Ertach Kernow - Cornish folktales and stories saved

Cornish folktales tell stories about Men an Tol and the curing properties of passing through the ringed stone

Cornwall often referred to as the land of myth and legend has much to thank Robert Hunt for ensuring that these folk stories have survived through to the present day. Even now booklets can be bought in bookshops throughout Cornwall published by Cornwall based publisher Tormark Press covering aspects of Cornish folklore compiled by Hunt in the 1860’s. The booklet Cornish Legends contains a selection of stories collected by Robert Hunt and was the first book in my Cornish library when bought for me by my Dad over fifty years ago.

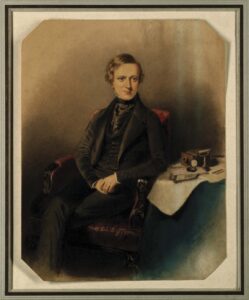

Robert Hunt was born in Plymouth Dock, which would be renamed Devonport in 1824, later merging with Plymouth and East Stonehouse becoming the City of Plymouth in 1928. His parents Robert Hunt and Honour Thomas were married in the parish of Stoke Damerel on 25th June 1805. He wasn’t home for long and rejoined his ship HMS Moucheron, where he was a carpenter, heading for the Mediterranean but must have returned home again briefly in late 1806. HMS Moucheron vanished in early 1807 with all her crew of ninety men and was declared paid off effective of 7th June 1807. Robert and Honour’s son Robert was born on 6th September 1807 and brought up in Plymouth Dock where he lived with his mother until aged seven. With relatives in Penzance, where she seems to have originated from, Honour and young Robert moved there where he attended school. Later he was to move to London to study for a medical profession, which didn’t work out well for Robert. He then became apprentice to a pharmacist practicing in London and over time met a good number of people who would through their kindness enhance his knowledge and interests. The death of his grandfather leaving him a property in Fowey gave him funds to explore Cornwall collecting stories. Returning to London he devoted his time to his employment in a chemical manufacturers and towards science, but illness would again see him returning to Cornwall. Throughout his life he would travel backwards and forwards between London and Cornwall involving himself with and also setting up Cornish organisations mainly relating to mining and minerals.

Following his death, a mineralogical museum at Redruth Mining School had been established in his memory by the Miners Association of Devon and Cornwall he helped found. Called the Robert Hunt Memorial Museum, this closed in 1950 and the collection transferred to the School of Metalliferous Mining, now the Camborne School of Mines. Here they have a large mineral collection, some of which can be viewed physically but also seen online in their virtual museum. One can hope that some reference of appreciation remains to the work of Robert Hunt towards this collection.

His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography shares the huge amount of work he undertook, and the publications written. Much of this related to mining and minerals on a national level outside Cornwall, but he also became secretary for the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic in 1840 and later in 1859 vice-president. Hunt also took a great interest in early photography and would become a significant person in the founding of photography and photographic processes. Published in 1841 Hunt was the author of the first English-language manual and history of photography, ‘A Popular Treatise on the Art of Photography’. Professor James R Ryan wrote in a recent paper; ‘Drawing in particular on recent studies on networks and the geography of science, this article examines the significant but frequently overlooked contributions made to early photography by the chemist and popular science writer Robert Hunt (1807–87) as a way to open up questions about the spatial networks of early photography….. This article argues that Hunt’s foundational contributions to early photography which were widely recognised in the half century after his death need to be better appreciated and understood within the setting of spatial networks of science and applied arts at various scales.’

Although his interests were multifaceted and his many achievements mainly within the scientific and mining community it is his work relating to collection and preservation of Cornish folklore and myths that are the main focus here. Robert Hunt with his work in recording stories, myths and folktales was at the forefront of the later revival period by reminding people of Cornwall’s folk history and traditions sharing this to a wider audience.

After centuries of cultural suppression since the Tudor period this was a time when Cornwall was just beginning its re-emerging with its own separate identity of nationhood rather than that of being part of England. A number of scholars and writers had helped keep the Cornish language alive through recording usage and creation of dictionaries into the 19th century. Awareness by people such as William Scawin and a likeminded group in the late 17th century had seen the danger to the Cornish language and wider culture, beginning the work of early preservation. Better known are people such as Henry Jenner and Robert Morton Nance who would continue this work into the early 20th century and establish Cornish heritage organisations through the Old Cornwall movement and Gorsedh Kernow.

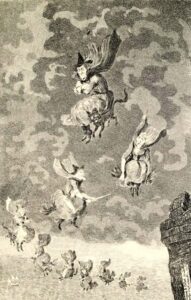

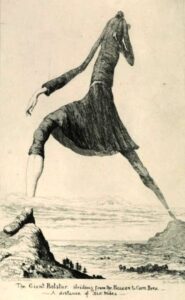

Hunt’s first edition of ‘Popular Romances of the West of England’ with the more important subtitle of ‘Or The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall’ was published in 1865. A droll in Cornish dialect is an oral story that was shared by itinerate droll tellers throughout Cornwall and who were by Robert Hunt’s time becoming scarce. These droll tellers it was said also used a mixture of spoken word and song often accompanied by a musical instrument.

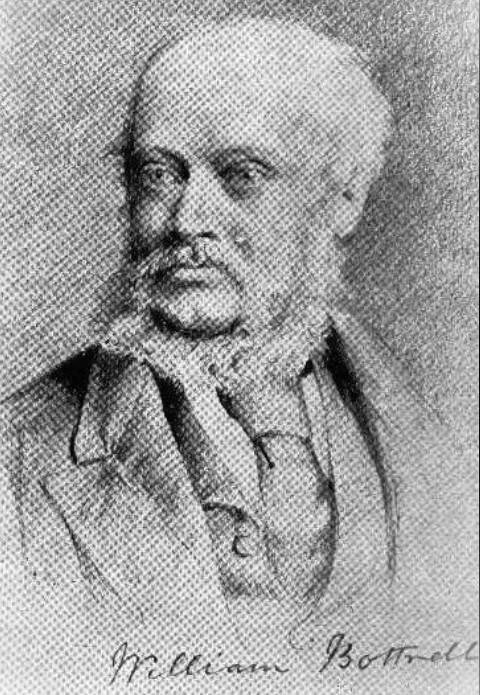

At a similar time to Hunt, William Bottrell was also working on collecting Cornish stories and his ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’ was first published in 1870 and a further volume in 1873. A final volume ‘Stories and Folk-Lore of West Cornwall’ was shorter as Bottrell was taken ill with a stroke and unable to complete this edition. Bottrell had contributed stories to Hunt’s ‘Popular Romances of the West of England’ and was acknowledged in the introduction. Stories were also contributed by Thomas Quiller-Couch, father of the famous Fowey novelist Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, and was mentioned in the text so readers are aware of his exact contributions. Bottrell’s stories tend to be longer and perhaps more in keeping with the original oral stories where the droll teller would have adapted and wound up his audience elaborating on the basic story. So even though Bottrell may have obtained first hand, most or even all of his stories, Hunt’s importance was that he ensured their wider distribution from a greater area throughout Cornwall. Perhaps today with peoples shorter attention span and danger of information overload Hunt’s condensed stories are more readable, creating opportunities for today’s storytellers to elaborate and entertain in their own ways on those original folktales. A great number of other writers have published localised stories, often in Cornish dialect and also included within books covering a particular subject. Those interested can find a list of books I’ve collected on Cornish myths, legends, folklore and traditions in due course on the website blog for this article.

The third edition of ‘the Drolls, Traditions and Superstitions of Old Cornwall’ was published in 1881, just a few years before Hunt’s death. In the preface to this edition, he wrote ‘The growing inquiries of those who are desirous of knowing something of the ancient Cornish miners, of the old peasantry of this peninsula, and of the aged fishermen who almost lived upon the Atlantic waters, have convinced me that a third edition of this volume of folklore has become a necessity.’ Although this work in its full entirely is less well-known the smaller modern booklets with targeted subjects are widely bought and distributed. These include many of the stories that have become a staple for Cornish people and visitors interested in Cornish heritage. Hunts original publication included stories of saints, holy wells, sorcery and witchcraft, miners, fishermen and sailors, superstitions and traditions with probably some of the most famous included in Hunt’s stories relating to King Arthur. Perhaps one famous story that wasn’t included in Hunt’s works was the Mermaid of Zennor, thankfully told in Bottrell’s ‘Traditions and Hearthside Tales of West Cornwall’. This has been retold many times and a recent adaptation of this tale was recorded by Cornish dialect expert Paul Phillips in his ‘The Alternative Mermaid of Zennor Story’ This can be found on the Kowethas Ertach Kernow YouTube channel by clicking the button for www.youtube.com/@ErtachKernow along with some other stories and folktales

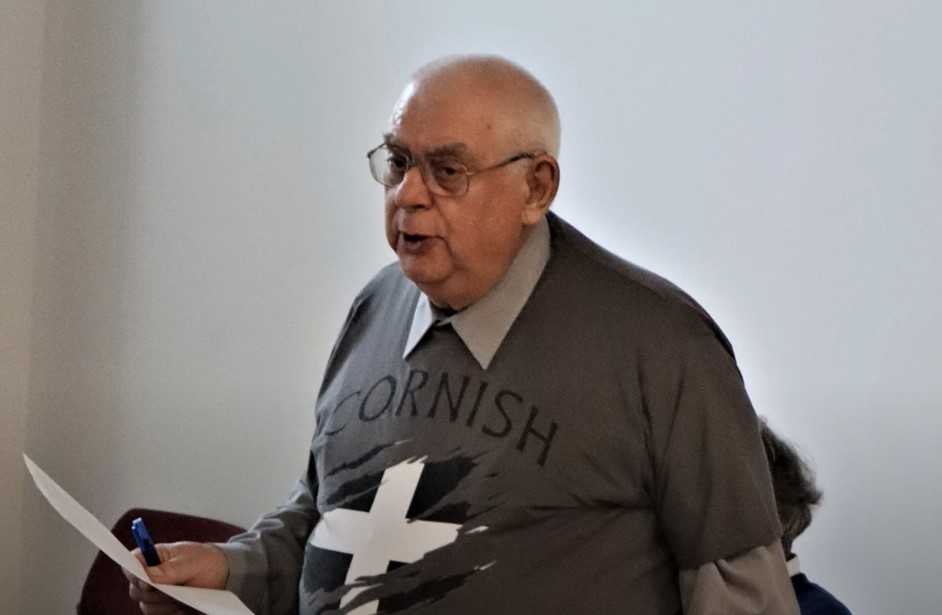

The following verse was printed by William Bottrell in his ‘Traditions and Hearthside Tales of West Cornwall’ in 1870. ‘The Cornish drolls are dead, each one; The fairies from their haunts have gone: There’s scarce a witch in all the land, The world has grown so learn’d and grand.’ Written by Henry Quick (1792-1857) known as the Zennor Poet it seems to portray the end of Cornish drolls. Fortunately, with people such as William Bottrell and Robert Hunt having recorded these oral stories in the 19th century and shared them in books they haven’t been lost. The droll tellers in the old sense of the word may have gone, but there are still people telling stories. The Liskeard Storytelling Café has a programme of meetings, and it was good to share some stories from people such as Mike O’Connor, Moe Keast, Barbara Grigg and Yvonne White on the Association for Cornish Heritage YouTube Channel for the online Newquay St Piran’s Festival in 2021. With the coming of the technical age Cornish droll telling has evolved to meet the 21st century.

![[172] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 11th October 2023 - Sad news for Cornish museums and Cornish Wrestling Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 11th October 2023 - Sad news for Cornish museums and Cornish Wrestling](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/172-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-11th-October-2023-Sad-news-for-Cornish-museums-and-Cornish-Wrestling-1.jpg)