Ertach Kernow - Cornwall's houses and homes through history

Looking at Cornwall's houses and homes through history there is a great variety, many are still here as well as those recorded but lost through time. Large estates including country houses and gardens, smaller local heritage cottages and even ancient sites going back to the Iron Age through to the early medieval period.

Excavations illustrate the types of houses lived in since the tenth century, constructed from earth, timber and dry-stone walling in which families would have lived cheek by jowl with their animals under one roof. Yeoman farmers would have had larger living accommodation that included a cross walk or passageway and a central hearth with a vent in the roof. gradually greater interest in personal privacy saw houses grow and additional rooms included or added to existing structures.

Besides ruins and excavated sites nothing earlier than the 15th century now stands excepting the few fragments remaining following rebuilding. Houses constructed between about 1400 and 1700 can be considered in five main groupings. Hall and cross passage, tower and house/hall, central block with corner towers, fortified buildings and new manor. There remain instances of each of these in Cornwall, albeit modifications to the original building over the centuries made.

Cornwall’s isolation ensured it took time to embrace many of the trends that came from elsewhere in Britain relating to style of houses and materials used. Cornwall as a land of stone is well endowed with its own resources with which to construct buildings. Granite is strong and durable, less so the softer sedimentary killas but far easier to work, and slate which has been quarried for roofing for over 600 years. For poorer workers there was also the option to construct cob cottages, a mixture of straw earth and water often with a measure of cows urine or animal blood added. These would have been roofed with thatch well into the 19th century and beyond. The right type of timber for construction was at a premium in Cornwall, used mainly for commercial purposes in mining and shipbuilding, hence the use of stone as a substitute.

Richard Carew in his Survey of Cornwall of 1602 noted ‘Quarries are of sundry sorts and serve to divers purposes. For walling there are rough and slat; the rough maketh speedier building, the slate surer. For windows, dornes and chimneys, moor stone carrieth the chiefest reckoning. John Norden who had toured Cornwall in the late 16th century was also enamoured with moor stone and wrote ‘a stone called moar stone.. very profitable for many purposes, in building most firm and lasting; weather nor time can hardly penetrate them… They make of them, instead of timber, manye postes for their howses, doreposts, chimny and wyndow peeces.’

Cornish medieval homes were characterised as being solid weather resistant buildings with low lines. Richard Carew noted in his survey. ‘The ancient manner of Cornish building was to plant their houses low, to lay the stones with mortar of lime and sand, to make the walls thick, their windows arched and little, and their lights inwards to the court, to set hearths in the midst of the room for chimneys, which vented the smoke at a lover in the top, to cover their planchings with earth, to frame the rooms not to exceed two stories, and the roofs to rise in length above proportion, and to be packed thick with timber, seeking therethrough only strength and warmness.’

The end of the Tudor era c1570 through to the Stuart period of 1640, prior to the Civil War, saw a period of political stability leading to what has become known as the Great Rebuild. Castles and fortified manors were being abandoned by the rich and powerful and a period of construction of large and often ostentatious country houses took place. There were housing improvements for those of middling wealth including country squires, yeomen and husbandmen as well as within towns where improved trade created wealth allowing rebuilding of earlier homes. It was now Cornwall’s housing designs began reflecting England’s building fashions for larger country houses.

Of the properties being constructed during the Great Rebuild, when Carew’s Survey of Cornwall was first published it says ‘now a days, they seat their dwellings high, build their walls thin, lay them with earthen mortar, raise them to three or four stories, mould their lights large, and outward, and their roofs square and slight, coveting chiefly prospect and plea sure. As for glass, and plaster for private men's houses, they are of late years introduction.’ None of this made a great deal of difference for ordinary folk he noted, ‘The poor cottager contenteth himself with cob for his walls’.

Bricks were starting to be used in a greater number of buildings from the 16th century, Hampton Court being a notable English one. However, they were not successful in Cornwall as Richard Carew mentions, ‘As for brick and lath walls , they can hardly brook the Cornish weather; and the use thereof being put in trial by some, was found so unprofitable, as it is not continued by any.’ A footnote added ‘It is observed, that the sharpness and saltness of our air pierceth through the bricks , so that the walls are continually moist.’

Rooms that had specific purposes were being created and open hearths were being replaced by fireplaces with chimney’s. Simple chimney’s developed to become multiflued with fireplaces in a number of rooms and in the homes of the wealthy very elaborate chimneys were a feature for the upper classes to show their affluence. Even with the changes in building fashions during the period of the Great Rebuild many medieval houses continued in use well into the 17th century. Then as now the size or quality of people’s houses did not necessarily reflect overall wealth. History has shown many ruining themselves to increase social standing, whilst others lived quietly in unassuming properties their wealth accumulated in goods and chattels.

Considering some remaining and lost buildings there are ancient Iron age sites at Chysauster and Carn Euny as well as the early medieval site at Mawgan Porth. A later 13th century site is the moated manor house at Penhallam Manor in North Cornwall. Originally held by Richard Fitz Turold around the time of Domesday it started as a moated fort, later developing into the building which we can now see the foundations of following the excavations of 1968 and 1973. This structure was commenced from 1180 onwards later falling into ruin through disuse by the mid-14th century. It is a protected scheduled monument managed by English Heritage and open to visitors.

Mawgan Porth medieval village has been maintained by Newquay Old Cornwall Archaeological Group since 2014

An existing 15th century building of the hall and cross passage type is the old Truthall Manor House near Helston. This had a hall with a cross passage separating it from private chambers with possibly a gallery over part of the hall. A similar design was to be found at the medieval farmhouse at Methrose, Luxulyan. This property was split post World War II into two residences.

Pengersick Castle is an example of a 16th century tower and hall/house construction. The hall now gone can be seen as ruins in 18th century engravings, rooflines a result of previous buildings can still be seen. Built in 1510 it was later extended, with family living space in the tower. Lysons Cornwall edition of Magna Britannia 1814 says ‘There are considerable remains of an ancient castellated mansion on this estate, called Pendersick Castle, the principal rooms in which are made use of as granaries and hay-lofts; one of them, which is nearly entire, is wainscotted in panels; the upper part of the wainscot is ornamented with paintings, each of which is accompanied with appropriate verses and proverbs in text hand’.

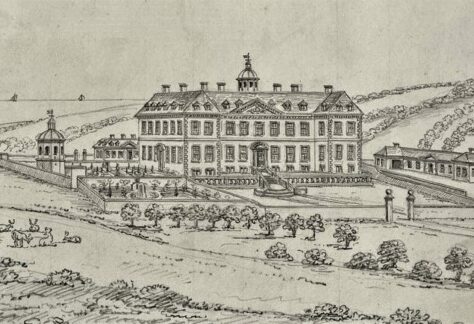

Mount Edgcumbe House was built as a house with corner towers by Sir Richard Edgcumbe in 1547. It was later enlarged through the 17th to 19th centuries by successive generations. Burnt out by incendiary bombs in 1941 it was restored post World War II and now owned jointly by Cornwall Council and Plymouth City Council. It is open to the public along with the gardens which are free to visit. Richard Carew, who was grandson to Sir Richard, tells us ‘The house is builded square, with a round turret at each end, garretted on the top, and a hall rising in the midst above the rest, which yealdeth a stately sound as you enter the same’. The round towers were replaced by octagons in the 18th century reconstruction with the hall being increased in height along with other major work during the 17th century rebuild.

Defensive buildings in Cornwall relate to the castles built around the coast by Henry VIII include those at Pendennis and St Mawes. Great Rebuild buildings of the late 17th and early 18th centuries include the lost house of Stowe built for the Grenville family, near Kilkhampton in 1680. This was regarded by Dr Borlase as the noblest house in Cornwall and the west of England. Built close to the site of the former manor house it stood high and exposed for all to see, constructed of brick with large windows. At the time it was considered incomparable in Cornwall. Following the death of the builder John Grenville Earl of Bath in 1701 the house became neglected and was demolished in 1739. Various fixtures still exist in other fine buildings in Cornwall and beyond. Perhaps a dream too far and bricks in such an exposed position perhaps still not a match for the Cornish weather.

![Pengersick Castle Engraving [1786] Pengersick Castle Engraving [1786]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Pengersick-Castle-Engraving-1786-300x200.jpg)

![[104] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 220622A Home sweet home trough history [S] Ertach Kernow - Home sweet home through history](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/104-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-220622A-Home-sweet-home-trough-history-S-243x300.jpg)

![[104] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 220622B Home sweet home through history [S] Ertach Kernow - Home sweet home through history](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/104-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-220622B-Home-sweet-home-trough-history-S-240x300.jpg)

![[104] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 22nd June 2022 - Tansys Golowan Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 22nd June 2022 - Tansys Golowan](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/104-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-22nd-June-2022-Tansys-Golowan-270x300.png)