Ertach Kernow - Cornwall and Brittany Celtic cousins

Cornwall and Brittany are Celtic cousins and as similar nations may have benefited from a surge in people travelling abroad following the difficulties over the past couple of years due to the pandemic. Hopefully many will have visited some of our Celtic neighbours. The Celtic languages encompassing six nations are of two branches the Goidelic and the Brythonic the latter being Cornish, Welsh and Breton. Although these languages have diversified over the past several hundred years there are similarities and a degree of understanding between languages within each of the two branches.

Professor Sir Barry Cunliffe has written about the spread of Celtic culture especially relating to language up the Atlantic seaboard based on an early proto-Celtic language. This language split from neighbouring Indo-European languages about 4,000 BCE, with a further split in the Celtic language believed to have taken place at the time of the Bronze Age to Iron Age advance. A final divergence around 650 BCE let to the separation of the Goidelic and Brythonic Celtic language branches. It seems that Brittany shared the same language as the whole of what would become England, Wales and Cornwall from that time, through to the English Anglo-Saxon incursions leading it to be pushed ultimately westwards through to Cornwall and Wales. Much work has been carried out on Celtic studies in recent years by linguists, archaeologist and geneticists including identification of words from the earliest times of the Celtic languages. Many have been reformulated proving their common ancestry.

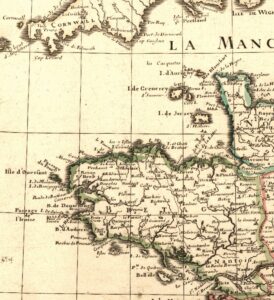

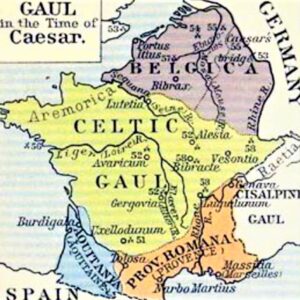

Looking across the sea to the European mainland. What is now France, parts of Germany, and the Benelux nations were known as Gaul during the time of the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar wrote extensively about his campaigns there during the first century BCE. With the defeat of Celtic leader Vercingetorix in 52 BCE the whole of Gaul effectively became part of the Roman Empire, which included the region that would in time become Brittany. This was known at the time as Amorica and was inhabited by peoples who we would now identify culturally as Celtic. Whilst the Gaulist Celtic language was lost at the time of the Romans it continued in Brittany.

With the fall of the Roman Empire and loss of influence on Amorica early in the 5th century the region reverted back to its Celtic pre-Roman state. There then followed a large immigration to Amorica from Cornwall along with Wales. Repercussions from the growth of the new Anglo-Saxon nations due to invasion by Angles, Saxons Jutes and Friesians gradually obliterated Celtic culture as their new kingdoms proliferated in what would later become England. Cornwall and part of what is now southwest England retained independence for a further two to three hundred years. The late 5th and early 6th centuries is believed to have been the period of King Arthur, or a leader such as him, leading the Britons in defence of Britain. He is said to have travelled back and forth between Cornwall and Amorica during this period. The commonality between Cornwall and Brittany relating to legends in particular those of King Arthur are greater than elsewhere. Geoffrey of Monmouth's 'History of the Kings of Britain' (c113S) has Arthur defeating the Saxons with his chief allies the Bretons. There is also similarity in legends relating to the sunken lands of Lyonesse, which abound in both nations.

So, what of the similarities Brittany has with Cornwall relating to its ancient monuments. For that we need to look to a far earlier age than the Romans or even the Celts. Brittany has one of the greatest array of monuments at Carnac of anywhere in the world. However, many of the features of monuments found in Brittany can be found here in Cornwall on a much smaller scale. There is some archaeological discussion regarding the dating of these monuments between the Mesolithic hunter gatherer period and the later Neolithic farming era of the Stone Age. The movement of people during the early part of the Neolithic where farming methods moved across Europe eventually reaching Brittany and where the next step would have been across the sea to Cornwall and Britain.

The early Celtic church during what has become known as the Age of the Saints involved many people now known as saints travelling between the Celtic nations and England. Many of these travelled to and from Brittany and Cornwall and as such many became revered in both nations. One of the earliest for which documentary evidence exists is St Samson of Dol, who originated from Wales, and has the distinction of being the only Cornish saint whose biography was written within two hundred years of his death. St Samson is associated with at least two Cornish churches at Golant and South Hill near Callington. South Hill has a Christian inscribed stone dated to the 6th century and archaeological work has confirmed an earlier Norman church and cist cemetery on the site. This points to an early settlement helping confirm belief that this settlement was associated with St Samson. He is also referenced as passing through the Docco monastery at St Kew and continuing his travels through Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Guernsey finally arriving in Brittany. There he founded the monastery at Dol, hence becoming known as St Samson of Dol, where he died in 565 and was buried there in the cathedral.

As we look back on sites such as Carnac perhaps future generations far into the future will look at the remains at Carnoët in Brittany of statues of Breton saints. These are being carved from Breton granite and represent the many saints who travelled to Brittany during the Age of Saints. There are those connected to Cornwall especially the statue of our own national patron saint, St Piran. There are presently over 160 statues erected with many more planned and in the process of being sculpted.

The statue of St Piran is the only one not to have been carved from Breton granite, the statue was carved from Cornish granite from Trenoweth quarry near Mabe in Cornwall, the millstone from Irish granite and only the base from Brittany. After being carved in Cornwall by sculptors David Paton a Cornishman and Breton Stephane Rouget the statue left Cornwall in May 2018 and was erected at Carnoet on 28th July. It stands on a hillside facing Cornwall, a fine example of commemorating three Celtic nations in stone. St Piran was the one hundredth statue erected and there was much celebration with many visitors from Cornwall, including a delegation from Gorsedh Kernow and Breton Gorsedd hosts.

Of course, St Samson of Dol is represented, one of the first seven erected in 2009, he being one of the seven founding saints of Brittany. Other Cornish connections by way of statues are those for St Nolwenn (2014), St Tudy (2014) and St Divy has his statue carved from Cornish granite (2019)

There has been longstanding interaction and friendship between Cornish and Breton fishing communities from the beginning of the 20th century. Hopefully issues relating to Brexit won’t ruin those connections. Breton fishermen were regular visitors to Cornish harbours including those in the Isles of Scilly, Newlyn, St Ives, Padstow and Newquay. Past Grand Bard of Gorsedh Kernow and BBC Radio Cornwall Cornish language newsreader Rod Lyon, in an interview with former BBC broadcaster Chris Blount, talked about his beginnings in speaking the Cornish language. Newquay is where Rod grew up and he spent much time in and around Newquay Harbour. Kernewek was not much spoken in Cornwall during his youth, and it was whilst working on a Breton fishing boat he learned to speak some Breton, which encouraged him to later learn Cornish becoming a fluent Kernewek speaker.

Close contact between the Brittany and Cornwall still remain today with some 36 Cornish towns with twinning agreements between the two communities, along with many common artistic & cultural projects. Something to consider, perhaps an historic coincidence relate to the flags of Brittany and Cornwall. The Baner Sen Peren of Cornwall being a white cross on a black background, mentioned by Gilbert Davies in 1835, has a long history even further back in time than Davies’ writing. The current flag of Brittany known as the Gwenn ha Du (Gwynn ha Du in Kernewek) was designed in 1923. However, the historic Ducal flag of Brittany until the 16th century was the Kroaz Du, an exact negative of the Baner Sen Peren being a black cross on a white background. The Kroaz Du is now increasingly seen during Breton demonstrations and protest marches than in the past, especially those relating to Breton language issues with the French government. There has been progressively more nationalistic pride and calls for greater independence across both Cornwall and Brittany in recent years as well as with other Celtic nations.

![[115] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 070922A Celtic Cousins [S] Ertach Kernow - Celtic Cousins](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/115-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-070922A-Celtic-Cousins-S-240x300.jpg)

![[115] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 070922B Celtic Cousins [S] Ertach Kernow - Celtic Cousins](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/115-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-070922B-Celtic-Cousins-S-238x300.jpg)

![[115] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 7th September 2022 - Cornwall's Heritage Open Days Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 7th September 2022 - Cornwall's Heritage Open Days](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/115-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-7th-September-2022-Cornwalls-Heritage-Open-Days-254x300.jpg)