Ertach Kernow - Cornwall's Environment and Culture

Cornwall’s environment is an important factor relating to its wider historic and cultural heritage and vice versa. What most people understand by environment is what they can see as they travel around Cornwall. Historic England write in the introduction to their latest Heritage and the Environment publication; ‘Our cultural heritage shapes places, landscapes and seascapes, leaving physical evidence in the form of field systems, paths, routeways, buildings, coastlines, water and the biodiversity and land use activities they support. Our cultural heritage is a fundamental component of our environment – which is far from static. It also reflects the natural qualities of these places. Their geography, climate and geology have all influenced settlement patterns, industrial processes, building design and materials and subsistence activities.’ From this can be seen that the integrated character of Cornwall’s and its heritage is made up from multiple factors.

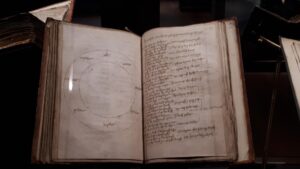

Cornwall’s Celtic language once on the edge of extinction is now undergoing a substantial revival. The Celtic Brythonic language was once spoken throughout the whole of Britain albeit differing but generally understandable. The Pictish form spoken in Pictland now Scotland gradually died out and was totally subsumed by the Gaelic form of Celtic through the 9th to 11th centuries. The Dál Riata kingdom had expanded from Northern Ireland into Pictland and believed by many scholars to have merged with it in the 9th century. Cumbric another Brythonic language spoken in the north of England and southern Scottish lowland was replaced by early English by the 12th century. Nothing substantial remains of these languages excepting through place names. Welsh survived but pushed into the far west and north around Eryri (Snowdonia) and Cornish was pushed to the far west of Cornwall before almost becoming extinct. Perhaps it could be said that geography and isolation saved the Welsh and Cornish languages being lost early in the medieval period. Cornwall’s unique language is the most important element in recognition by the Council of Europe and later the UK government for the Cornish national minority. Protection of the Cornish national identity through the Framework convention for the protection of national minorities and its language through the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages is crucial to Cornwall’s future as a Celtic nation.

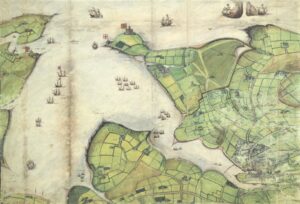

Many of Cornwall’s buildings exist as a result of geography. Early defensive positions from Bronze Age hillforts occupied high ground overlooking valley’s with tracks and in time major transport links. Consider the position of Castle an Dinas outside St Columb Major with its close proximity to the A30, an early trackway, with many recent archaeological finds along it. Later in the medieval period castles would be constructed, originally timber but later stone at Launceston, Trematon and Restormel, which still exist. There are also some little more than minor ruins and others that have vanished completely such as Cardinham, Tregony, Kilkhampton, East Leigh Berrys, Ruan Lanihorne, Truro and many more. These were along with later small defensive redoubts such as those at Fowey and Polruan built to control and area or defend and protect river crossings and harbours. The last castles built in Cornwall were the Henrician castles of St Mawes and Pendennis constructed to protect Carrick Roads from the Spanish during the 16th century. These later castles protected deep, and weather protected natural south coast harbours created by climate change many thousands of years ago. Once again geography played its part causing human environmental action leaving us with historic legacies to enjoy today. However, one castle in particular was not necessarily constructed with geographical defensive reasons in mind. Tintagel constructed on an ancient site, built by Richard Earl of Cornwall around 1240 is an anomaly. There is nothing to protect at Tintagel and the castle was not in a militarily strategic position in Cornwall. The suggestion is that Richard built the castle to ingratiate and connect himself to Cornwall through the legend of King Arthur written by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain) some hundred years previously. Basically, what might be termed in later centuries a folly, but built a result of literary culture and myth.

More Cornish town and parish councils are beginning to appreciate the importance of their historic town buildings which give the community something to be proud of. Attractively designed and built with good quality stone these often shine like jewels amongst the tragic modern utilitarian unattractive structures of more recent times. The wealth that was created during Cornwall’s golden mining age allowed for greater extravagant construction with carvings and other adornments on even ordinary shop frontages, albeit you often need to look up for full appreciation.

Much has been written and talked about recently relating to Cornwall’s Cornish Stone Hedges. With over 30,000 miles of historic and ancient hedges, Cornwall’s landscape is criss-crossed with these, the oldest found in the far west. Looking at some of the recent construction along the A30 and branch roads, those that haven’t already fallen down, the ill-informed would think Cornish Stone Hedges were the same construction throughout Cornwall. Most historic hedges are as wide at the bottom as they are tall with a tamped soil interior, but the stone used and the use of that stone in their construction differs throughout Cornwall depending on the rocks available. This time it isn’t geography but geology that dictates the local stone used over thousands of years and in turn the exterior design and build. Areas having mostly slate will see greater use of herringbone construction, whilst in areas with say granite the exterior will be built with blocks. Each design used to create strength and long life. These hedges help support diverse ecosystems that take decades to build and these in turn support larger wildlife and birds. Even the grazing of farm animals in and around hedges and on cliff tops can have an effect on Cornwall’s environmental heritage and biodiversity. Cornwall’s national bird, the chough which for a time had left our shores is thriving through realisation the chough needed a certain type of cliff top grass area in which to feed. Making this available has encouraged their numbers to grow following reintroduction. Preservation of historic Cornish hedges is important in ensuring landscape and biodiversity is maintained.

One of the features probably not enjoyed by some visitors to Cornwall are its many winding lanes with steep sided hedges. In the past and sometimes even now these would have been an important part of linking Cornwall’s obscure rural farming communities. There are also the ancient bridges that cross over the smaller rivers which have never been replaced, but sometimes bypassed. These are a legacy of times when carts and packhorses were the only way to travel around the remote place of Cornwall and should be treasured as part of our transportation heritage. It is around bridges and later on sites of industrial mining that many communities began and expanded. The reason for their beginning may be long gone but can often remembered in a place name. Sadly, from time-to-time historic bridges are damaged by oversized vehicles, more suited to motorways and city life, driven by unappreciative motorist.

As we travel throughout Cornwall looking out over the Cornish landscape we see the hundreds of engine houses and stacks that form part of our industrial mining past. These too are part of our heritage and came into being through the evolving methods of tin and copper mining over thousands of years since the Bronze Age. These have helped create part of Cornwall’s national identity and Cornish diversity from England. In turn the mining industry led to myths and folklore relating to, knockers. Other little folk of Cornish folklore included spriggans, bucca and of course piskies all with their own mythical niche. Perhaps Cornwall’s greatest export, apart from Cornish folk with their mining skills, is the Cornish pasty originating with miners and an integral part of Cornish heritage along with other foods such as hevva cake and clotted cream.

Cornwall’s distinctive landscape is in real danger of being lost as developers demolish older buildings and hedges to building nondescript housing for those able to afford them. Affordability issues amongst Cornish families leading to an exodus from Cornwall is potentially leading to the ultimate dilution of the Cornish minority and their historic culture. It is only through the hard work of organisation within the wider heritage sector educating and sharing knowledge that Cornwall’s culture is holding its own. The work recently being done in schools by providing a good base for the future is encouraging young people to engage with Cornish history and cultural activities.

Cornwall with its wonderful range of historical, cultural and environmental heritage, some unique, especially with its language makes it a place tourists who desire something different want to visit. Lose this heritage and with the cost of overseas travel now coming down and a greater range of destinations opening up Cornwall’s tourism industry could suffer. Keeping Cornwall unique through protection and maintenance of its heritage can only benefit the wider Cornish economy.

![Ertach Kernow - 22.03.2023 [1] Cornwall's Environment and Culture](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Ertach-Kernow-22.03.2023-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 22.03.2023 [2] Cornwall's Environment and Culture](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Ertach-Kernow-22.03.2023-2-254x300.jpg)

![[143] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 22nd March 2023 - Various Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 22nd March 2023](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/143-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-22nd-March-2023-Various-300x287.jpg)