Ertach Kernow - Helston an early historic Cornish town

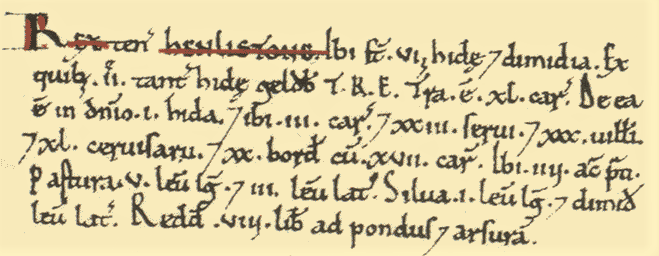

Over the past couple of years I’ve made small references to the early historic Cornish town of Helston and Cornwall’s tenth largest town by population, depending on which statistics are used. Perhaps it’s time to give it a better look especially as it is one of Cornwall’s most historic towns. At the time of Domesday Book in 1086 it was recorded as Henlistone made up of the Cornish name elements hen (old or longstanding) lis (court or administrative place) and the Saxon tun or ton (enclosed village or manor). This helps illustrate it as a well-established settlement long before Domesday when it was held by the Crown. When William I took it over from Harold Godwinson England’s last and short reigning Saxon monarch it was one of the largest and valuable manors in Cornwall worth eight pounds per annum.

Later tin streaming took place along the Cober river, and this would have added value to those owning the manor. Although records prior to the 13th century are scarce there are mentions in the Pipe Rolls showing it was a growing town. The town was rented out by the king, possibly Henry II, to Odo son of Frewin for £4 a year. He took rents from townspeople, but seemingly raising their status as well as providing 33 acres of common land during his tenure.

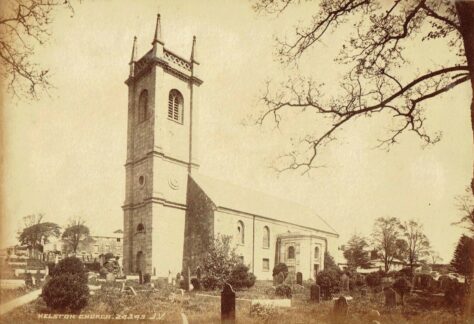

At the centre of growing medieval communities was the church. By 1208 Helston had a church called the ‘Chapel of St Michael of Hellestone’, chapel of ease to the mother church at Wendron. It was likely this church, said to have been 126 feet long with a spire 90 feet high, that was struck by lightning and caught fire in 1727. It remained in a ruinous state until was pulled down and rebuilt between 1756 and 1763, paid for by Francis 2nd Earl of Godolphin at a cost of £6,000. Since its first opening there have been a number of works completed. In 1838 various extensions then by a controversial transformation in 1970 following a two-year closure due to structural faults found in the chancel arch. Further modernisation has taken place during the 21st century making it internally very different to the 18th century church. An ornate monument in the churchyard marks the grave of Henry Trengrouse, inventor of the rocket life-saving apparatus for sailors. There were a couple of other ecclesiastical buildings within Helston, a chantry chapel of St John the Baptist situated a quarter of a mile from the parish church founded by John Boleghe. Also, a chapel originally established by the earl of Cornwall known as Chapel of our Lady, which was outside the jurisdiction of the Vicar of Wendron, later supported by the Cordwainers Guild. This became a popular place of worship becoming wealthy but was suppressed in 1547 during the Reformation afterwards converted into the Coinage Hall and demolished during the early 19th century. A memorial and mission church known as All Saints Church was completed as a chapel of ease in 1888, on becoming redundant as a place or worship it was converted into a residence in 2013.

As early as 1411 a hospital is mentioned named after St Mary Magdalen in Bishop of Exeter Stafford’s register, and in 1435 in Bishop Edmund Lacy’s register. Known later as The Hospital of St John the Baptist its foundation was attributed to an early archdeacon of Cornwall, although John Leland mentions a member of the Killigrew family.

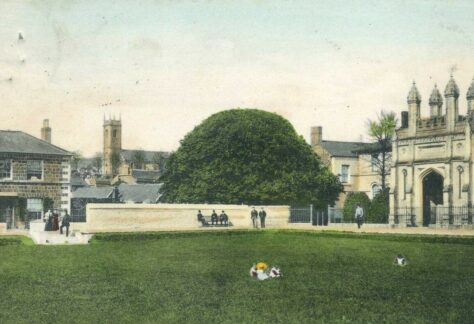

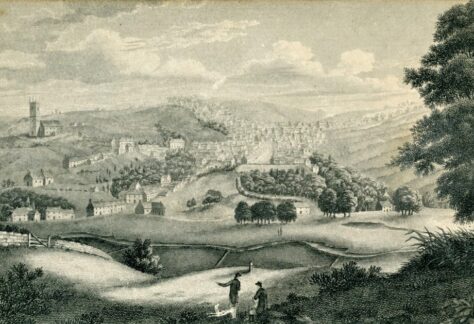

As with other Cornish towns during the medieval period it was only through obtaining Charters of Privileges that a town could really benefit. It was through the notorious King John that Helston benefited, his financial plight probably allowed them to buy one from him when requested in 1201 and was later confirmed by later monarchs. The amount paid was 40 silver marks plus a palfrey, a horse possessed of a smooth, ambling gait, plus doubling the annual rent to £8 per annum. In 1259 Richard Earl of Cornwall visited and gave a further charter with additional privileges of the town mills, the water of the Cober and lands around the town. Needless to say, there was a cost, the rent was increased to £12 per annum. A little later on a castle, probably a fortified or crenelated manor house, was established on the site that is now the bowling green. Built by Edmund Earl of Cornwall between 1272 to 1300 by the time of William of Worcester, the English antiquary and chronicler, who noted in 1478 that Earl Edmunds castle at Helston was in ruins. John Leland some six decades later wrote there were the remaining vestiges of a castle. By the end of the 13th century Helston was becoming a wealthy town with few rivals closer than Truro or Penryn, the towns of Penzance and St Ives were still to become settlements of any size. In 1336 four annual fairs for three days each were granted to the burgesses of Helston.

There was stone quarrying taking place in the area, but it was through tin mining that Helston became one of the most important coinage towns in Cornwall, along with mainly Liskeard, Lostwithiel and Truro. Other towns included Bodmin, and Penzance were also used during certain periods. The discovery of china clay around 1755 by William Cookworthy at Tregonning near Helston heralded the beginning of a new major Cornish industry.

There remains the controversial question of whether Helston was ever a port town with its own harbour, opinions remain mixed. Certainly, the Cornish historian Charles Henderson believed so along with writer and traveller Daniel Defoe in the 18th century who wrote ‘Quitting Falmouth Haven from Penryn West, we came to Helston, about seven miles, and stands upon the little River Cober, which, however, admits the sea so into its bosom as to make a tolerable good harbour for ships a little below the town. It is the fifth town allowed for the coining tin, and several of the ships called tin-ships are laden here.’

The reason why not is through an interesting geographical features between Helston and the sea, Loe Pool created by Loe Bar. Many historic Cornish coastal towns had river access to the sea, but over time became silted up through mine waste sediment thereby restricting access and ultimately trade along with their original reason for existence. Although there had been issues regarding sediment settling through mine water being pumped into the Cober the creation of Loe Bar is somewhat different. There seems to be no evidence that Helston ever had a harbour and visiting Helston in 1542 John Leland comments; ‘Lo Poole is a 2. Miles in lenght, and betwixt it and the Mayn Se is but a Barre of Sand. And ons in 3. or 4. Yeres, what by the wait of the fresch Water and Rage of the Se, it brekith out, and then the fresch and salt Water metyng makith a wonderful Noise. But sone after the Mouth is barrid again with Sande. At other Tymes the superfluite of the Water of Lo Poole drenith out thorough the Sandy Barre into the Se. If this Barre might be alway kept open it wold be a goodly Haven up to Hailestoun. The Commune Fisch of this Pole' is Trout and Ele.’

The river Cober running to the west of Helston flows into Loe Pool, when much of the water entering the Pool filters out through the bar between it and the sea. However, from time to time the level of the water can cause flooding. When this happens the Bar often needed to be cut to allow the floodwater to escape. This was something that Leland also knew about and commented on, although some 50 years later John Norden made no note of it in his writings. Norden was however in praise of the fish ‘In this poole are great store of a kynde of trowte farr excedinge the freshe water trowte in bignes and goodnes; and some other kyndes of fishe.’

During the 19th century miners working the lead and silver mine at Wheal Pool discovered an ancient adit which once extended and cleared allowed the surplus water to drain into the sea. Occasionally the Bar still needed to be cut should the adit have become clogged and the water not escaping fast enough.

Images of huge waves caused by south westerly storms breaking over Porthleven are well known and give an indication of the ferocity of potential weather conditions and the effect on nearby Loe Bar. Storms can have a huge effect and result in large amounts of sand being moved either on or off the Bar. Studies have shown that; ‘the formation of the Loe Bar could not have taken place as recently as the 13th Century, as many port theory supporters agree. The high chalk flint content of the bar is proof enough of this, and a much earlier formation date (3000-4000BC) is far more comprehendible’. However, excluding the silting issues caused through later mining and allowing for continuous maintenance of a break in the Bar where viable, it is conceivable that a port or harbour could have existed helping lead to the early establishment of Helston. Perhaps this question will never be fully confirmed until some early archaeological evidence is uncovered.

![Helston - Loe Bar 6'' Map 1880 [2] Helston - Loe Bar 6'' Map 1880](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Helston-Loe-Bar-6-Map-1880-2-474x324.png)

![Helston - Loe Bar 6'' Map 1880 [1] Helston - Loe Bar 6'' Map 1880](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Helston-Loe-Bar-6-Map-1880-1-300x163.png)

![[106] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 060722A Helston historic town [S] Ertach Kernow - Helston historic town](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/106-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-060722A-Helston-historic-town-S-241x300.jpg)

![[106] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 060722B Helston historic town [S] Ertach Kernow - Helston historic town](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/106-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-060722B-Helston-historic-town-S-241x300.jpg)

![[106] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 6th July 2022 - Bridges and Museums Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 6th July 2022 - Bridges and Museums](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/106-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-6th-July-2022-Bridges-and-Museums-271x300.png)