Ertach Kernow - Ancient Celtic celebrations and artefacts

Ancient Celtic celebrations and artefacts

Seasonal Celtic celebrations and the Lowender Peran Celtic Festival create opportunities to write something about Cornwall’s Celtic identity and to look at the Celtic world retained through our Cornish language and cultural connections. Many in Cornwall especially children would have enjoyed the Halloween celebrations. For those who uphold Celtic interests it would have been the festival of Samhain, when Celts believed the spirit of the land was in the ascendancy and those, we consider mythical beings took the opportunity to ride and frolic on our side of the veil. Samhain is the time of year the veil between the lands of the living and the dead are thinnest and an opportunity to perhaps be in touch with one's ancestors. In the Brythonic Celtic languages, it is also known in Cornwall as Nos Kalan Gwav, in Wales as Nos Galan Gaeaf and Brittany Noz Kalan Goanv. This illustrates the closeness of the languages as well as beliefs where dancing and celebrations take place. In Cornwall this is best observed and participated in at Lowender Peran, which many would have enjoyed recently in Redruth.

Lots of people find it strange that ancient beliefs continue well into the Christian era, but pagan spiritual religions are becoming increasingly popular, so much so that they are being legally recognised. The Druid Network is now a registered charity aiming to inform, inspire and facilitate Druidry as a religion with the same acknowledged status as other faiths such as Christianity and Islam. Most druidic pagan religions focus on nature and the environment embracing spiritual elements, which especially resonates with those wanting to preserve the natural world.

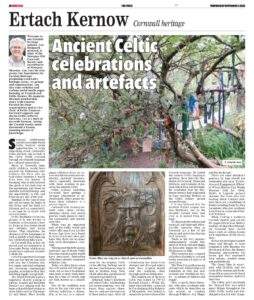

Celtic nations, including Cornwall, have perhaps a stronger attachment to ancient beliefs, where people embrace these religions to a greater degree. Cornwall with its many ancient sites, stone circles, standing stones and quoits provide ready places to carry out ceremonies and similar activities. Water was an important part of the Celtic world and votive offerings from the late Bronze Age have been found in many rivers and lakes, perhaps why there are so many holy wells throughout Cornwall. Throughout the 5th and 6th century Age of Saints Celtic Christian missionaries would have associated themselves with these already venerated religious sites. Today we often throw coins into a fountain and whisper a wish, but on more traditional sites such as holy wells there may be a tree on which rags are tied, known as a cloutie tree. One of the traditions says that as the rag rots away so will any infliction or illness, this in its way is a replacement for the original Celtic votive offering. Perhaps one of the best cloutie known trees is that at Madron Holy Well, which often has a profusion of coloured rags tied to it. Although today’s Samhain and other Celtic celebrations are recent creations, very different from ancient times, they do embrace the essences of those earlier ages. After all Christianity and Islam have changed and diverged widely from their original beliefs over the centuries, often through political influences.

The modern use of the term Celtic was coined in 1707 by Edward Lhuyd a Welsh linguist who had been contacted by Cornishman John Keigwin of Mousehole, who looked to ensure the preservation of the Cornish language. He linked the various Celtic languages splitting them into the Brythonic of Cornwall, Wales and Brittany, and Goidelic of Ireland, Isle of Man and Scotland. He concluded that the Brythonic branch had originated in Gaul reaching Britain as the Celtic culture spread across Europe. It is now believed that the Scottish Pictish tongue was also Brythonic, lost as the Goidelic variant later took over as it spread from Ireland.

To illustrate the widespread mystical, spiritual and other-worldly concerns here in Cornwall are a few of the places and activities sharing such interests. There is the very popular independently owned Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle begun by Cecil Williamson in 1960. This museum has a superb collection of artefacts, art and books covering all aspects of mysticism. The West Cornwall museum of magic and folklore begun in Falmouth in 2021 has now evolved into ‘Gwithti an Pystri - A cabinet of folklore and magic’. This is run by Steve Patterson who also produces podcasts which he describes on his website as ‘rambles through Folklore, Art, Magic and the landscape.’ There are some delightful podcasts by Sian Powell the wonderful and zany ‘Exhibition and Engagement Officer’ at Wheal Martyn Clay Works Museum with her Celtic Myths & Legends podcast channel. For those who love reading about Cornish folklore there are a multitude of books including those by Alex Langstone who also produces Lien Gwerin, a journal of Cornish Folklore.

When visiting a medieval Cornish church look out for the pagan Green Man. Quite a number of churches throughout Cornwall have carved bench ends or ceiling bosses with depictions of the Green Man. He has existed since ancient times and thought to have originated with Bacchus the Greek god of wine, the Roman Dionysus, alternatively the Greek god Pan associated with nature, wooded areas and pasturelands. The Green Man is associated with fertility and the cycle of the seasons and depictions of him can now be found everywhere besides medieval churches. The Celtic god Cernunnos the ‘Horned One’ was called many things throughout the wider Celtic world and worshipped as lord of wild things. He was also thought to be an influence for the Green Man.

When considering Celtic religion and beliefs one has to take in the wider Celtic world for information as Cornwall has nothing to add to that knowledge from ancient history, even historic Welsh and Irish text date from medieval times. The tribes who embraced the Celtic culture of the ancient pre-Roman world were found over most of Western Europe. Britain in pre-Roman times would have seen the whole island inhabited by the ancient Britons, these too were Celtic tribes speaking what is believed to have been the early forerunner of the Brythonic Celtic language. This evolved into what is today’s Welsh, Cornish and Breton languages. There were many individual tribes and many of these would have been divided into smaller groups living within a particular area

What we know of how our ancient forebearers practiced their Celtic religion during those times comes from ancient texts by non-Celtic peoples. This is coloured by the writers own agenda such as that by Julius Caesar and his wars in Gaul against the Celts that ended with the defeat of Vercingetorix in BCE 52. His writings entitled ‘Commentaries on the Gallic War’ helped define Celtic peoples as uncouth or unsophisticated which was as Romans saw the Celtic peoples, barbarians compared with themselves. This was especially true regarding those ancient Druids, which Caesar was especially keen to portray in a poor light by highlighting their activities relating to human sacrifice. There is little doubt that this was the case including use of wicker men where humans were burnt alive within a wicker human shaped framework. However, Caesar did acknowledge positive aspects including the study of astronomy and the cosmos, nature and the environment and also what we would term theology by the Druids. Besides Caesar other Roman writers of that age included the historian Tacitus who wrote about historical events in Britain and Plutarch who provided a description of Britain, naming its many Celtic tribes. We also know from archaeology over the past couple of hundred years that the Celts produced superb works of art and items of great beauty in gold and other metals.

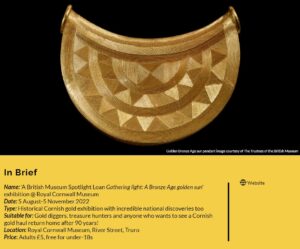

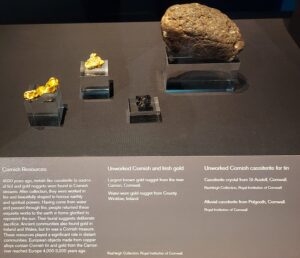

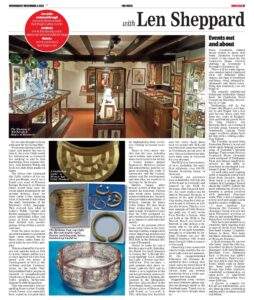

One of the greatest relicts from Celtic times is the Gundestrup Caldron, a large silver vessel depicting animals and gods, dated to the 1st century BCE held in the National Museum of Denmark. Nearer to home for just a few days more until 5th November the Royal Cornwall Museum is hosting the ‘A British Museum Spotlight Loan, Gathering Light: A Bronze Age Sun’ exhibition. This includes a gold pendant that dates between 1000–800 BCE and includes a rare depiction of the sun not previously seen on objects unearthed in Britain, discovered in the Shropshire Marches. Also on show is the Towednack Hoard, consisting of nine pieces of Bronze Age gold found in Cornwall in 1931, including four bracelets and two torcs. Each dates back to around 1400 BCE and were found at Amalveor Farm in Towednack parish near St Ives. This is the first time they have been seen in Cornwall for over 90 years. The RCM also has a number of torcs including the early 1st millennia, circa 100 CE, Pentire Neckring found in Newquay. Certainly not anywhere near as beautiful, but only one of two found in Cornwall, and donated to the RCM by Newquay Old Cornwall Society. An exact replica can be seen in Newquay Museum. A replica of the gold Rillaton Cup, dating from the Celtic period found at Rillaton in 1837 can also be seen. This is a very rare example of Celtic Bronze age gold, one of only seven from Northern Europe. Also not held at the RCM is the Morvah Hoard was found at Morvah in 1884 dating to between 1000 to 750 BCE and consist of six gold bracelets, thought to originated in Ireland. Perhaps one day the British Museum will return these Cornish Celtic treasures to Cornwall.

Observing these wonderful objects helps confirm the ancient Celts were not necessarily the unsophisticated tribesmen the Romans described in their writing. How much more we would know if Celts hadn’t relied on oral traditions alone and written knowledge from a Celtic perspective was available.

![[123] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 2nd November 2022 - Events Out and About Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 2nd November 2022 - Events Out and About](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/123-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-2nd-November-2022-Events-Out-and-About-291x300.jpg)