Ertach Kernow - Cornwall’s Arthurian legacy

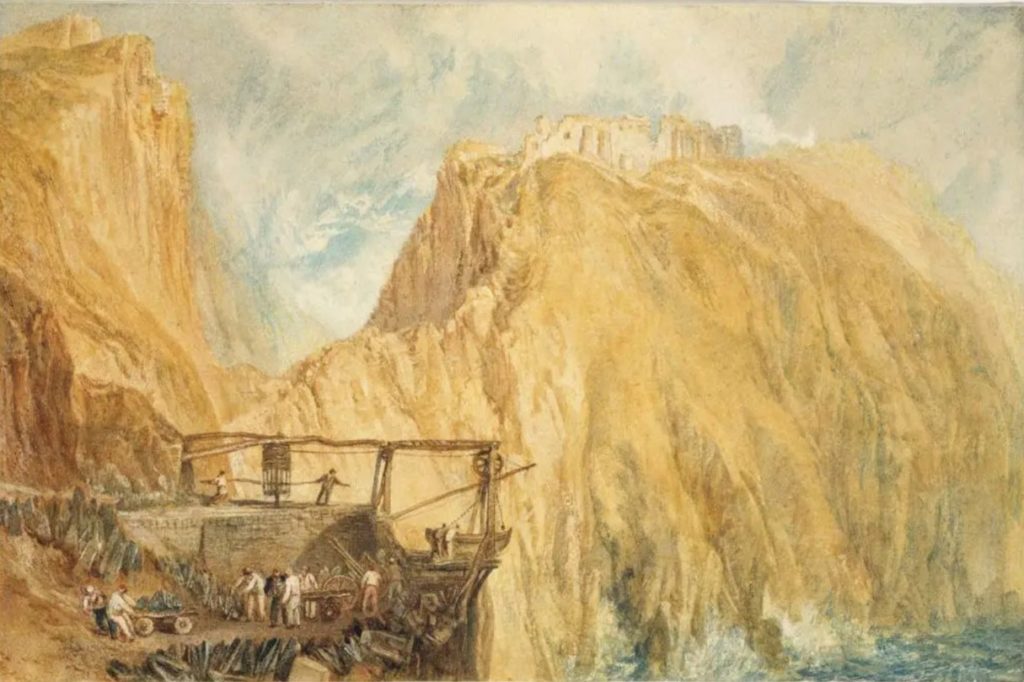

King Arthur is one of the many legends of Cornwall that persists almost as historical truth, although there is no real evidence that he or anyone like him actually had any Cornish connections whatsoever. Arthur’s name certainly draws the crowds and at Tintagel Castle English Heritage and the nearby village have now built a whole industry around the Arthurian legend. Without the author Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth including Arthur in his book Historia regum Britanniae, The History of the Kings of Britain this may never have taken place. There is no doubt that Tintagel is an ancient site and the archaeological discoveries there are of huge importance, including the vast amounts of pottery sherds and artefacts collected. This in itself would have made Tintagel a place of great interest to many interested in genuine history and archaeology, but probably insufficient go have allowed for the construction of the original crossing to the island yet alone the recent bridge now allowing thousand more visitors to cross.

Of course, the later medieval construction is the real draw and in the minds of most people this is King Arthur’s castle despite efforts to tell the real historic truth about it. Cornwall and those especially connected to Tintagel as a money spinner such as English Heritage and the village have a lot to thank, a still almost overlooked 13th century earl of Cornwall for. Richard Earl of Cornwall became owner of the area now occupied by the castle in 1233 through a property deal with the then owner Gervase de Tintagel, which included the manor of Merthen near the Helford River and two other manors. Gervase’s father Robert de Hornicote had changed the family name to de Tintagel, had he done this to benefit from the Geoffrey of Monmouth Arthurian story which had proved so popular.

So, who was Geoffrey of Monmouth who might be termed the ‘Father of Arthurian Legend’ or alternatively Arthurian tourism. Perhaps Tintagel should have a statue to him similar to that close to Tintern Abbey in Monmouthshire, because of him it has much to be thankful. Geoffrey was born in Wales or along the Welsh Marches about 1095, based on the first record of him witnessing a charter in 1129. Before 1135 the earliest existing writing known by Geoffrey are the ‘Prophecies of Merlin’. Much of his work would have been based on the works of Gildas ‘On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain’ in the 6th century and Nennius a 9th century Welsh monk in his ‘The History of the Britons’ and Welsh texts existing at that time. Interesting that there was no mention of Arthur whatsoever by Gildas or Nennius. A third later work by Geoffrey was entitled the Life of Merlin. Geoffrey was consecrated as Bishop of St Asaph at Lambeth in 1152 and had died by December 1155 when his successor took office.

For someone who came from Wales how is it that Cornwall and Tintagel features in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s tale, it’s conceivable that he travelled from South Wales to Cornwall by sea and if so why? Geoffrey had dedicated versions of his Historia regum Britanniae to Robert of Caen, 1st Earl of Gloucester. Robert was the eldest, albeit illegitimate, son of Henry I and said to be his favourite. Following Henry’s death, he supported his half sister Maud in her attempt to retain the crown promised by her father, this period became known as The Anarchy. A number of manors in Cornwall were owned by Robert and it may be that through this connection Geoffrey travelled to Cornwall on the earl’s behalf. It was recorded that at the time of Robert’s death that the church of Menelidan north-east of Tintagel had been owned by him, in the manor close by the castle area. Following the conquest in 1066 this manor had come into the possession of Matilda of Flanders wife of William I, after her death in 1083 it had reverted to the Crown. On the accession of William Rufus in 1087 his younger brother Henry requested the manor, and it was agreed. However, William Rufus went back on his word and the manor was given to Robert Fitz Hamon as part of the Honour of Gloucester. When Fitz Hamon died leaving daughters, one of whom the heiress Mabel became a ward of Henry, who after gaining control endowed it on his son Robert of Caen. Perhaps Geoffrey in travels to Cornwall may have seen the high cliffs and the remains of earlier occupation and monastery, now all proven to have existed through 20th century archaeological excavations and was captivated sufficiently to include them in his story.

At the time of writing there was no recognisable castle from which Geoffrey could have based his history or the birth of Arthur. It has been speculated that some castle building were begun by a younger son of Henry I, also illegitimate, Reginald de Dunstanville who indue course became Earl of Cornwall around 1140. Reginald was much younger than his half-brother Robert of Caen and although he may have begun construction at Tintagel this would have been later than Geoffrey’s work. Was Reginald the first earl of Cornwall to be inspired to start a castle by Historia regum Britanniae completed just a few years earlier? Certainly, the archaeologist Radford Raleigh who carried out excavations during the 1930’s considered the earlier medieval work was undertaken by Reginald and that the even earlier buildings related to a Celtic monastery. Recent archaeological work at Tintagel has discovered far more about the site and reference to any possible work by Reginald de Dunstanville seems to have been pushed into the background or omitted with all the medieval buildings being attributed to Richard Earl of Cornwall, Reginald’s great great nephew.

That Reginald de Dunstanville and later Richard Earl of Cornwall may have wanted to create a Cornish agenda linking themselves to King Arthur, they were not the only ones. Many later kings would also create connections including Edward I who was a great Arthurian enthusiast, and it was he who built the round table now hanging in Winchester Great Hall. The Tudors trying to create some authenticity to their reign saw Henry VII naming his eldest son Arthur and Henry VIII restoring the great table and including the Tudor Rose at its centre.

It has been suggested that the actual name of Tintagel or in its earliest form Tintagol was actually an invention of Geoffrey. However, with certain Cornish elements to the name perhaps it was a latinised, misheard or misspelt version of the Cornish Dintagel, din being fort and tagel meaning choke point. Perhaps some artistic licence by Geoffrey was involved as it has never been found recorded before he wrote it. Cornish author and historian Craig Weatherhill believes that it is of Norman-French origin from tente d'agel meaning the devil’s stronghold. Other places mentioned by Geoffrey included the fort of Dimilio. The paragraph mentioning Tintagol and Dimilio in the Historia regum Britanniae reads; ‘But Gorlois did not dare to meet with him, because his number of armed men was less. Wherefore he chose to fortify his towns until he had obtained help from Ireland: and being more anxious for his wife than for himself, he placed her in the town of Tintagol on the shore of the sea, which he considered a safer refuge. But he himself entered the fort of Dimilio, lest, if misfortune should happen, they should both perish at the same time.’ The hillfort that is now the site of the Church of St Denys at St Dennis is a popular location for Dimilio which was once part of the manor of Dimelihoc and an ancient Iron Age site.

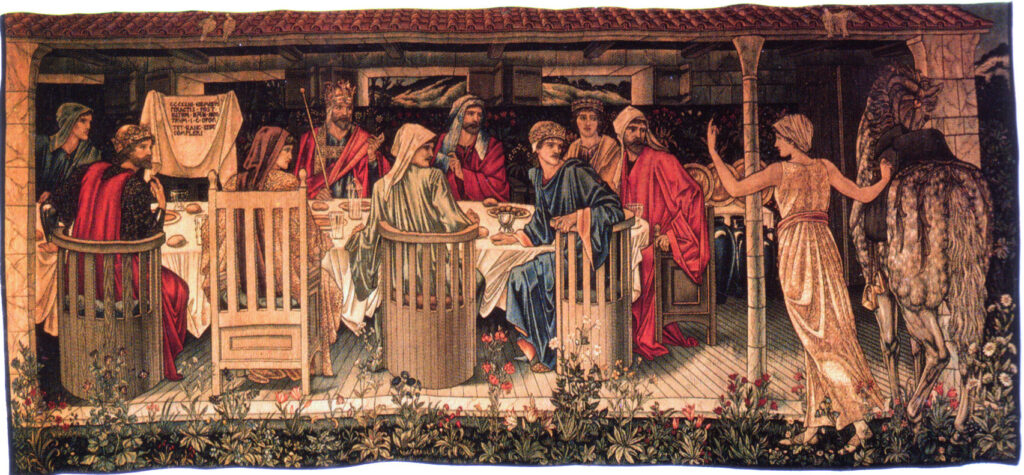

The stories we know today include the many additions to the original Arthurian legend. The medieval poet Robert Wace expanded on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work including Arthur, completing ‘Roman de Brut’ in 1155. Chrétien de Troyes the French poet added many more characters we know today to the wider legend including Lancelot, Percival, Gawain and introducing the Holy Grail. Whereas Geoffrey may have aimed for his work to be a historic record, Chrétien de Troyes is certainly a romanticised fiction, and he is often credited as being the inventor of the modern novel. Later poetic works by Sir Thomas Malory in the 15th century, Alfred Lord Tennyson the Poet Laureate in the 19th century and even the Vicar of Morwenstow the Reverend Stephen Hawker of Trelawny fame added to the spread of this growing tale and legend. Geoffrey’s Historia regum Britanniae was acknowledged as genuine history well into the 16th century, but now accepted as an important piece of medieval literature rather than a history. It provides a doorway into the minds of our ancestors, their beliefs and literary interests. The basis of many films, television series, theatre performance and art the Arthurian story is a great one and Cornwall has managed to hang onto its slice of that valuable cake.

The question of who Arthur was and did he really exist has been the subject of numerous books over the centuries with many differing thoughts and conclusions. That there was a powerful Celtic Briton war leader who fought the Saxons is accepted by most academics, who he was perhaps we will never know. Personally, one of my favourites theories is through the proto-Celtic word arto meaning bear. This was perhaps a nickname for someone big and strong and well-known and recorded from that time in history. Later Arto was transformed into Arthur and his real name and nickname have never been clearly linked.

![Ertach Kernow - 05.07.2023 [1] King Arthur, Cornwall's Arthurian legacy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Ertach-Kernow-05.07.2023-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 05.07.2023 [2] Cornwall's Arthurian Legacy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Ertach-Kernow-05.07.2023-2-254x300.jpg)

![[158] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 5th July 2023 - Rescorla Centre, Arthurian Art & Archaeology Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 5th July 2023 - Rescorla Centre, Arthurian Art & Archaeology](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/158-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-5th-July-2023-Rescorla-Centre-Arthurian-Art-Archaeology-300x293.jpg)