Ertach Kernow - Rise and fall of Botallack, Cornwall's most iconic mine

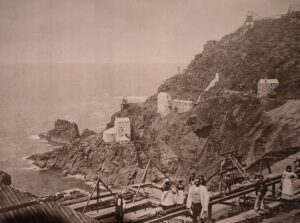

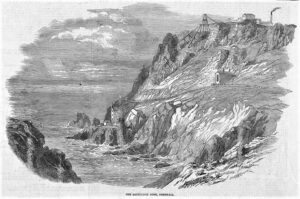

This week 107 years ago one of Cornwall’s most iconic mine working was finally closed. The much photographed and filmed Botallack mine features in the latest Poldark series as Wheal Leisure as well as in the 1970’s series. What is mostly seen is the coastal central Crowns section of the Botallack mine with other shafts and mine workings as part of the mining sett. During the zenith of the mines production there were eleven engine houses besides all widespread tramways, dressing floors and tradesmen’s workshops. Four of the engine houses were perched on the edge of the cliffs and these are what help ensure the romance and memory of the Botallack Mine.

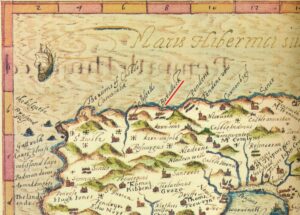

The Botallack area near St Just is one of the oldest areas of tin mining in Cornwall, bar tin streaming which no doubt took place throughout Cornwall for thousands of years back to the Bronze Age. Certainly, there was mining there during the 16th century when John Norden was travelling around Cornwall and England on behalf of Henry VIII. He commented that "Botallack (is)...a little hamlet on the coaste of the Irishe sea, moste visited with Tinners, where they lodge and feed, being nere their mynes. At that time mining was fairly small scale and it wouldn’t be until the early 18th century that greater commercialisation would take place.

Botallack’s earliest deep mine workings date from around 1721, when Lord Falmouth granted a lease to work the land there. The mining sett of Botallack mine is believed to have been made up from several small mines including Wheal Chase, Wheal Cock, Wheal Hazard and Wheal Hen, Zawn a Bal. The total number of shafts going back to 18th century is unknown and many were used later as dumps for mine spoil and are now totally lost.

A compendium of British Mining published in 1843 yields interesting information about Botallack. At that time, it was 900 feet deep and had to date made a profit of £300,000 primarily from tin and was at that time returning a profit of £1,000 per month mostly from copper. It was also out beyond 480 feet from the low water mark and had been so, it stated since, ‘beyond the memory of any person now living’. At some point they had mined too near the surface and broken through, however a timber platform covered with ‘slimy turf and the whole covered by the stony fragments of the beach’ had sealed the breach. The mine was to have been abandoned in 1841 as the tin mined was not economic, fortunately however they discovered rich lodes of copper.

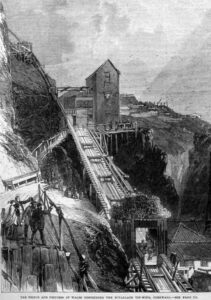

Perhaps because of its romantic location on the cliff edge there was great interest in visitors to Botallack, some of the earliest being French aristocrats followed by children of Queen Victoria including the Prince of Wales and his wife Princess Alexandra in 1865. The writer R M Ballantyne and his wife also visited, and a visitors book was kept at the Count House. Mine visits grew so popular that they started charging visitors. Ballantyne wrote besides well-known novel The Coral Island, Deep Down a story of Cornish mining with a few other tasty Cornish morsels such as smuggling thrown in. Both books have never been out of print and The Coral Island was inspiration behind Newquay born Sir William Golding’s ‘Lord of the Flies’ leading to his Nobel Prize for Literature. Ballantyne spent three months with the miners whilst researching his book, which today is a valuable source of information.

The mining engineer Thomas Spargo, also a stock and share broker, published statistics for Cornish mines in 1864. In a series of publications, we learn that minerals sold in 1864 totalled £31,104 of which Copper ore was £1,380 and black tin £29,724. It seems that further veins of tin ore had been found since 1843. The number of people employed by the mine were 299 men, 116 females and 115 boys, so quite a major employer and important to the local economy. It also looks as if it was a nice earner for the Duchy of Cornwall and the Crown who received one third of dues for minerals mined under the sea. Botallack was by far the richest mine during the years 1862 and 1863 in the Western District of Cornwall with annual productive values of £28,379 and £32,693, respectively.

Spargo it seems was very enthusiastic about Botallack with several pages devoted to this mining enterprise and says; ‘The Botallack Mine is probably the most remarkable in the world. It is so in every way – the surface works in their position and character, the underground operations, the capital employed, and the results.’

His description of the mine workings is useful. Whilst not as deep as Dolcoath it certainly was a feat of engineering. The main shaft extended down 200 fathoms (1,200 feet) perpendicular to the cliffs and at some points were 7 feet high and 4 feet wide and went half a mile under the sea. Spargo compares Botallack with Brunel’s tunnel under the River Thames saying that was incomparable with the marvel that was the Botallack tunnel under the ocean. Spargo also describes the visit of the Prince and Princess of Wales (Duke of Cornwall) and their retinue and how they got down into the mine, although one would wonder why they would wear all white when visiting a mine. I expect Bertie was thrilled especially as he was receiving substantial revenue by way of mineral dues from this mine for the Duchy of Cornwall.

By 1895 the mine was in difficulties. Arsenic was also being produced and this helped offset falling copper and tin extraction. However foreign tin production had pushed tin prices down and extraction was becoming uneconomic. Flooding caused by a cloudburst and other water ingress affected the richest part of the mine and it was decided to close the mine. Some 12 years later an attempt to reopen the mine in 1906 with a new shaft was made, this was not sunk in the best place due to a stipulation by Lord Falmouth, somewhat inland and away from the richest seams under the sea. The new Allen’s shaft was one of the largest (19ft 6” by 6ft) ever sunk in Cornwall but having reached 1,461 feet and 10 levels proved a failure and there was little appetite for investors to continue. As a result, Rodda’s Almanack recorded that on 14th March 1914 Botallack Mine closed.

A footnote to this is that in 1980 Botallack was visited by Queen Elizabeth II and during the mid-1980’s, when tin prices were at an all-time high, Geevor Mines Ltd wanted to expand their workings into the Botallack mining sett. They invested in new headframe and winder over the Allen shaft and the shaft was reconditioned. Sadly, the failure of the International Tin Agreement led to the collapse of tin prices and the project was abandoned.

![Crown engine at Botallack mine in the 1890s [Gibson] Crown engine at Botallack mine in the 1890s [Gibson]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Crown-engine-at-Botallack-mine-in-the-1890s-Gibson-300x214.png)