Ertach Kernow - Cornwall in 1841 how we used to work

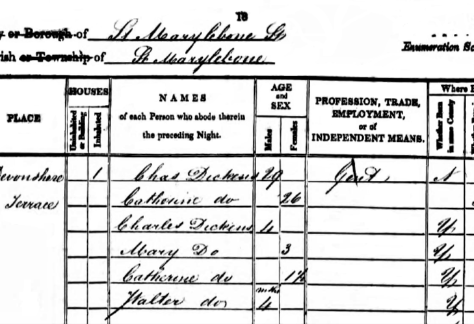

Cornwall in 1841 how we used to work - Statistics are a part of our lives these days measuring everything for planning, management and inevitably taxation purposes. This involves collection of information and as readers of this column know we often refer back to the 1086 Domesday Book of William the Conqueror. Looking back just 221 years to the beginning of census records in 1801 these have created a wonderful collection of information about life over this period and a treasure trove for academic and family history researchers. Although there had been four census enumerations between 1801 and 1831 these only included numbers and useful for purely statistical purposes. The 6th June 1841 was an important date especially for those studying family and social history, this was the date that the first census took place that included people’s names.

For the first time there were names, employment information, approximate ages and whether born in Cornwall or elsewhere. The Population Act 1840 adopted a completely different procedure operating under central governmental control rather than information collection on a local parish level. This model would subsequently gradually add further information including in 1851 marriage status, relationship with the head of the household and importantly where actually born. There was also a column asking whether the person was blind, deaf or dumb and by 1911 would also ask whether the person was a lunatic, imbecile or feeble minded.

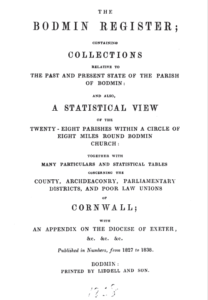

There was also the small but informative The Cornwall Register, published in 1847, which although primarily Bodmin based covered certain statistics for the whole of Cornwall. It broke down the population numbers by parish and also includes tithe records as collected due to The Tithe Commutation Act, 1836. The maps and information provided through this act have been of immense interest especially to local historians. Originally published in numbers between 1827 and 1838 by Liddell and Son of Bodmin, as The Bodmin Register, it covered the past and present state of the Parish of Bodmin along with the 28 parishes within a circle of eight miles around Bodmin’s church.

In 1841 the population of Cornwall stood at 341,279 against a population today of around 568,000. Whilst the population reached a 19th century peak of 369,390 in 1861 this dropped back through emigration to 317,968 by 1931. There have been large rises since 1961 when the population returned to approximately its 1841 level at 342,301 residents. Since 1961 over a sixty-year period Cornwall’s population has risen by around 226,000.

Looking around parts of Cornwall today there seem to be endless signs recruiting and hiring people for a variety of jobs, many in hospitality. A very worrying trend has emerged as the younger Cornish population has once again been falling against a huge rise in elderly people retiring to Cornwall. Is this again due to emigration due to lack of meaningful jobs for young Cornish workers and the ongoing crisis in housing through second houses, Airbnb and holiday letting? No wonder so many firms are now struggling to find local employees to operate their businesses.

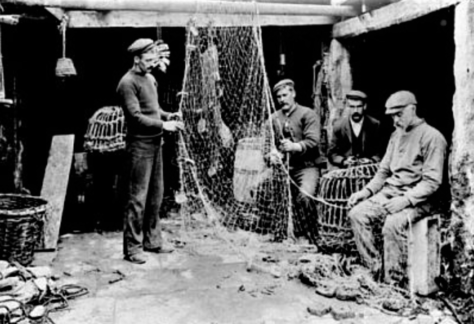

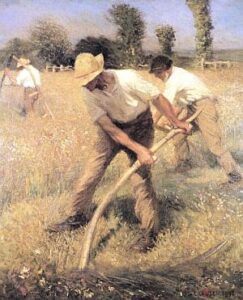

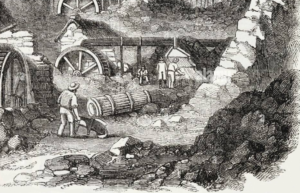

Looking back 180 years, what was the employment situation prior to the exodus of the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Many of the jobs then employing people no longer exist and have been replaced by new late 20th and 21st century occupations. Unsurprisingly the highest employment was found in the mining industry, the workers who actually grafted in extracting the ore totalled nearly 27,000 (23% of the working population) of which marginally over 10% were women. The next highest sector for employment was farming with a total of just over 26,000 workers (22.5% of the working population) of which 5% were women. Adding in those involved in fishing and the maritime trade about 2,086 (2.5%) and all the other ancillary workers to these three trades of farming, fishing and mining some 50% of the working population and their families were reliant on these industries. Is it no wonder that when the mining industry crashed from the mid to late 19th century there was so much emigration looking for work beyond Cornwall’s borders.

In the days before all the domestic whitegoods we have now to carry out our household tasks, the third highest employment was as domestic servants. There were just over twenty thousand (18%) in 1841 including charwomen, part time cleaners. Of these two thirds were women and of the 6,612 males some 4,130 were young men under the age of twenty with sixty one percent of the female servants over the age of 20. Following World War One many women who had found employment replacing men’s jobs during the war did not return to domestic servitude. The introduction of household equipment would in turn dramatically reduce the need for personal domestic servants.

The fourth highest employment sector was in construction with nearly ten thousand workers across many trades. This made up, including the connected professionals such as surveyors and architects, about 10,000 people 9% of the working populations. Of course, in those days there was no health and safety and human resource jobs, which would later help boost employment numbers. Construction today employs some 13,000 workers throughout Cornwall.

Today much of our clothing is produced in factories and workshops elsewhere in the world, often bought online. In 1841 the sector producing clothing, the cloth used to make them, including boot and shoemakers, employed about 9,000 workers, about 8% of Cornwall’s working population. This was the fifth largest grouping and included traders in cloth and leather. Retail of all types made up about 1,500 people with a further 800 in taverns, inns and hotels as owners and workers, occupations we would now term as hospitality.

We complain today about access to a dentist, doctor or other medical facilities. In 1841 there were a total of only three men reporting in Cornwall’s census as dentists and thirteen as physicians, with six midwives. Now days I would expect to see few if any manufacturers of matches, naptha, sieves, and stays & corsets, but you never know, and it would be interesting to know how many old skills are still maintained and not lost entirely.

Looking back at the employment of two of my great-grandfathers their jobs have virtually disappeared or become very niche. In 1841 there were in Cornwall 206 saddle and harness makers and 15 brush and broom makers. I suspect the numbers of blacksmiths, smiths and farriers has now declined dramatically from the 1841 census numbers when there were approximate 2,500. With a change of focus there will be a number of smiths now working within Cornwall’s creative community on precious and semi-precious metals with work still available for far fewer blacksmiths and farriers.

There were in 1841 as now homelessness and people living in less than satisfactory circumstances. These consisted of 139 persons in barns, tents, and caravans and 237 in boats and barges. Those categorised as alms people, pensioners, paupers and beggars including those in the poor houses totalled 3,090. There were also 19 residing in a nunnery, 140 in lunatic asylums and 119 in gaol.

Today Cornwall has 253,800 economically active people in all employment, 45% of the population, against 115,600, 34% in 1841. The increase in employment levels despite automation and the loss of all those domestic jobs and collapse of the mining industry has occurred through women actively entering the job market and creation of new industries and employment opportunities. Education amounted to under 1,000 jobs in 1841 now it’s around 20,000, with hospitality now totalling 31,000 against just 800 before the railways initiated the tourism boom. The improvement in health and social services has led to employment of 32,000 (15.2%) against virtually none in 1841. The loss of the mining industry, which besides employment also created wealth was a blow somewhat offset by tourism. However, Cornwall’s farming industry has remained robust with agriculture, forestry and fishing remaining the largest industry group with 15% of businesses. Employment number have dropped by an estimated 50%, but productivity through mechanisation and improved farming methods has increased output substantially. This is followed by construction at 12%, no surprises there, with retail and hospitality with about 10% apiece.

As we entered the post war boom Cornwall’s industrial past has become, through tourism and greater leisure time its future, with increased numbers employed across the heritage sector. Many of the tourists visiting Cornwall from around the world, come through interest in their own family history as they visit places from which their ancestors emigrated, looking for work, during the later 19th century.

A final note from the 1841 census report is positive for Cornwall and Devon and relates to the health of our peoples. ‘It may be worth noticing that it is in the maritime counties that we find the least comparative mortality’. Statistics showing mortality rates for every 10,000 inhabitants was in Cornwall 180 and Devon 179, the average of England being 221. It concludes, ‘May it not be inferred from this that the comparatively large exposure to sea- air of this island may have contributed with other causes to lower its average rate of mortality as compared with other countries.’

For those interested in starting family history research, a series of workshops will begin initially at Newquay Museum, but also elsewhere subject to demand. Please email associationcornishheritage@gmail.com for more information.

![[102] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 08.06.22A How we used to work [S] Ertach Kernow - How we used to work](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/102-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-08.06.22A-How-we-used-to-work-S-244x300.jpg)

![[102] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 08.06.22B How we used to work [S] Ertach Kernow - How we used to work](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/102-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-08.06.22B-How-we-used-to-work-S-241x300.jpg)

![[102] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 8th June 2022 - Preserving & Protecting Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 8th June 2022 - Preserving & Protecting](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/102-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-8th-June-2022-Preserving-Protecting-276x300.png)