Ertach Kernow - Daniel Defoe, travels Fowey to Falmouth

Time passes so quickly, and I have left another of our Ertach Kernow travellers stranded this time in Fowey for eighteen months. Best known for his immensely popular work Robinson Crusoe published in 1719 and Moll Flanders in 1722 our historic visitor to Cornwall, Daniel Defoe, would in time produce ‘A Tour Thro' the whole Island of Great Britain’ published between 1724 and 1727. Just over two decades after Celia Fiennes tour around Cornwall the Cornish landscape was in the early stages of major change with steam engines beginning to appear, allowing mines to go increasingly deeper. Wheal Vor it is said was the first mine to use gunpowder to blast ore from the lode in 1689 and understood to be the first mine in Cornwall to install a Newcomen steam engine by 1710.

Defoe actually made the trips around Britain himself not relying on others as some authors had. He wrote as part of his preface to volume one ‘The observations here made, as they principally regard the present state of things, so, as near as can be, they are adapted to the present taste of the times: The situation of things is given not as they have been, but as they are; the improvements in the soil, the product of the earth, the labour of the poor, the improvement in manufactures, in merchandizes, in navigation, all respects the present time, not the time past.’ We are therefore looking at what he observed of Cornwall and his thoughts during his travels.

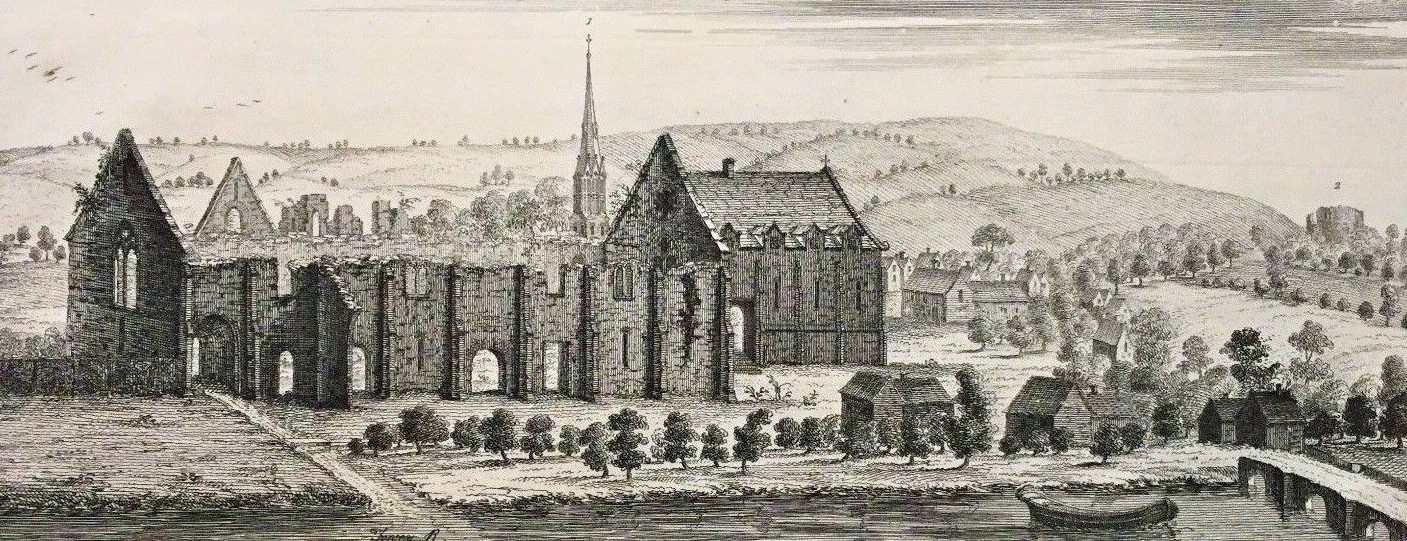

Continuing on Cornwall’s south coast, from Fowey he takes a trip up the Fowey River to Lostwithiel. Defoe acknowledges that at one time Lostwithiel was an ancient and once flourishing town but brought to its knees by the silting up of the river on which its early trade depended. He does comment on Lostwithiel’s positive aspects saying; ‘This town of Lestwithiel, retains however several advantages, which support its figure, as first, that it is one of the Coinage Towns, as I call them, or Stannary Towns, as others call them. The common gaol for the whole Stannary is here, as are also the county courts for the whole county of Cornwall.’

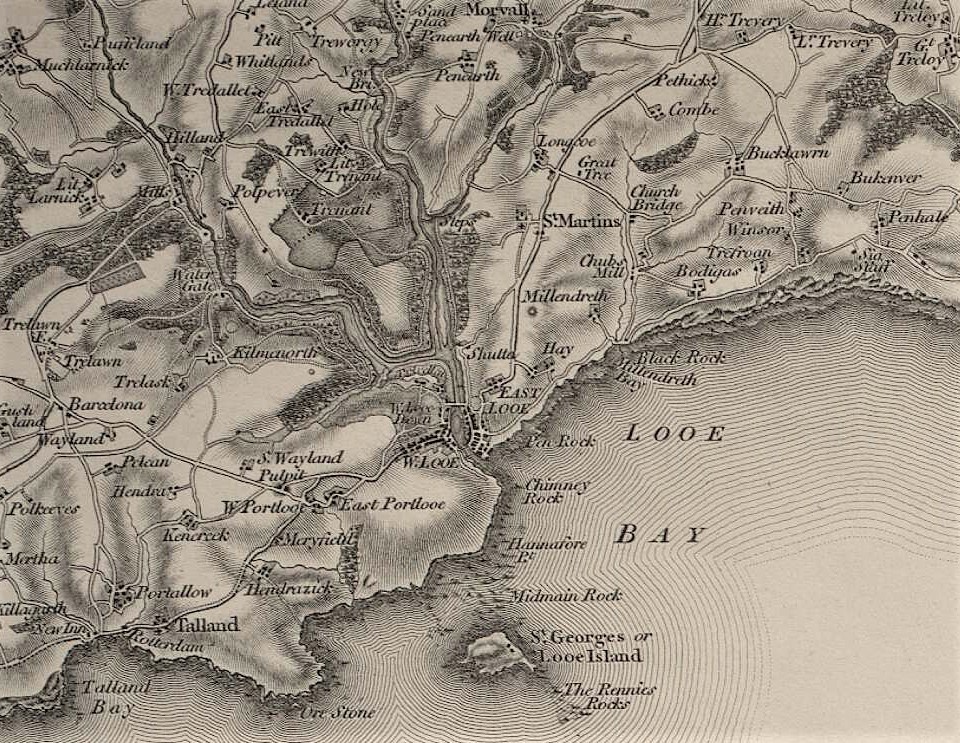

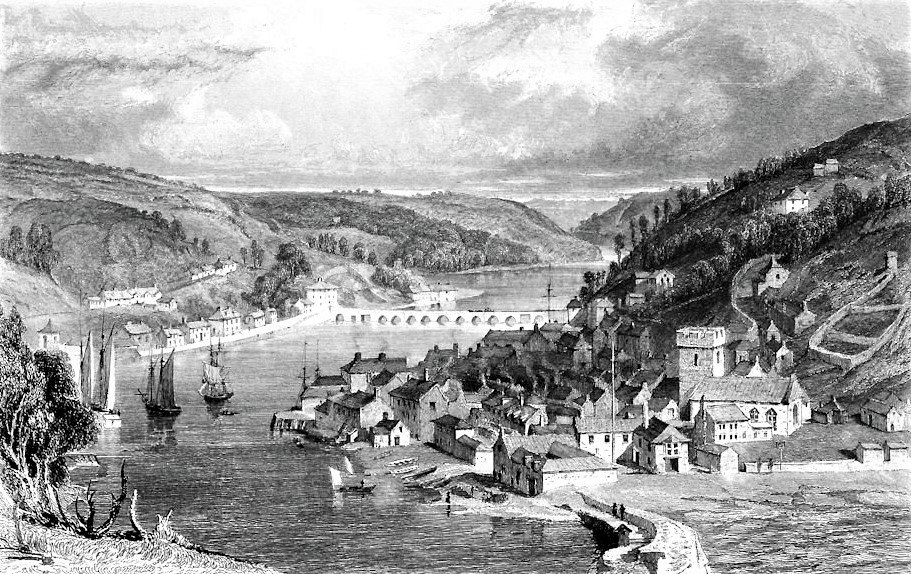

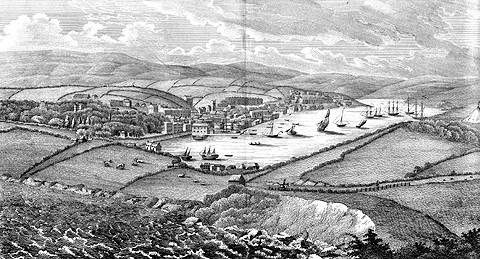

Moving along the coast Defoe arrives at Looe of which he is very complementary, describing them as two small towns facing each other over the River Looe telling readers they are good trading and fishing towns. He describes the bridge as a ‘very beautiful and stately stone bridge having fifteen arches’. Something described as beautiful and stately should have a little more said about it. The bridge at Looe replaced an earlier timber structure built around 1400 and following its burning in 1405 replaced with the stone bridge where construction began in 1411. It took 25 years to complete with a length generally given as 384 feet and according to Defoe had 15 arches. Other writers gave different numbers of arches and one of the earliest travellers William of Worcester in 1478 referred to the bridge as Low Brygge and described it as maximus pons meaning the largest bridge in Cornwall. Sadly, left to decay and later replaced upstream in 1855 Charles Henderson suggested had it been wider, as at Wadebridge, it would have been spared and ‘it was "a thousand pities the builders had not done so.’

As for the towns of Looe Defoe wrote ‘East Loo, was the antienter corporation of the two, and for some ages ago the greater and more considerable town; but now they tell us West Loo is the richest and has the most ships belonging to it: Were they put together, they would make a very handsome seaport town. They have a great fishing trade here, as well for supply of the country, as for merchandize, and the towns are not dispisable; but as to sending four members to the British Parliament, which is as many as the city of London chooses, that I confess seems a little scandalous, but to who, is none of my business to enquire.’ Of course, the Great Reform Act of 1832 would put paid to that and other Cornish historic parliamentary inequities.

Passing Tywardreath, which he describes a town of no great note Defoe mentions Tywardreath Bay, now known as St Austell Bay, but not St Austell at all. St Austell was then just a small market churchtown around its 13th century church and had not yet benefitted from the growth of the Polgooth tin mine that would become known as the greatest tin mine in the world and later Cornish white gold, china clay.

Travelling westwards towards Falmouth, Daniel Defoe notes the two Henriquian castles. ‘St. Mawes and Pendennis are two fortifications placed at the points, or enterance of this haven, opposite to one another, tho' not with a communication, or view; they are very strong; the first principally by sea, having a good plat form of guns, pointing thwart the channel, and planted on a level with the water; but Pendennis Castle is strong by land as well as by water, is regularly fortified, has good out works, and generally a strong garrison; St. Mawes, otherwise call'd St. Mary's has a town annex'd to the castle, and is a borough, sending members to the Parliament. Pendennis is a meer fortress, tho' there are some habitations in it too, and some at a small distance near the sea side, but not of any great consideration.’

Entering Carrick Roads, which Defoe refers to in its entirety as Falmouth Havens he waxes lyrical saying ‘It is certainly next to Milford Haven in South Wales, the fairest and best road for shipping that is in the whole isle of Britain, when there be considered the depth of water for above twenty miles within land; the safety of riding, shelter'd from all kind of winds or storms, the good anchorage, and the many creeks, all navigable, where ships may run in and be safe, so that the like is no where to be found.’ Carrick Roads in fact is understood to be the third largest natural harbour in the world and around its shores are found some of the oldest coastal communities in Cornwall. Looking at the town of Falmouth Defoe has much to say and is most impressed. ‘The town of Falmouth is by much the richest, and best trading town in this county, tho' not so antient as its neighbour town of Truro.’ However, it should be noted at that time mining on a really industrialised scale had just begun, some parts of Cornwall would through their mines later be referred to as the richest places in the world. Although Truro was during the early 18th century less of a trading town than Falmouth, due to silting up of the higher reaches of the River Fal, it was still important. Although larger ships of over 150 tons could no longer dock there smaller vessels still could and Truro merchants had invested in wharves and storage facilities at Falmouth. These Truro merchants would also receive duties for use of these facilities, which Defoe acknowledges.

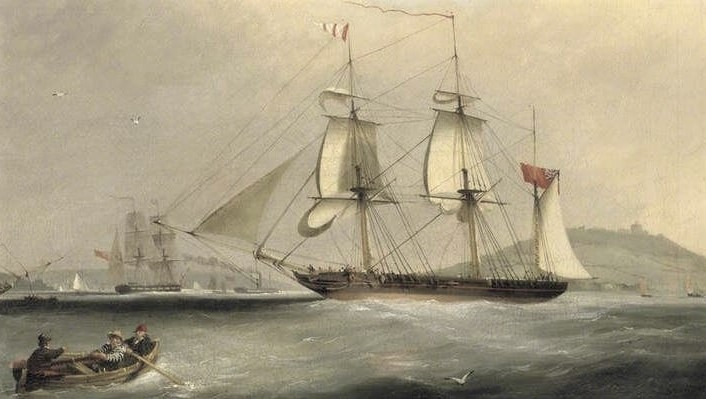

Defoe recognised that the Falmouth Packets had a major impact on the growth and wealth of Falmouth, since inception of the town as a Royal Mail packet station in 1688. The speedy lightly armed vessels carried mail and messages around the growing British Empire for nearly 200 years until 1850. Captains were also able to carry private goods and passengers on their voyages. He also makes an interesting comment regarding additional profits which helped boost Falmouth’s mercantile wealth saying; ‘between this port and Lisbon, there is a new commerce between Portugal and this town, carried on to a very great value.’ Defoe continued to spill the beans ‘ It is true, part of this trade was founded in a clandestine commerce, carried on by the said packets at Lisbon, where being the king's ships, and claiming the privilege of not being searched, or visited by the custom-house officers, they found means to carry off great quantities of British manufactures, which they sold on board to the Portuguese merchants, and they convey'd them on shoar, as 'tis supposed without paying custom.’ So, it seems enterprising Cornish seafarers and merchants not only made money through smuggled goods into Cornwall, but also by aiding and abetting illegal export as well.

There was also traditional Cornish occupations of which Defoe writes; ‘Here is also a very great fishing for pilchards, and the merchants for Falmouth have the chief stroke in that gainful trade.’ Not only would the merchants of Falmouth have profited from the pilchard fishing at Falmouth, but also as the major point of export from fishing carried out by the towns and villages surrounding Carrick Roads. This included Truro, which also had for a time a pilchard fishery although located quite far from the seacoast.

If Daniel Defoe were alive today I’m sure he would be happy to live in Falmouth with its large student population encouraging a cultural atmosphere. The establishment of The Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society in 1832 some hundred years after his visit, the recent university expansion and the newly established annual Falmouth Book Festival show Falmouth’s ongoing interest in learning and cultural activities.

![Map of Falmouth Haven and the River Fal as far as Truro 1550-1600 [2] Map of Falmouth Haven and the River Fal as far as Truro 1550-1600](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Map-of-Falmouth-Haven-and-the-River-Fal-as-far-as-Truro-1550-1600-2-1024x592.jpg)

![[116] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 140922A Travels with Defoe [S] Ertach Kernow - Travels with Defoe Fowey to Falmouth](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/116-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-140922A-Travels-with-Defoe-S-238x300.jpg)

![[116] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 140922B Travels with Defoe [S] Ertach Kernow - Travels with Defoe Fowey to Falmouth](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/116-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-140922B-Travels-with-Defoe-S-237x300.jpg)

![[116] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 14th September 2022 - Sharing the cultural news Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 14th September 2022 - Sharing the cultural news](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/116-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-14th-September-2022-Sharing-the-cultural-news-286x300.jpg)