Ertach Kernow - Cornish myths and legends collected and told

Recently watching Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, for research purposes of course, I saw the fantasy of Cornish Pixies running riot and being immobilised with the spell ‘Immobulus’.

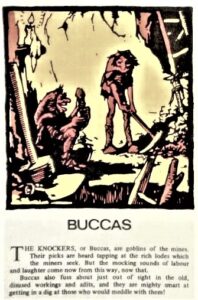

Pixies or better known here as piskies, fairies and such like have been a part of Cornish folklore since time immemorial and are a common theme running through the legends and myths of the Celtic nations. During the pre-Christian era, Celtic people worshipped a wide range of gods and goddesses who were often later reduced and subsumed into what have often been referred to as the little people by writers and the church. Ireland for example has its range Leprechauns, Clurichaun, Changelings, Banshees and others. There are also the ‘Tuatha Dé Danann’ were recorded from Irish mythology by medieval monks variously as gods, immortals or fallen angels. Besides the ‘small folk’ in Cornwall there are also tales of giants, witches and other sorcery including that concerning Arthur Pendragon, Merlin and Morganna le Fay. Also, how stone circles came to be, transformed from people by divine saintly intervention.

The word folklore came into being in 1846 when William Thoms created the term to encompass a range of popular traditions and study of these, that included many of the stories told and enjoyed by ordinary people.

There was increased interest in Cornish folklore and the various branches of faerie in the 19th century by writers including Robert Hunt, William Bottrell, Margaret Courtney, and the Reverend W S Lach-Szyrma. These writers tried to categorise these beings into groups, none of them seemed to agree with each other. Even the great Henry Jenner founder of the Old Cornwall movement, Gorsedh Kernow and campaigner for Celtic Congress Cornwall waded into the fairy morass. Jenner provided an introduction to the Cornish section of The ‘Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ by W. Y. Evans-Wentz published in 1911. This book was published over one hundred years ago, and many more modern volumes have succeeded it. However, it was written from interviews taken at a time when many of the stories were still believed by the interviewees or their parents.

A term that is not commonly heard now is that of droll and was common in the seventeenth century for entertainments, plays and suchlike. The term droll-teller seems only to have ever been used in Cornwall and up to the early 19th century these storytellers roamed Cornwall telling stories and entertaining people. Many of these would have told their stories in Kernewek and perhaps it was the reduction in use of the Cornish language that eventually diminished them.

Enter Robert Hunt, who we must excuse the need to categorise, his primary occupation being a mineralogist and scientist. What he began to do was to collect the old stories from throughout Cornwall wanting to ensure that they were preserved and not lost and to gather every fragment. He received contributions from William Bottrell, Thomas Quiller Couch and countless others, publishing ‘Popular Romances of the West of England or the Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall’ in 1865. He was the first person to actively collect Cornish folklore stories. In 1829 he spent ten months travelling around Cornwall trying to gather up ‘every existing tale of its ancient people’. One story collected was not an ancient story but of a droll-teller who was remembered by one of his interviewees and perhaps gives us an idea of how these travelling storytellers lived and worked.

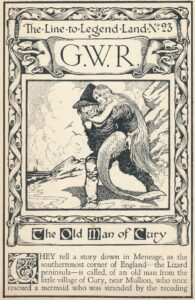

‘The only wandering droll-teller whom I well remember was an old blind man, from the parish of Cury, — I think, as he used to tell many stories about the clever doings of the conjurer Luty of that place, and by that means procure the conjurer much practice from the people of the west. The old man had been a soldier in his youth and had a small pension at the time he went over the country, accompanied by a boy and dog. He neither begged nor offered anything for sale but was sure of a welcome to bed and board in every house he called at. He would seldom stop in the same house more than one night, not because he had exhausted his stories, or ‘eaten his welcome,’ but because it required all his time to visit his acquaintances, once in the year. The old man was called Uncle Anthony James… Uncle Anthony James used to arrive every year in Leven parish about the end of August. Soon as he reached my father’s house, he would stretch himself out on a chimney-stool and sleep until supper-time. When the old man had finished his frugal meal of bread he would tune his fiddle and ask if ‘missus’ would hear him sing her favourite ballad.’

William Botterell who had been collecting stories for many decades would go on in time to write and publish his own books relating to Cornish tales. ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’ was published in 1870 with two further volumes in 1873 and 1880. Margaret Courtney would go on to publish ‘Cornish Feasts and Folk-lore’ in 1890. Many of these stories were based on her writings published by the Folklore Society in 1886 and 1887. Courtney would also write about Cornish dialect in 1880.

Other writers would emerge during the 20th century, but most of the collecting of ancient stories and evidence was over. Many books would concentrate on analysing and the retelling of stories in a modern context to encourage continued interest in the old stories. Recently authors such as Alex Langstone would produce books such as those based on an area of Cornwall including ‘From Granite to Sea – The Folklore of Bodmin Moor and East Cornwall’ Cheryl Straffon’s ‘Between the Realms Cornish Myth and Magic’ is an interesting read. The late and much missed Craig Weatherhill also entered into sharing ancient stories in ‘Myths and Legends of Cornwall’ co-written with Paul Devereaux.

To watch a story video from Mike O'Connor & Yvonne White click the Cornish Folk Tales book image. Recorded for the Newquay St Piran's Virtual Festival 2021, storytelling is alive and well in the 21st century.

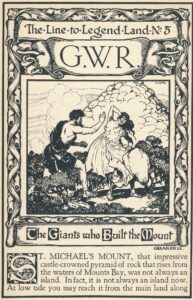

Folklore has been rich pickings for the tourism industry, so much so that the term fakelore came into being during the 1960’s. As far as Cornish folklore is concerned, the imposition of folklore that has been altered to meet an agenda by organisations outside Cornwall has certainly benefited the tourist industry as they sell their products. These might be travel as with the Great Western Railway, postcards with appalling dialect or images of piskies or the forceful sharing of the Arthurian legends at Tintagel, still lapped up as the truth by many of today’s gullible visitors.

The Great Western Railway certainly exploited Cornwall’s folklore and even coastal outline to sell their train journeys and holidays during the early 20th century. The poster showing Cornwall compared to Italy and the national costumes were fanciful, the map perhaps inspired by the 1802 Neele & Wilkes map of Cornwall. A series of pamphlets published in the 1920’s entitled ‘The Line to Legend Land’ provided a hugely abridged version of the folktale but always finding space to promote places and trips that could be reached by train, along with a railway line map.

For those that may want to dip into reading some of Cornwall’s more authentic and historic well-loved stories, Robert Hunt’s collections are still being published today often modern writers adding historical context make this an interesting subject to explore and stories to perhaps share with children.

![The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries - Signed Title Page [1] The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries - Signed Title page](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-Fairy-Faith-in-Celtic-Countries-Signed-Title-Page-1-193x300.jpg)

![[43] Voice - Ertach Kernow-210421A - Exploring the land of legend [S] Ertach Kernow -Exploring the land of legend](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/43-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-210421A-Exploring-the-land-of-legend-S-233x300.jpg)

![[43] Voice - Ertach Kernow-210421B - Exploring the land of legend [S] Ertach Kernow -Exploring the land of legend](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/43-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-210421B-Exploring-the-land-of-legend-S-232x300.jpg)