Ertach Kernow - Logan stone of Treen

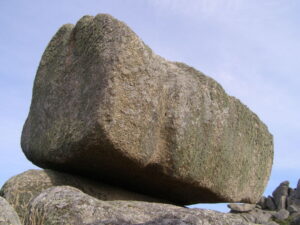

Logan stones often called logging stones are a natural phenomena which have become so finely balanced that it takes very little effort to move them. These were formed through natural causes such as glacial movement and erosion. Although not rare they are becoming increasingly so through the action of man and continued natural erosion. Cornwall has or had a number of these stones, some which fortunately still rock and others which have done so until more recent times. The rocking stone of Zennor apparently no longer rocks but was photographed in 1858 and described as ‘The Rocking Stone of Zennor’. The Logan Stone at the top of Men-Amber Rock was overthrown from its pivot by Cromwell’s troops during the English Civil War, as it was a meeting place for royal sympathisers. Fortunately, The logan rock on Louden Hill Bodmin Moor is one that still rocks. There may be more, but it is perhaps the logan stone at Treen close by the Minack Theatre which is the most famous.

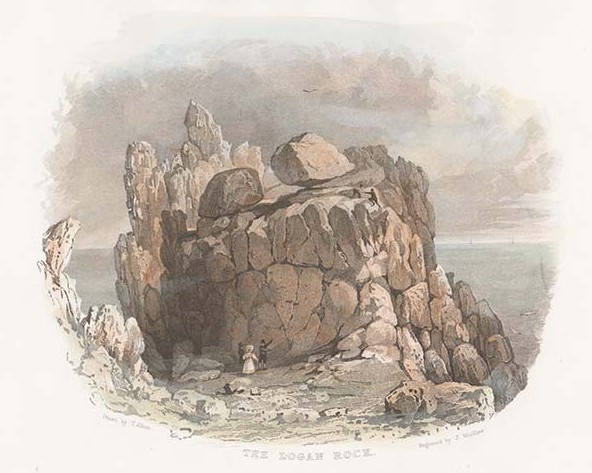

This stone was described by Dr William Borlase in 1754 in his Antiquities of Cornwall. ‘In the parish of St Levan, there is a promontory called Castle Treryn. This cape consists of three distinct groups of rocks. On the western side of the middle group near the top, lies a very large stone, so evenly, poised that any hand may move it to and fro; but the extremeties of its base are at such a distance from each other, and so well secured by their nearness to the stone which it stretches itself upon, that it is morally impossible that any lever, or indeed force, however applied in a mechanical way, can remove it from its present situation.’

Although well known locally it was through the action of man that it became far better known throughout Britain during the early 19th century. Hugh Colvill Goldsmith is not a name that many people have heard of, but by the end of 1824 he along with the Logan Stone of Treen would have become big news, and for him it would be sufficient for him to be entered into the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. There was nothing else in his whole life that would provide any distinction for his inclusion including the fact he was the nephew of the then well-known poet Oliver Goldsmith.

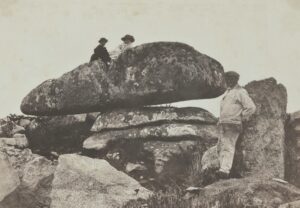

The year 1824 started for Goldsmith much as usual with him in command of the relatively small six-gun revenue cutter Nimble. They would cruise around the Cornish coast putting into harbour for supplies from time to time and apprehend smugglers or their goods when the opportunity arose. It was that fateful day 8th April 1824 that having search and dredged for smuggled goods Goldsmith and some crew landed and approached the logan stone. Having learned that it was said, as mentioned by Borlase, that this stone could not be removed from its position he and his men attempted this infamous act. Having finished their revenue work for the day Goldsmith along with nine men arrived at 4:30pm and with three handspikes attempted to lever the stone off its pivotal rock. This was unsuccessful and the nine men set to work rocking the stone with such vigour, so much so that Goldsmith became concerned it might topple onto them. An order for them to cease came too late and the logan stone toppled off its mount and fell some feet, fortunately not into the sea where it would have been lost forever.

There was huge uproar in Penzance, and it was very unfortunate for two poor families who acted as guides for visitors to the stone when they were deprived of their living. Apart from the Admiralty being informed the good and the great were also incensed by this wanton act of vandalism. Sir Richard Vyvyan of Trelowarren said that he would ‘prosecute the delinquent with the utmost vigour’.

Not only was this act mentioned in the local Royal Cornwall Gazette, which at first believed it was a hoax, but also in newspapers around Britain. Charles Dickins own magazine Household Words along with the Gentlemens Magazine were happy to report this.

It seems that Goldsmith was contrite about his act and explained his situation to his mother in a letter on 24th April. ‘For my part, I had no intention, or the most distant thought, of doing mischief, even had I thrown the Rock into the sea. I was innocently, at my God knows, employed, as far as any bad design about me, I knew not that this rock was so idolized in this neighbourhood, and you may imagine my astonishment when I found all Penzance in an uproar. I was to bid transported at least; the newspapers have traduced me, and made me worse than a murderer, and the base falsehoods in them are more than wicked. But, here I am, my dear Mother, still holding up my head, boldly conscious of having only committed an act of inadvertently. Be not uneasy my character is yet safe; and you have nothing on that score to make you uneasy. I have many friends in Penzance: amongst them the persons most interested in the Rock, and many who were most violent now see things in its true light. I intend patting the bauble in its place again and hope to get as much credit as I have anger for throwing it down.' So now came the work of restoring the stone to its original state, although many experts of the day were adamant that it could not be done.

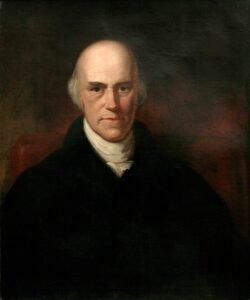

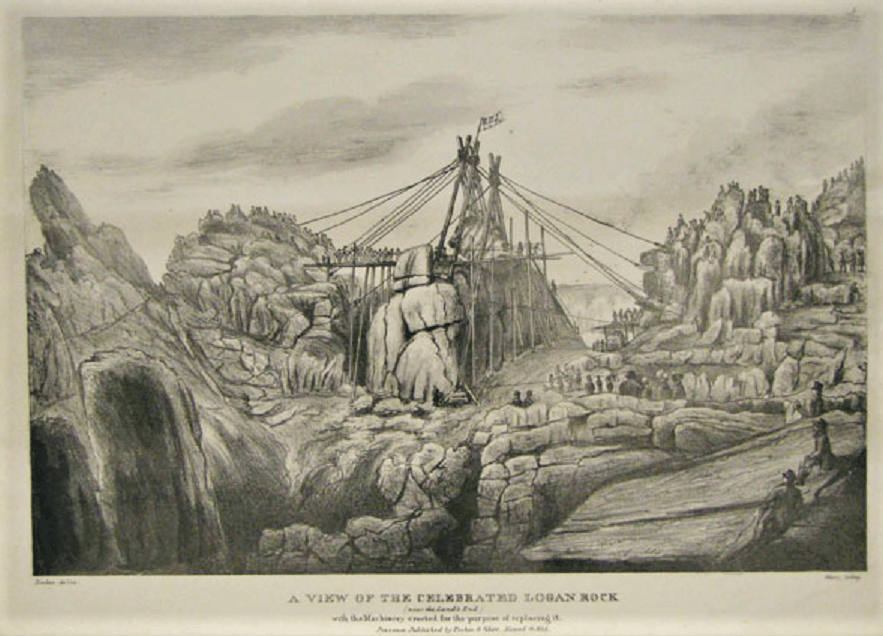

Following this incident Lieutenant Goldsmith continued his command of the Nimble in his preventive work for the Revenue Service, cruising around Cornwall looking out for smugglers and retrieving their goods. Let’s give Goldsmith some credit for his wishes to set things right, albeit that he was pressured to do it by the Admiralty with a threat to his commission. He had the fortunate support of Davies Gilbert of Tredrea in St Erth, the well-known and respected engineer, author, and politician who persuaded the Admiralty to provide the equipment at no cost as well as donating £25 himself to the cause of setting the stone back in place. The cost of labour and other expenses was to be borne by Goldsmith, which ultimately amounted to a total £130.8s 6d, a sizeable sum in those days especially for a man of little wealth.

The work began to replace the eighty-ton logan stone on 29th October and by 2nd November the rock was back in situ, albeit said by some that it didn’t quite rock as well as it had done before it was vandalised. Replacement of the rock had created an attraction in itself with thousands of people turning up to watch the spectacle. It was reported that ‘It is but justice to Lieutenant Goldsmith to say , that he evinced the greatest care and intrepidity in this difficult and dangerous undertaking, tho’ nothing can excuse his first act’. The late Cornish historian Craig Weatherhill asserted that with a series of rhythmic heaves against the south-western corner the rock will begin to move, after which the motion can be kept going with the efforts of one hand. Although Goldsmith was demonised by a great number of people, there were those who lauded him for his work in setting the logan stone back again and he benefited by being entertained by those persons.

It seems that he repaid the net debt, after Davies Gilbert’s contribution, shortly before his death along with interest. Having been promoted to the rank of lieutenant in 1809 he was never promoted further, commanding small vessels until his death at sea in 1841 on board HMS Megaera, a Hermes class wooden paddle sloop, off St Thomas island in the West Indies.

This foolhardy, but perhaps not intentionally malicious act would haunt him throughout his life, although it has given him some immortality in a national biography and remembered in print some two hundred years later.

A final postscript to this story covering another great Cornish stone monument damaged this time, albeit partially by natural causes. A great storm on 19th October 1815 had caused the capstone on Lanyon Quoit to fall, probably the final straw after various excavations under the quoit including by Dr William Borlase years earlier. Local people had raised funds to raise the monument and following the success of resitting the Treen Logan Stone Lieutenant Goldsmith and Captain Charles Giddy used the Royal Navy equipment to raise Lanyon Quoit. Little credit has been given to Goldsmith for this work, it being apportioned solely to Captain Giddy. That however is another story.

![Ertach Kernow - 19.04.2023 [1] Logan Stone of Treen](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Ertach-Kernow-19.04.2023-1-254x300.jpg)