Ertach Kernow - Limekilns a Cornish industrial legacy

Limekilns aren’t grand buildings like many churches, but without them these far more imposing medieval buildings would never have been constructed. Reduced local demand and improved transportation led to them to later being situated at quarry sites. Although no longer used these days at one time most communities especially those with coastal or river access, where vessels could navigate would have had them with limestone largely needing to be imported into Cornwall.

They do seem to pop up all over the place during my travels around Cornwall. These are not always particularly noticeable to most people, especially visitors, but are actually amongst the most prolific of industrial remains with some even being repurposed. Sadly, however in some communities where historic heritage is less valued they have been totally demolished or altered beyond recognition. Those that remain date primarily from the 18th and 19th centuries, some remaining in use well into the 20th century. As an important part of Cornwall’s industrial past where they survive they should be valued, and people made aware of their use within the local community.

Medieval Lime kiln, experimental archaeology by Digital Heritage on Sketchfab - Click to expand view and rotate using mouse or finger

The use of lime dates back to ancient times approaching 4,500 years ago. Later during the Bronze Age period in Minoan Crete, around 1800 BCE, it was used as lime mortar. The Romans used it widely to bond their building stones and also plaster as a covering for walls and ceilings and often seen in historic ruins. Closer to home it became used once the transformation of buildings from timber structures to stone construction began in earnest, certainly by the eighth and ninth centuries. By Norman times and the construction of large-scale churches, cathedrals and castles would have required lime mortar and likely that localised limekilns on that site would have been built and used.

As always click the images for larger view

Cornwall’s inland soil was rather more acidic than around the coast and was not particularly good agriculturally for the purpose of growing crops. As mentioned in an earlier article, sea sand often known as manure, was used to supplement the soil as well as seaweed. In the 18th and 19th century canals would be constructed, such as the Edyvean St Columb Canal for the purpose of moving sand to inland farming communities. The importance of use of sea sand was to help neutralise the acidity by raising the PH level. Sea sand containing greater amounts of shell debris was superior to sand containing mostly broken rock with the best Cornish sand for agricultural purposes found on the north Cornish coast at the Gannel and Camel estuaries, Trevose and Harlyn.

Records showing sea sand having been used in Cornwall for hundreds of years can be found in the Charter Rolls of Henry III. One entry states that; ‘Confirmation of the grant made by Richard, king of the Romans (Earl of Cornwall), for the common advantage of the land of Cornwall, allowing all the inhabitants to take sea sand without payment and to heap the sand on their lands, and to cart it throughout Cornwall for the fertility of their lands by a proper road assigned or to be assigned, provided that if the said king or those, through whose lands or on whose lands the sand is carried or heaped, be thereby damaged, they shall have reasonable compensation by the judgement of good and lawful men of Cornwall and of the steward for the time being, or by any agreement for a fixed sum which shall be made beforehand.’

From the 16th century lime by itself produced by lime burning in kilns from limestone was increasingly used. By the 18th century smaller primitive lime kilns were giving way to larger better constructed units better able to maintain a steady output for building and agricultural purposes. The rising population and need to increase agricultural output during the Napoleonic wars of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a major factor. It has been estimated that there were over 200 limekilns throughout Cornwall, so it is only possible to look at a few of these.

Lerryn is a village which although fairly inland has a river outlet to the sea via the River Lerryn and down through the River Fowey. Through its location Lerryn was well placed to have successful commercial lime burning business opportunities. This was clearly seen by Zephaniah Job the Polperro based merchant, perhaps better known for his interaction with the smuggling fraternity and known as the smuggler’s banker. Limekilns were a legitimate profitable business and one that Job could perhaps use to launder some of his less legal income. There had been lime interests at Lerryn before Job acquired and built his limekiln. With a wide river up to Lerryn Bridge and shipping quay’s, limestone could be imported, burnt and distributed inland better than from a more coastal harbour. Remains of two kilns still exist at Lerryn. Close to the historic quay is the two-pot limekiln originally owned by Job until his death in 1822, now with a residential property built over the top of it. The second kiln, a 19th century Grade II listed building is a far more identifiable kiln structure. It was built into the side of a steep slope which allowed it to be more easily filled from the top.

The ecclesiastical parish of Calstock bordering the River Tamar has nine recorded limekilns, more than any other parish in Cornwall. Not only was this an agriculturally productive area, but also benefited through River Tamar access with the opportunities to construct extensive sheltered quays along its banks. Being close to the fast-growing town of Plymouth and the Cornish town of Saltash closer to the mouth of the river there was a ready demand.

Within Calstock parish Cotehele Quay was very busy exporting farm produce during the 18th and 19th centuries and has two fine examples of limekilns. What appears to be the larger is actually only a two-pot burner and is perhaps one of the most well-known and photographed limekilns in Cornwall. It lies between what was the lime burner’s cottage and a granary store. The cottage renamed ‘The Edgcumbe’ is now a tearoom serving a variety of refreshments. Close by is an older three pot Limeburner which records show was certainly operating during the late 18th century and again is well preserved.

A short distance away is the Bohetherick limekiln at Cotehele Bridge constructed during the late 18th century or early 19th century. This limekiln was designed to operate continuously and having a row of three conical pots. As can be seen from the engraving dated 1817 it was close to the river so benefiting for importing limestone and for distribution of burnt lime for building and agricultural use. This limekiln has survived fairly well since its abandonment, untouched by the grasping hand of modern man.

The limekiln at Porthleven is obviously a valued and well-loved part of the villages historic past and included on their heritage trail. Having fallen into some disrepair it has been brought back from the brink by two local historians Martin Matthews and Stuart Pascoe in 2007. A Grade II listed building it was built in 1814 with a view to providing building lime and soil improvement. With the demand for lime diminishing the last recorded delivery of limestone by ship was recorded in 1910, although small amounts were transported in by road for occasional use. During the Porthleven Food Festival a bespoke awning surrounds the circular kiln when it serves as a bar, as was the case during our visit in 2023.

Porth Navas typical of small Cornish communities with river access had a limekiln which operated on its busy quay as the village exported quarried stone during the 18th and 19th centuries. Located off the Helford River access for shipping was crucial to the development of the village. The limekiln was built by the Mayn family, local landowners and merchants, and was an important part of Porth Navis as it was then known during its 19th century industrial golden age. Now developed into a holiday home something of the old kiln still exists but sadly not even mentioned in the National Heritage Protection Plan and unlisted.

Readymoney Cove near Fowey has a rather strange ornate Grade II listed limekiln. Built by Wiliam Rashleigh of Menabilly in 1819 he would have used it for his own estate construction including his house at Point Neptune. His son, another William is thought to have added the ornamental turrets at some point before 1900. Purchased in 1929 by Jesse Julian it was restored, and a viewing area added. Some further transformations took place to celebrate the jubilee of King George V in 1935 and later restructuring as toilets and a café, with benches and modern lighting added in 2017.

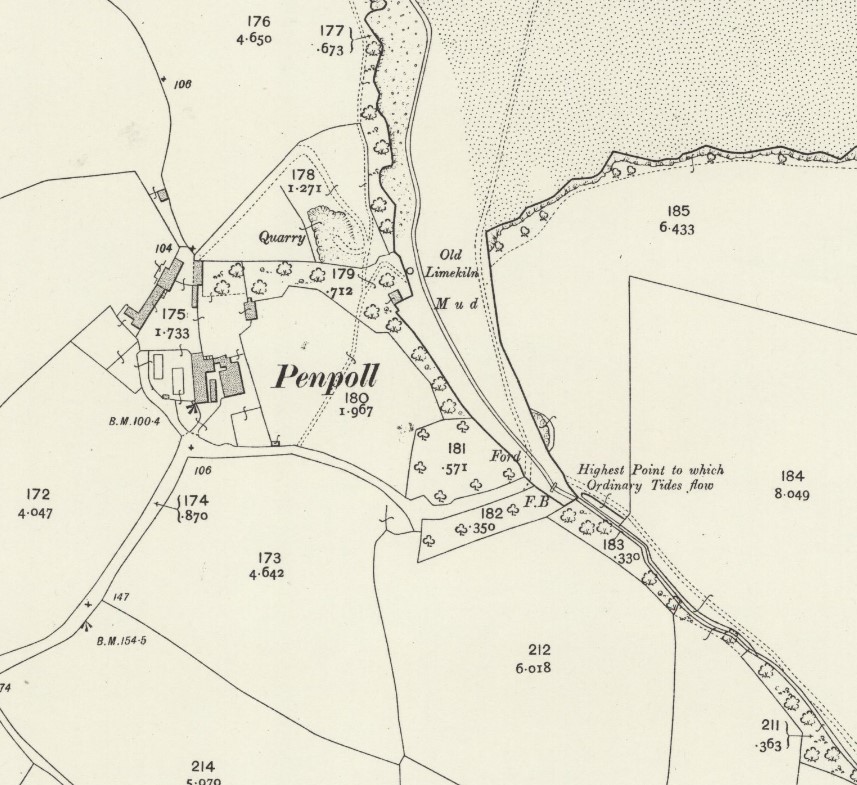

At Newquay there was a limekiln on the River Gannel at Penpoll Creek that would have received imported stone via the quay also used to export iron ore and other minerals including quarried stone. Little now remains, but this area is an interesting compact 19th century industrialised area with the limekiln noted on early 20th century maps. Further limekilns found at Newquay were included in the estate of Richard Lomax owner of the Manor of Town Blystra in 1836, and one at Towan Head which was thought to have been constructed by J T Treffry following his purchase of the manor after 1838.

Hopefully this short overview with some examples will encourage readers to look out for limekilns as they travel through Cornwall. Ertach Kernow would welcome images of these kilns which would be attributed to the photographer and added to this article’s webpage.

![[193] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 6th March 2024 - Visiting European students, workspace museum collaboration Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 6th March 2024 - Visiting European students, workspace museum collaboration](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/193-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-6th-March-2024-.Visiting-European-students-workspace-museum-collaboration-282x300.jpg)