In touch with Cornwall's Celtic Festivals

Cornwall's Celtic festivals have seen a revival. During recent times we have seen many historic and ancient traditions, lost as late as the 19th century, once again taking place. Both ‘Tansys Golowan’ the mid-summer bonfire celebrations and the harvest ‘Crying the Neck’ tradition have been revived by Kernow Goth, the Old Cornwall movement. Other Celtic festivals and themes are also being remembered, revived and celebrated as the Celtic nations of Great Britain and Ireland become more aware of their past shake off imposed English and earlier church led festivals.

The coming of Christianity to the Britain Isles and Ireland especially to Cornwall during ‘The Age of Saints’ during the 5th to 6th centuries saw many of the ancient pagan places of worship, ritual importance and customs absorbed into Christianity to help make the transition more acceptable to ordinary folk. Many of these saints originated from Celtic lands, especially Ireland and were of Celtic birth themselves. These saints would have extensive knowledge of Celtic traditions, rituals and feast days.

Of the ancient Celtic festivals probably the best known are Samhain held on October 31st and Beltane on May 1st. Many people today would have celebrated Samhain, mostly perhaps as part of the Christian celebration of Halloween but increasingly Samhain itself. As more people rediscover their Celtic roots celebrating Samhain is again becoming better known and more popular.

Halloween is an abbreviation of ‘All Hallows’ Evening’ which encompasses All Saints’ Day and All Souls’. The word hallow itself rarely used these days, in the Lord’s Prayer and in the bible and means to venerate, make holy or saintly. This is the start of the festival when historically the church laid down a period to remember the saints, martyrs and faithful Christian dead. Originally believed to have started around 610 and established on 31st October by Pope Gregory III around 731, originally being held on 1st May. The 31st October was to earlier Christians one of the most holy days of the year. They would be spinning in their graves to see how this significant Christian remembrance festival has evolved for many people into the Americanised and commercialised event it is today.

In ancient pre-Christian times Samhain would have included appeasement to the deities and gods worshiped to help ensure survival of family and livestock through the winter. Food was offered and ancestors remembered and visiting souls offered hospitality. It also marked the beginning of winter when the livestock such as cattle, sheep and goats were brought within buildings often for the poor the ground floor or other part of the family home

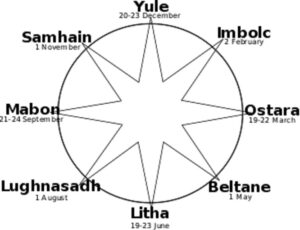

Celtic traditions that include what has become known as the Wheel of the Year marked four solar events Winter Solstice, Spring Equinox, Summer Solstice and the Autumn Equinox. They also marked four seasonal events by celebrating dates of significant seasonal change, one of which is Samhain. This was believed to have been the most significant, hence perhaps why it was appropriated by the medieval church to celebrate similar beliefs of remembering those that had gone before. Samhain marks the beginning of the cycle of the wheel and what has been referred to as a sort of New Year’s Day. Although looking at what we today would consider sad events there was a belief in regeneration of the soul.

Samhain was a time when it was believed that the veil between those alive and the dead was at its thinnest, allowing those souls to pass through to the land of the living. Hence the pleasure that our ancestors would have had in welcoming their own ancestors, and more immediate family that had passed on to their table on Samhain with their feasting. Perhaps others who had passed the portal may have not been so welcome and it is believed that the tradition of guizing or wearing some form of mask or disguise originated from not wanting to be recognised by that soul or spirit.

Archaeology tells us through ancient burial sites that times such as mid-summer, mid-winter and the equinoxes as with stone circles, such as Stonehenge, were recognised in rituals. Also, burial finds within ancient settlement houses illustrate that perhaps favoured ancestors were valued beyond their death. Ancient burials made with far older bones added, as carbon dating of those unearthed, have been found. These archaeological finds help support thinking that the dead along with times of the year were important to our ancient ancestors, perhaps far further back than even our Celtic times.

Many of today’s Samhain celebrations hark back to medieval times, when distant passed down memories of pre-Christian Celtic celebrations were remembered, especially in the Celtic nations. Those were times when mummers and guizer’s were a great part of many festivals. Many of the old stories told in Cornwall mention mummers, unprofessional actors, and guize dancers and certainly the stories collected and published by William Bottrell in the 1870’s make many mentions of them. His book ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’ describes guize dancers as follows:

‘During the early part of the last century the costume of the guize dancers often consisted of such antique finery as would now raise envy in the heart of a collector. The chief glory of the men lay in their cocked hats which were surmounted with plumes and decked with streamers and ribbons. The girls were no less magnificently attired with steeple crowned hats, stiff bodied gowns, bag skirts or trains and ruffles hanging from their elbows.’

There should have been held last week, during normal times, the exciting Lowender Peran Celtic Festival that has been held in Newquay during recent years. Last year’s Samhain celebrations provide some idea of how these events may have been celebrated in the historic past. Music, dance and people participating in disguise along with fantasy beasts.

Although a relatively new Cornish festival since 2007 the Penzance Montol festival held on 21st December is one that marks the ancient Celtic festival of mid-winter. More recently called Yule, from the Old English so not a Celtic word, Montol was held to mean winter solstice by Edward Lhuyd, the famous Celtic language scholar, in his 1700 vocabulary of the Cornish language. This date of course has been used by the early church to celebrate the feast of St Thomas the Apostle marking the date of his death. This year there will be an online event please see www.facebook.com/montolfestival for details

During this festival there are large guizer processions throughout Penzance wearing traditional costumes, masks and carrying lanterns. Although relatively new this festival borrow much from not just medieval times, but also Celtic roots. The renowned Cornish historian A K Hamilton Jenkin who wrote much about Cornwall, its traditions and customs in several volumes certainly makes much of this type of festival with reference to them as early as 1831.

The increase in Celtic studies and on a lighter vein Celtic related fiction has also encouraged the growth of interest in historic Celtic subjects. In the case of Ireland, recent authors such as Caiseal Mór have inspired many to research and learn about legendary stories of the Fir Bolg and fairy folk the Tautha De Danaan. There are many references to the feast days. The same is true here in Cornwall where authors, story collectors and storytellers going back centuries, including William Bottrell have inspired interest in our own folk tales and Celtic based interests, with increasing numbers of well researched books sharing these being published.

![Lowender Peran 2019 [7] Lowender Peran 2019](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lowender-Peran-2019-7-300x169.jpg)

![Lowender Peran 2019 [4] Lowender Peran 2019](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lowender-Peran-2019-4-300x169.jpg)

![Montol Festival Penzance [2] Montol Festival Penzance](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Montol-Festival-Penzance-2-300x199.jpg)

![[19] Voice - Ertach Kernow-041120A - Samhain Celtic Festivals [S] Ertach Kernow - In touch with our Celtic Festivals](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/19-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-041120A-Samhain-Celtic-Festivals-S-234x300.jpg)

![[19] Voice - Ertach Kernow-041120B - Samhain Celtic Festivals [S] Ertach Kernow - In touch with our Celtic Festivals](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/19-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-041120B-Samhain-Celtic-Festivals-S-230x300.jpg)