were helped by Cornish folk linking arms and helping them ashore.

Lydiard had stayed onboard to help affect the rescue of as many sailors as possible, he had clung to the wheel in his vain attempt to steer the ship to safer ground. It was later reported that Captain Lydiard had done everything that could be done by a brave and experienced commander, having been urged repeatedly by his officers to quit the ship, before consenting. However, he stopped to help save a small lad, probably a powder monkey, when he was washed off the mast and disappeared into the boiling seas. By 2.00pm HMS Anson was breaking up and by 3.00pm nothing remained.

What is not mentioned in modern accounts of the loss of HMS Anson was the bravery of two Methodist Preachers Mr Foxwell from Mullion and Tobias Roberts from Helston who crossed to the ship and saved many lives between them. Also, a poor labourer Alexander Matthew who crossed to the ship repeatedly saving four men and a child. It was commented that ‘this man’s actions we have no doubt will speak home to the hearts of the virtuous rich.’ There were of course some who let the side down and tried to steal some of the ship’s stores washed up. Accounts report that Tobias Roberts put in charge of these apprehended the ringleader and was said to have given him a ‘decent threshing’.

Captain Lydiard’s body was washed up and recovered on 1st January 1808 and he was initially interred at Falmouth before being reburied in the family tomb at Haselmere. He left a wife and five children including three young boys one of which in due course would join the Royal Navy and rise to the rank of Rear Admiral. The bodies of the other wreck victims were buried on the clifftop where a memorial now stands. The total numbers of deaths were unknown but somewhere between 60 and 190. Many survivors who had been pressganged into service fled and deserted once they reached shore making total losses difficult to be known accurately.

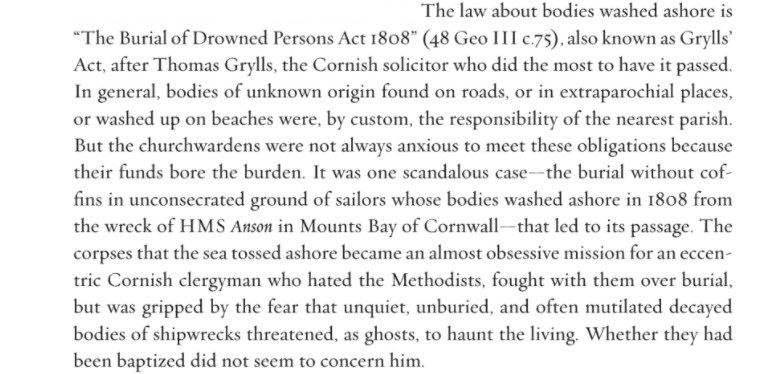

Ongoing results of this disaster were due to the action of three Cornishmen. Henry Tregrouse had witnessed this tragedy and would, due to the effect on him go on to invent lifesaving equipment. This would as a consequence result in the saving of many hundreds of lives worldwide. We will meet Henry again and do his work better justice than this brief mention. Another Cornishmen who was affected as a result of the aftermath of this sinking was Thomas Grylls a wealthy solicitor from Bosahan and Helston. This related to the treatment of the seamen that were washed up and the traditional ‘casual’ burial of such people, usually on the closest land above high water. Unfortunately, today in areas of higher coastal erosion from time to time the skeletal remains of one or more persons buried long ago in a single or mass grave are exposed. Thomas Grylls penned the wording for an act of parliament that would become known as the ‘Grylls Act’. This was introduced to Parliament by a third Cornishman, John Hearle Tremayne of Heligan one of 44 Cornish MP’s at the time. The Burial of Drowned Persons Act passed in 1808 required that those bodies washed ashore were decently interred in consecrated ground. Not always followed and often avoided to save costs the requirements were supplemented by a further act in 1886. Both the 1808 Burial of Drowned Persons Act and subsequent 1886 Act were replaced by the National Assistance Act 1948.

Well known for his work in vigorously following the requirements of the 1808 act was the vicar of Morwenstow, Rev R S Hawker. He ensured that men drowned following wrecks on the harsh North Cornwall shores around his parish were tended and buried with the greatest dignity.

Cornish folk should be proud to know that following the tragedy of the sinking of HMS Anson that Cornishmen were at the forefront of action taken that would be saving lives and ensuring bodies of wreck victims were well treated following their deaths, hopefully bringing some solace to their families.

Canon recovered from HMS Anson can be seen outside The Helston Museum and at the harbour Porthleven.

![[27] Voice - Ertach Kernow-301220A - Wreck of the Anson [S] Ertach Kernow - Wreck of the Anson](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/27-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-301220A-Wreck-of-the-Anson-S-235x300.jpg)

![[27] Voice - Ertach Kernow-301220B - Wreck of the Anson [S] Voice - Ertach Kernow - Wreck of the Anson](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/27-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-301220B-Wreck-of-the-Anson-S-229x300.jpg)