Ertach Kernow - Feisty travels with Celia Fiennes in Cornwall

Throughout this series of articles, we have included the travels of various people throughout Cornwall since the 16th century. Mention has been made of the poor roads throughout Cornwall until well into the 19th century, this certainly did not deter one intrepid traveller to Cornwall, a feisty and unconventional woman by the name of Celia Fiennes. At the time of Celia’s travels around Cornwall there were no stage-coaches, these would not appear in Cornwall for many decades. Celia’s family was of the Fiennes line of the barons and viscounts Saye and Sele, her brother would become the 3rd Viscount. She enjoyed travel, mostly taken within family groups, but also on horseback with just one or two servants. Between 1684 and about 1703 Celia undertook many trips, including from Newcastle to Cornwall from around 1695. Travel horseback for pleasure was almost unheard of at that time, especially for a woman. What is noteworthy and invaluable about Celia’s diary is the descriptiveness of her journey, the routes, people and the houses she sees and visits during the late 17th century.

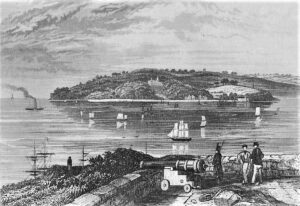

Before entering Cornwall, she described Mount Edgcumbe House before setting off on the the Cremyll Ferry.

‘I saw mount EdgeComb a seate of Sr Richard EdgComes, it stands on the side of a hill all bedeck'd with woods whice are are Divided into several Rowes of trees in walks, the house being all of this white marble. Its built round a Court so the four sides are alike, at ye Corners of it are towers whice with ye Lanthorne or Cupilow in the middle Lookes well, the house is not very Lofty nor the windows high but it Looked Like a very uniforme neate building and pretty Large.’

The interior of the house was destroyed in 1941 and it was rebuilt from 1958. The walls were not marble but stucco and painted white, which they had been since the late 17th century, when Celia saw Mount Edgcumbe.

Travelling mostly in sight of the sea, but sometimes riding along narrow lanes lines with trees she came to Looe where she describes it so; ‘I Crossed a little arm of ye sea on a Bridge of 14 arches. This is a pretty bigg seaport. A Great many Little houses all of stone, and steep hill much worse and 3 tymes as Long as Dean Clapper hill, and soe I continued up and down hill.’ Dean Clapperhill was between Ashburton and Plymouth and was known for the steepness of its road and said of it ‘that even the cleverest moorland pony could not gallop down its lane.’

Celia and her horse were not at all impressed by the roads, having several deep pothole issues, but she continues ‘Soe I came to Hoile (Hall Farm) 8 miles more, they are very Long miles ye ffarther West but you have ye pleasure of Riding as if in a Grove in most places, ye Regular Rowes of trees on Each side ye Roade as if it were an Entrance into some gentlemans Ground to his house.’ Taking the ferry across the River Fowey Celia remarks on the colour of the water as green as she has ever seen and how deep it must be.

Talking about Fowey, Celia comments in her diary. ‘This Hoile is a narrow stony town, ye streetes very Close, and as I descended a Great steep into ye town, soe I ascended one up a stony Long hill farre worse and full of shelves and Rocks and 3 tymes as Long as Dean Clapperhill, which I Name because when I was there they would have frighted me with its terribleness as ye most inaccessible place as Ever was and none Like it, and my opinion is yet it was but one or two steps, to other places forty steps and them with more hazard than this of Dean Clapper.’

Onwards to Par where she took a ferry, although noting that when the tide was out it was fordable. It then transpired what may be one of her most important episodes and the diary notes that benefited Cornwall’s future.

‘Thence I went over the heath to St Austins (St Austell) which is a Little market town where I Lay, but their houses are like Barnes up to ye top of ye house. Here was a pretty good dineing room and Chamber within it and very neate Country women. My Landlady brought me one of ye west Country tarts this was ye first I met which though I had asked for them in many places in Sommerset and Devonshire; its an apple pye with a Custard all on the top, its ye most acceptable entertainment ye Could be made me. They scald their Creame and milk in most parts of those Countrys and so its a sort of Clouted Creame as we Call it, with a Little sugar and soe put on ye top of ye apple Pye.’

Reading this extract from Celia’s diary on how taken she was with apple pie topped with clotted cream, our traditional Cornish clotted cream it seems was appreciated then as much as it is today. Interestingly in the 1993 application to have Cornish Clotted Cream registered as a Protected Designation of Origin in Europe, The Cornish Clotted Cream Producers gave a history of clotted cream production quoting the above section from Celia Fiennes diary. Protection was granted in 1998.

What she wasn’t taken with was the communal smoking of pipes by men, women and children as they sat around the fire at her lodgings. Her landlady was however described as comely and very neate.

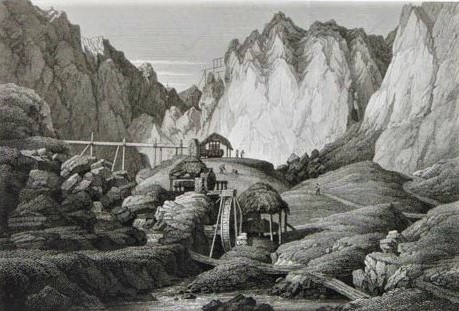

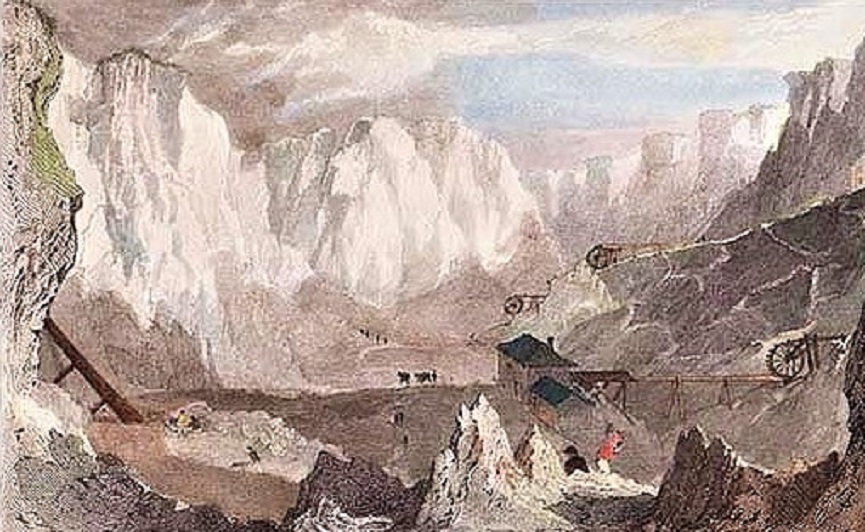

Celia’s diary then provides an interesting description of the processing of tin in the stamping mill and blow house about half a mile from her lodgings in St Austell.

‘They take ye ore and pound- it in a stamping mill which resembles the paper mills, and when its fine as ye finest sand—some of which I saw and took—this they fling into a ffurnace and with it Coale to make the fire. So it burns together and makes a violent heate and fierce flame, the mettle by ye fire being separated from ye Coale and its own Drosse, being heavy falls down to a trench made to receive it at ye furnace hole below. This Liquid mettle I saw them shovel up with an jron shovel and soe pour it into molds in which it Cooles and soe they take it thence in sort of wedges or piggs I think they Call them, its a fine mettle in its first melting—Looks Like silver—I had a piece poured out and made Cold for to take with me. ye oare as its just dug Lookes Like ye thunderstones, a greenish hue full of pendust this seemes to Containe its full description, ye shineing part is white.’

Going a further mile down the road Celia then describes the mining area and how the mines were worked. She was impressed with the size and clarity of quartz crystals ‘as bigg as my two ffists’ claiming they were known as Cornish diamonds. Along with her souvenirs of fine crushed tin ore, a small tin ingot she also obtained a quartz crystal. Was this maybe the first record of Cornish mining souvenirs being taken away by a tourist to Cornwall? Although It’s not named, this would probably been the Carclaze Mine where the tin ore was mixed in with quartz. After being mined exclusively for tin for about 300 years the failure of the tin industry during the 19th century saw Carclaze Mine turning to china clay production, eventually having a lifespan of some 400 years covering both tin and china clay extraction.

Celia then proceeded to her cousins, the Boscawens at Trygothy (Tregothan), providing a description of that house as in 1700, after its first rebuilding. Although the roads are now much improved beyond Celia’s wildest dreams many smaller side roads and lanes still have their treelined routes with mature overarching branches. One thing that remains constant is how much people still enjoy Cornwall’s clotted cream 325 years from Celia’s time. We should show thanks to Celia for her diary entry in helping the Cornish Clotted Cream name registered and protected. A memorial to Celia in Cornwall is perhaps overdue?

![[49] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 020621A Feisty Travels with Celia [S] Ertach Kernow- Feisty Travels with Celia](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/49-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-020621A-Fiesty-Travels-with-Celia-S-230x300.jpg)

![[49] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 020621B Fiesty Travels with Celia [S] Ertach Kernow- Feisty Travels with Celia](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/49-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-020621B-Fiesty-Travels-with-Celia-S-236x300.jpg)