Ertach Kernow - Cornwall in the Hungry Forties

Ertach Kernow looks at Cornwall in the hungry forties of the 19th century.

Times financially tough for many people and the lengthening war in Ukraine, considered the breadbasket of Europe, has exacerbated the situation further. Looking back in time to another age completely, the inflation was not so much an issue as the cost and availability of food. Many of us were taught about the potato famine in Ireland, where over a million people died, but less about what the situation was in our own homeland of Cornwall. It was a time in the 19th century known as the ‘Hungry Forties’ when all the Celtic nations of the United Kingdom were severely under the English cosh. Although not as acute as the situation in Ireland, Scotland was in the throes of the second Highland Clearances and the start of the Highland Potato Famine. It has been estimated that a third of the population of the western Scottish Highlands emigrated in the two decades following 1841.

Mention of Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, the man who contributed to countless deaths in Ireland, will still raise hackles there. The historian Cecil Blanche Woodham-Smith, author of The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849, was highly critical of him and the British government. Trevelyan wrote in a letter to an Irish peer ‘the judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson’. To the Chancellor of the Exchequer Trevelyan wrote ‘The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people’.

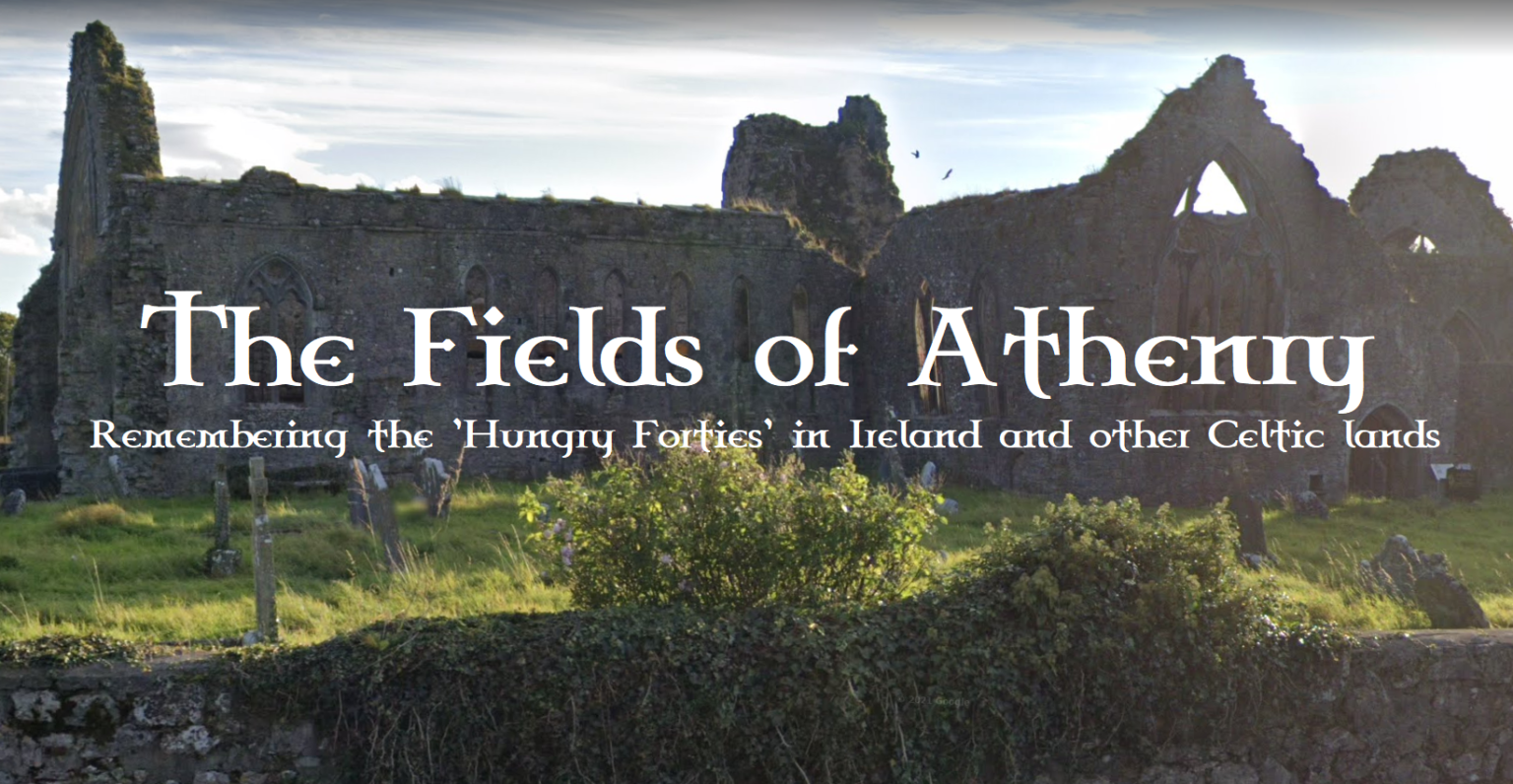

Trevelyan as his name might suggest came from an ancient Cornish family that originated in the parish of St Veep. Not only was he instrumental in not assisting and preventing help to those in need during the famines, but his family derived their wealth from slave owning in Granada. He is famously remembered in the sad, but beautiful Irish ballad memorialising the Irish famine, ‘The Fields of Athenry’, in the lines where Mary sings of Michael ‘For you stole Trevelyan's corn, So the young might see the morn’. Trevelyan never showed any regret for his actions. The staple food for poor Irish families was the potato, the harvest of which was devastated by the blight with meat and grain exported in large amounts to England. Is it no wonder how Trevelyan and the inaction of the British government for the benefit of England is so resented nearly two hundred years later including in those places which benefited from the mass exodus of people from Ireland, Scotland and Cornwall.

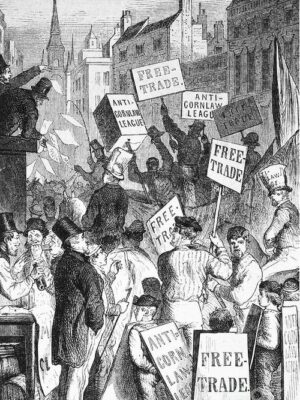

Cornwall at this time was starting to see the beginning of a decline in its mining industry, especially copper and tin. Although food was available it came at increased costs, and lack of money saw many Cornish families starving. Cornwall was and is still one of the poorest areas of Britain and the potato blight, causing the Irish Potato Famine, also had an effect here in Cornwall on this staple food for the poor. The early nineteenth century Napoleonic War saw Britain’s trade with Europe almost at a standstill, with little European corn entering British ports. Imports remained low after the war ended in 1815 due to the introduction of the Corn Laws that year with high duties imposed as a safeguard to keep prices high. These tariffs on imported food raised the price for Britain and Ireland making it impossible to buy from abroad even when food supplies suffered. Because of this corn was scarce and expensive in Cornwall as elsewhere the poor suffered intensely.

Rioting mobs on the brink of starvation weren’t uncommon in parts of Cornwall, frequently trying to prevent ships loading corn destined for English markets to fetch higher prices. To help offset this shortage of grain more land was brought into cultivation to grow potatoes. These formed the main crop for poor Cornish families as potatoes gave the heaviest yield yard for yard and could be stored to last through the winter. Potatoes or at least the waste ones which grew rotten and unfit to eat could be fed to pigs which most families reared and were an important contribution to Cornish families diet. When potatoes weren’t often available during winter months, pigs were fed boiled elm leaves. When pigs were slaughtered each carcase was scalded, and then salted in brine contained in vast tubs or slate troughs to keep them edible for the future. At some later date unused pork may need to have been re-salted to maintain it further.

1847 was the peak of the food rioting in Cornwall, due to food scarcity or prices. In January one hundred troops were sent from Plymouth and Devonport to Cornwall to suppress rioting miners and the small troop detachment at Pendennis Castle was reinforced in anticipation of trouble. The situation gradually worsened and by May even the coastguard were being used to help quash rioting crowds. 20th May saw upwards of 400 quarrymen from Delabole surround the corn store at Wadebridge demanding sale of corn at the prices they were willing to pay. Many left after they were appeased by being given bread and shown the quantity of corn was not as great as they had thought. However, more miners arrived swelling the crowd to over 700 and with reports of a further 800 miners joining them from the west magistrates sent to Plymouth for troops to reinforce the fully armed coastguard. The crowd was eventually dispersed after receiving refreshments and later the soldiers arrived, remaining for some days. A similar situation was reported at Callington where over 200 miners compelled owners of corn to sell it at the prices they were willing to pay. Besides the men many wives joined in and taking over the Callington butter market to obtain butter at the prices they demanded. Many farmers bringing their stock to market on hearing of the situation turned tail and returned home for fear of losing their produce. Similar stories were told relating to marauding miners in Liskeard and Camelford.

Fortunately, many understood the position of the miners and the disparity between the exorbitant prices of food and low wages, this helped alleviate distress which led to rioting elsewhere and calming the situation. St Austell avoided much unpleasantness due to a proactive approach by the Cornish entrepreneur J T Treffry, the controlling owner of both Fowey and Par Consols. On 14th May handbills were distributed offering subsidised flour, wheat and barley to all miners whose earnings were insufficient to cover their family’s needs by means of a ticket system. At Newquay a subscription raised funds to help the poor by purchasing corn in Liverpool and shipping it in. Likewise, a charitable approach by Mr Mitchell at the East Wheal Rose Mine led to him chartering a ship in Liverpool and bringing in supplies to be sold at reduced prices. Other mines throughout Cornwall including Wheal Vor, Wheal Rose, Wheal Ruby and Levant Mine also bought grain and flour for their workers, often selling this below their purchase price. There were sadly reports of wealthy farmers who continued to profiteer and unwilling to sell below the extortionate prices they requested.

On 4th June a large crowd of about 3,000 people at Pool were incited by three women to break into a corn factors store, as he had been unwilling to lower his prices. They carried off sacks of flour, tea, coffee and other articles it would appear there was then a free for all as the whole store was plundered for anything and everything that could be carried away. A magistrate read the Riot Act and sent for troops from the 5th Fusiliers who had been stationed at Penzance. The crowd then moved onto Redruth where once again the magistrate read the Riot Act. This did not prevent all manner of retailers and dealers, such as butchers, being threatened to sell their provisions at ruinous prices to the rioters. To help prevent use of firearms by troops the rioters placed women and children in the forefront of the crowd, but fortunately troops did not have to fire on the crowd, which later dispersed into the evening.

Shortly after the rioting prices started to drop back to normal levels, due to large amounts of corn being imported from the United States. Many merchants went bankrupt having to sell their corn obtained locally and from England at a loss. 1847 was the worse year for peak prices causing the food crisis in Cornwall. Following the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 increased import of grain at reduced prices without tariffs gradually took effect.

The Cornish Diaspora around the world counts many millions of people who descend from Cornish emigrees. Many Cornish families, including my own, will have stories of family members who emigrated from Cornwall to other parts of Britain as well as further afield around the world. Hunger and lack of work were the major contributors, and this would continue in large numbers into the early decades of the twentieth century.

Mentioned in this article is the sad, but beautiful Irish ballad 'The Fields of Athenry written by Pete St John in 1979 and memorialising the tragedy of the Irish famine in song, this is now an Irish anthem. As one of the most popular songs in Ireland it is often heard in sports stadiums sung by Irish supporters when Irish teams play international games.

This can be viewed along with the lyrics on our YouTube Channel. The lyrics and musical score can be downloaded here.

![[100] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 25.05.22A The Hungry Forties [S] Ertach Kernow - The Hungry Forties](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/100-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-25.05.22A-The-Hungry-Forties-S-240x300.jpg)

![[100] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 25.05.22B The Hungry Forties [S] Ertach Kernow - The Hungry Forties](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/100-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-25.05.22B-The-Hungry-Forties-S-241x300.jpg)

![[100] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 25th Month 2022 - Out and about & keeping alive our traditions Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 25th May 2022 - Out and about & keeping alive our traditions](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/100-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-25th-Month-2022-Out-and-about-keeping-alive-our-traditions-274x300.png)