Ertach Kernow - Lighting up Cornwall's 'Age of the Saints'

Saints are everywhere in the place names of Cornwall wherever you look. The period following the Roman legions leaving Britain has been known as the Dark Ages, although that is being contested by some historians. Certainly, the period is somewhat lacking in written history, but as more archaeology is uncovered and with scientific advances allowing more to be gleaned from what does exist it is gradually become less dark. The writings of Nennius, Gildas and the Venerable Bede, often written long after the times of events are considered by some to be of questionable value, These are now being reinterpreted as they are placed alongside other sources of information.

During the 5th to 7th centuries Cornwall was at the forefront of Christianity within the British isles, albeit of a Celtic variety. This is often known as the ‘Age of Saints’ and Cornwall has become known as the ‘Land of Saints’. These days we celebrate St Piran as our most prominent patron saint on 5th March and what is now Cornwall’s National Day. But we shouldn’t forget those other saints who were considered patron saints of Cornwall in bygone ages, and all the numerous other saints who have given their names to many towns, villages and hamlets throughout Cornwall.

Cornwall has perhaps lost a trick to our Celtic cousins in Brittany who have certainly jumped on the bandwagon of making the most of saints who have a connection with Brittany and other nations including Cornwall. Building on their existing awesome megalithic sites around Carnac, which predate the arrival of Celtic tribes and constructed during the Neolithic age, they are now assembling a collection of statures in what is known as the Valley of the Saints. A great fanfare of publicity here in Cornwall heralded the transportation, along with a Cornish delegation, and erection of St Piran. However, we in Cornwall cannot have exclusive rights to St Piran as he is also celebrated with patronages in Brittany.

Cornwall during the medieval age had very few towns and was largely made up of scattered villages, hamlets and farmsteads. As Canon Professor Nicholas Orme points out in ‘The Saints of Cornwall’ churches often stood in isolation and were named after the saint they commemorated and then applied to the parish in which the church stood. Communities would in time grow up around those churches, forming the towns and villages we know today. Often a village or town name is not obviously named after a saint, however when looking at the use of the Cornish language in naming communities it becomes clearer. Eglos in Kernewek, the Cornish language, means church so Egloskerry is the church of Keri. Several have lost their prefix ‘St’ such as Goren, Ladock, Probus and others, but often the name of parish church within those communities still retains its original name and of the community.

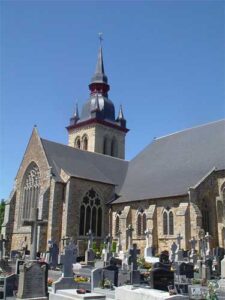

[Left] St Probus & St Gorannus Churches in communities examples of Cornish towns or villages which have lost the saint [St] prefix to their names, but remembered through the name of the church.

During mid-medieval times it was St Petroc who was the senior patron saint in Cornwall, and it was at present day Padstow he erected his first church. The name of Padstow has evolved, called Lannwedhenek in modern Cornish [SWF] this evolving from Lanwethinoc, Cornish place names beginning Lan often representing some enclosure or churchyard. From another early name Petrocstowe comes the present name of Padstow. It was in Bodmin that a major church was built and named after St Petroc and here his bones were held in a casket.

Whilst the lives, or biographical histories, of many saints were lost due to their destruction during the Reformation, those of St Petroc survive. We must be thankful to our Celtic cousins in Brittany that some of these documented lives have been preserved there, St Petroc’s in the Breton abbey of Saint Méen. It is thought Saint Méen himself originally came from Cornwall. The truth of the matter is these documented lives were often written long after the death of the person and usually includes information, mostly relating to the cult or later events, concerning the saint’s miracles. The only life of a saint with any possible value is of St Samson.

The story goes that St Petroc arrived in Cornwall in the early 6th century and after founding his abbey or monastery at Padstow travelled around the British Isles and Brittany, where his cult spread. After St Petroc’s death in supposedly 564 at Padstow, his bones were moved to Bodmin about 981. Incursions by Danes, or as we would call them Vikings were common even in Cornwall and it was probably deemed safer to keep them further inland. However, in 1177 a disgruntled monk named Martin stole St Petroc’s bones and took them to the Abbey of Saint Méen in Brittany. The theft was discovered after miracles were being attributed to the bones and the tomb of St Petroc in Bodmin was found to be empty. King Henry II sent his Vice Chancellor Walter de Coutances to affect a return of the bones, which he fortunately did, the eminent historian John Gillingham called Coutances "one of the great fixers" of his time. Coutances returned the bones in the ivory casket which can be seen in St Petroc’s Church Bodmin today. Subsequently the bones were hidden with the casket during the Reformation, lost and then rediscovered in 1831 and then stolen again before being recovered from Sheffield. By that time, the bones had vanished, presumed lost. The casket was stored in the vaults at Barclays Bank by the new owners, the Bodmin Town Council, and brought out on special occasions. However, a downpour at one event led to it being returned to the church in specially protected display case in 1957.

But what about the bones? They did not all vanish during the 20th century it would appear poor old St Petroc was having his bones nibbled away at and dispersed over a long period of time. Following the return of the bones to England in 1177 they did a tour in the casket, firstly to Winchester for King Henry II to look at. He kept three joint bones for himself and sent a rib bone in a silver case to St Méen to keep the monks there onboard. They then went via Exeter back to Bodmin where with great ceremony they were displayed. The Lord Bishop then split the bones, the skull and upper bones going into the casket and the remainder in a gilded shrine. To all those who visited the shrine he granted various indulgences from penance and purgatory. During medieval times bones of saints were items of great value, undoubtably various bones were filched over the centuries. Mont Saint-Michel in France claimed in 1396 to have bones of St Petroc and a church in Finistere obtained relics of St Petroc from the Archbishop of Rennes in 1875. A surprising discovery indicated in a Parisian held religious book stated, that in 1646 the abbey of St Méen possessed a portion of the skull of St Petroc along with those of St Meen himself, St Judicael and St Austell.

It may be the bones of St Petroc, Cornwall’s venerated medieval patron saint, returned in 1177 were not necessarily as complete as maybe expected. Perhaps some are still stored around Brittany at various religious sites and elsewhere.

![[36] Voice - Ertach Kernow-030321A - Lighting up the Age of Saints [S] Ertach Kernow - Lighting up the Age of Saints](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/36-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-030321A-Lighting-up-the-Age-of-Saints-S-232x300.jpg)

![[36] Voice - Ertach Kernow-030321B - Lighting up the Age of Saints [S] Ertach Kernow - Lighting up the Age of Saints](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/36-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-030321B-Lighting-up-the-Age-of-Saints-S-225x300.jpg)