Ertach Kernow - Medieval education in Cornwall

Education in Cornwall is at the forefront of my mind having had the recent pleasure of giving an illustrated talk and taking part in question and answers sessions on Victorian Newquay to year six students at Newquay Junior Academy. That there is now a growing interest by schools in teaching local history is good for Cornish historic, cultural and environmental heritage. Although most questions related to Newquay and its history I was most encouraged by Cornish related questions, such as about Tre, Pol and Pen and the use of these in Cornish place names. For those of us who are keen to share and forward all aspects of Cornish heritage and mark Cornwall’s identity, encouraging young people to take an interest is key to the future.

Growth of teaching and use of Kernewek, the Cornish language, is growing apace in schools thanks to organisations like Goldentree Productions and their Go Cornish project. Also, the Cornwall Heritage Trust who help through grant funding transport and education in Cornwall’s historic heritage. Work by Cornwall Council in the proposed ‘Curriculum Kernewek’ seeking to broaden knowledge about Cornwall by extending the current, often isolated interest in schools Cornish studies is most welcome.

The purpose of the study document states; ‘Curriculum Kernewek helps pupils to understand and celebrate the distinctive quality of living and learning in Cornwall in the twenty-first century, to identify their own sense of being Cornish, to enable them to understand and to challenge the ‘anglicisation’ of Cornwall and the Cornish and to therefore feel a heightened sense of belonging to their local community and the Duchy. It also helps to foster in pupils an understanding of Cornwall’s history as an outward looking and international Cornwall, promoting global citizenship and a concern for sustainable development.’ That this proposal is being discussed is really an important step forward and hopefully will soon become embedded within Cornwall’s education system. However, the wheels of progress turn slowly and hopefully many schools will grasp the nettle instigating their own Cornish projects using local groups and organisations to provide support for such activities.

This is the present and hopefully the future; what of the past? Prior to the Henrician English Reformation the main source of education in Cornwall and throughout England came from ecclesiastical schools and colleges. Dissolution of the monasteries through the Act of Suppression in 1536 had given all religious houses with an annual income less than £200 to the Crown. The Second Suppression Act of 1539 dissolved all others giving their possessions to the king, but there still remained various ecclesiastical properties including endowments to various bodies such as colleges, hospitals and chantries. Chantries had been established by wealthy people with buildings or land paying priests to hold a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, and occasionally benefiting the local community through education. Acts of Parliament were passed in 1545 and 1547 and in Edward VI reign to deal with these. Chantry Commissioners were appointed who would investigate then transfer or uphold an endowment based on their findings.

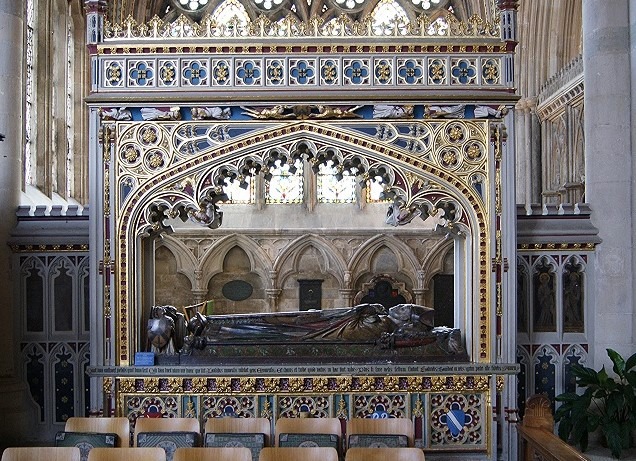

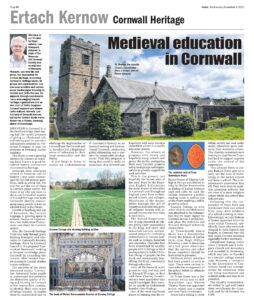

One of the most significant places of learning was the religious house of Glasney College at Penryn established in 1265 by Walter Branscombe as Bishop of Exeter between 1258 and 1280. In 1548 the college supported a public reading room as well as one of the vicars teaching a public grammar school. Glasney College as with other church establishments was dissolved in the Reformation but its major legacy for Cornwall are the Cornish miracle plays the Ordinalia and Bewnans Meriasek written by clerics there.

At Tywardreath where there was a Benedictine Priory the Bishop of Exeter (1505-1519) Hugh Oldham following a visit in December 1513 had given directions that the novices and other house members should be instructed in grammar. Evidence exists scholars had been present as early as 1450. There were various issues with the management of the priory before its ultimate dissolution.

In Truro there was a Dominican Friary and on 16th September 1397 Master Thomas Truro was appointed lector, which was a reader and most likely an educator. Friars had a calling to work within society and took wider social education more seriously than monastic orders. The chantry commissioners visiting in 1548 found Truro had land to support a priest under the control of the corporation. This allowed them to employ Richard Fosse aged 50 to carry out the work of ministering in the parish church and keep a school. The commissioners pensioned him off. They were keen to maintain grammar schools, but not ones of a more religious nature which this school they believed was. Following this the corporation of Truro built and maintained their own school from 1549, with evidence of a school existing in 1600. Interestingly certain Bishops of Exeter appointed friars for tasks within Cornwall, specifically those who were multilingual in both Cornish and English, as Cornwall was still very much Cornish speaking especially further westward.

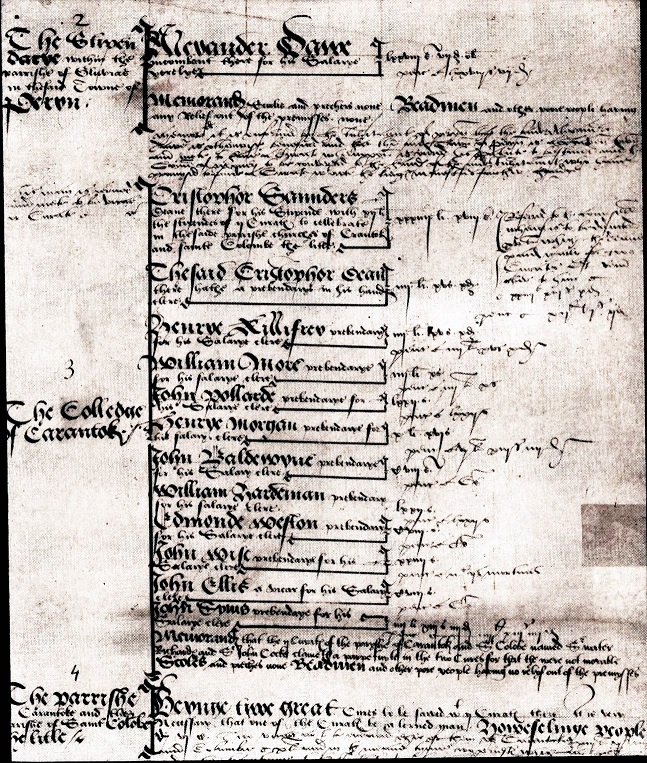

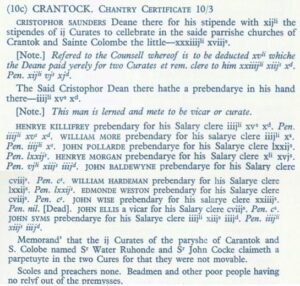

Established during Celtic times Crantock had a collegiate church and monastery and recorded in Domesday, which was later re-founded as a secular college around 1236. However, a visitation by the Archbishop of Canterbury found that arrangements for education were not being maintained and ordered clerks and boys to be provided. The chantry commissioners visited in 1548 and issued their certificates for Crantock, and for St Columb the Little. They said that there should be two curates and one of them should be a learned man, They stated there were no schools, but mentioned that there was a college founded within the parish of Crantock, questioning where the people were although salaries were paid. Land and tenements of the college were claimed.

Week St Mary is now a sparsely populated parish in north Cornwall, but in 1086 the manor of Week was recorded in the Domesday Book illustrating the historic nature of the settlement. Although not the earliest grammar school opened in Cornwall it was the first free school to be endowed. Thomasine Bonaventure a local girl made good, through three fortunate marriages, who on returning home from London in 1504 as a widow established and endowed a school in 1506. It ran for some 40 years and commissioners enquiring into public establishments said of it in 1546 ‘that ye sayde Chauntrye is a great comfort to all ye countries, for yt they yt lyst may sett their children to borde there and have them taught freely, for ye wch purpose there is an house and offices appointed by the foundation accordingly’. Sadly, some two years later it was closed through what was termed decay and transferred to Launceston.

At Saltash the chantry commissioners were informed in 1546 that a priest Andrew Furlong had been appointed schoolmaster by 1538 through an endowment. A John Smith had made the endowment producing £10 per annum for a priest to serve the local chapel of ease and to teach children freely in a school built within the town. The commissioners allowed the continuation of the endowment for teaching purposes.

Along with the priory at Launceston a grammar school had existed there before the 14th century. By 16th century proper endowments of land had been given to the mayor and town corporation by wealthy patrons to support a priest and teach children grammar. Teaching was a later addon to duties of a priest and the idea of endowed schools were not yet fully established. A Banham endowment of land supported two schoolmasters in 1548 one teaching reading and the other grammar. One might ask that given the Cornish language was still spoken in Cornwall what they were being taught. The chantry certificate for Stephen Gourge described him as ‘a man well learned, meet for the education of youth in the Latin tongue’. Later the school at Week was transferred to Launceston and education of children merged.

Bodmin was described in the chantry certificate of 1548 as the greatest market town in Cornwall. It seems that the priest there was a local man named as Nicholas Taprell aged 57 teaching grammar, the chantry commissioners ordered that he should continue. Following the chantry being taken by the crown Nicholas was to continue receiving his former salary of £5 6/- 8d directly from the government, which he did until at least 1555. He later became rector at St Mellion and was described as moderately learned. However, regarding the populace of Bodmin, the chantry commissioners commented ‘for the lorde knows the said twoo thousand people ar’ very Ignorant.’

There were a few other educational sites throughout Cornwall and during the reign of Edward VI some improvements made with the setting up of ‘free grammar schools’ for the poor. Most children did not attend as they needed to work to help support their households. Later religious groups, mostly non-conformists, would take on some of the tasks of education and this period will be shared in a later article covering from the later 17th century through to the 18th century in what became known as the Age of Enlightenment and to the first Education Act of 1870.

![Cornwall. BODMIN CHURCH. Hand coloured Steel Engraving. c1830 [29.03.2017] Engraving St Petrocs Church Bodmin circa 1830](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Cornwall.-BODMIN-CHURCH.-Hand-coloured-Steel-Engraving.-c1830-29.03.2017-300x205.jpg)

![[176] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 8th November 2023 - An Mis, Geology Awards, Rescorla Centre Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 8th November 2023 - An Mis, Geology Awards, Rescorla Centre](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/176-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-8th-November-2023-An-Mis-Geology-Awards-Rescorla-Centre.jpg)