Ertach Kernow - Cornish fishing the early years

Fishing along with tin production is one of Cornwall’s most historic occupations and industry, reaching far back to before what might be termed time immemorial. Small coastal settlements have been found dating from the Bronze and Iron Ages close to estuaries and coastal areas best to benefit from shellfish and fish coming close to shore. Evidence of this can be found where these early settlements have been uncovered and their middens, or waste piles found with a variety of shells and bones. Archaeologists love middens as they tell so much about our Cornish ancestors and how they lived. Those sites that have survived have often been protected by the shifting sands that eventually covered them, probably forcing the inhabitants to leave. An example which many people will be aware of from later medieval times are the shifting sands at Penhale which eventually covered St Piran’s Oratory and later the 12th century medieval church built to replace worship at the oratory.

An archaeological site at Gwithian has proved very important, but for our purposes besides the many aspects of the site relating to farming and other life evidence, are the remains of maritime food resources. The well-known Cornwall based archaeologist Jacky Nowakowski in her 2009 paper wrote; ‘These include cattle, sheep/goat, pig, roe and red deer and dog. Oysters, a whale bone and many marine molluscs (mussel, limpet and whelk) show that, in addition to arable and stock farming, fishing and harvesting the nearby rocky shorelines, was an increasingly important seasonal part of daily life.’ This was however subsistence use of maritime resources and far from the later early and mid-medieval growth of fishing into an important part of Cornwall’s economy.

Cornwall’s connections to England were primarily via the sea lanes due to the difficulties in travelling overland and especially transportation of goods. This would have encouraged a number of coastal communities that had sheltered coves and estuaries, later harbours, to engage with the sea including fishing. The coming of the Normans who despite being ferocious warriors were what might be termed pious Christians, with the church encouraging the faithful not to eat meat on about 130 days of the year. As fish did not count as meat this resulted in greater demand for this alternative. Rising demand for especially saltwater fish led to specialised fishmongers becoming established amongst new fairs, markets and market towns being created. Most of the markets and fairs established in Cornwall by 1516 were created during or before the 14th century.

Although Cornwall is now mostly associated with coastal fishing there would have been a time before mining became industrialised when Cornish rivers and estuaries would have provided fish for communities. Water pumped from the mines carrying sediment gradually silted up many rivers and the higher regions of the estuaries and they no longer teemed with fish to be caught in weirs and nets strung out into and across rivers. At the mouth of estuaries and tidal reaches members of some communities would have built a fish trap or weir to catch fish either on the incoming or outgoing tide. An example of this has recently been found at River Teifi at Poppit in Wales and thought to be about 1000 years old, built to catch migratory fish. Once the fish were herded into the trap they would have been scooped out with baskets or nets. Although none of these have been found in Cornwall there is no reason to think that traps and weirs wouldn’t have been built in Cornish rivers and estuaries. Larger Cornish rivers still attract anglers for leisure, including at our modern reservoirs, however the days of being able to feed a community on an ongoing basis from rivers with medieval type traps is long gone. Estuaries, especially on the south coast would also have been a place that oysters would have been harvested since prehistoric times and has continued as small, industrialised businesses through to the current day. With its long coastline mussels would have been a plentiful food source women and children would have been able to collect. Even today a good number of local folks still do.

Although hide covered framed coracles would have suited prehistoric people, early medieval boats had developed into plank-built vessels held together with cord or rope. These larger boats allowed for greater coastal fishing opportunities gradually evolving into an industry. Fish caught included cod, hake, flounder, plaice, sole, whiting, herring and of course pilchards. The methods used varied depending on species. With Cornwall having been at the centre of trading for centuries, through tin production and export, a new merchant class with overseas networks had grown up. First mention of Cornwall having a serious fishing industry and exporting was during the reign of King John (1199-1216). In 1254/55 the then famous poet Michael of Cornwall defended his homeland against a scurrilous poetical attack by Henry of Avranches, a well-known court poet of that period. Henry had named Cornishmen as the fag-end of the world. Michael replied ‘Twere needless to recount their wondrous store, Vast wealth and fair provisions for the poor; In Fish, and Tinn, they know no rival shore.’ Fishing was it seems creating wealth and employment.

This period of fishing on a more industrialised scale in Cornwall during the 12th century saw fish exported primarily to Spain, Brittany and territories in France connected to the English crown. King John had enabled increased trade by allowing French fishermen to use Cornwall and England’s coastal waters and this encouraged the export of salt from France for curing. This in turn allowed the resulting cured fish to be exported to Europe which continued for many centuries. During this period, it was St Ives and Mousehole which dominated Cornish industrial fishing followed by Fowey, Newlyn and Marazion. By the late 15th century there were fishing communities around the whole Cornish coast and on his journey to St Michael’s Mount the antiquarian William of Worcester commented in 1478 that there were 147 havens around the Cornish coastline between the Tamar and Penzance. There were obviously many more on the north coast of Cornwall including early Newquay. That there were thriving fishing communities at both Newlyn and at the haven in Tewynplustri, now Newquay, is illustrated through indulgences given to help rebuild the piers there in 1437 and 1439 by Edmund Lacy, Bishop of Exeter.

Mousehole was a place well-known to Richard Earl of Cornwall as in 1242 he landed there after his ship nearly foundered in a storm. This was the first mention of Mousehole, being referred to as ‘pertusum muris’ or in English ‘the hole of the mouse’. Records show that during the early 14th century there were 16 fishing boats and Mousehole was compelled to supply the Duke of Cornwall’s household at Restormel Castle with fresh fish. Besides fishermen there were many merchants exporting fish from Mousehole. Evidence of early medieval settlements around St Ives Bay include remains of a nearby buried chapel at Gwithian. Some excavation was carried out in 1827 following its burial by sand and in his Cornish Churches of West Cornwall J T Blight gave a good description of this historic building. Originally built as a timber oratory and later rebuilt in stone between the 8th to 9th centuries. St Gothian's Chapel and its surrounding graveyard served as the church and cemetery for Connerton, the original name for Gwithian, until the 13th century when it finally succumbing to the shifting sands. No doubt many other small coastal fishing communities were lost and buried, including famously along Penhale Sands between Crantock and Perranporth. This left St Ives to later become the dominant fishing port on the North Cornish coast along with Padstow on the River Camel estuary.

The seaport for the St Ives Bay area was originally Lelant on the west bank of the Hayle estuary a much larger settlement than Porthia, as St Ives was then known and still is in the Cornish language. The population of Porthia grew so that by 1377 the number of people was about equal and Lelant had ceased to be a port. Early days for fishermen and fish merchants in Porthia were difficult with remaining vested interests in Lelant and the large markets at Mousehole, and Marazion. The most important factor leading to the growth of St Ives came with the granting of borough status following Robert Willoughby, later Baron Willoughby de Broke, becoming owner in 1487. He built the first stone pier there primarily for the protection of the villages fishing vessels. Following incorporation as a borough the corporation took many means of protecting its own merchants and fishing interests, leading to its later importance as a fishing town.

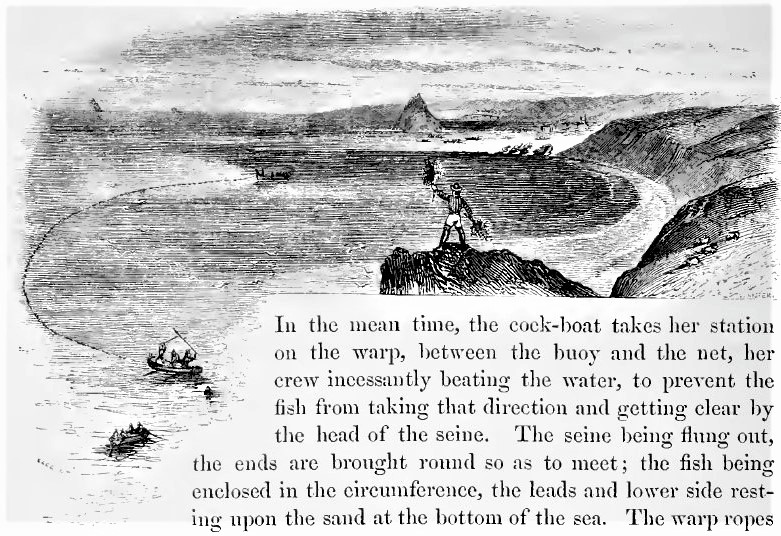

Many other small villages would grow into important fishing towns over the following centuries. During the Tudor dynasty from 1485 many laws were laid down to help maximise the benefits of income and taxation Cornwall had to offer the crown. Certain towns in particular benefited through parliamentary acts and representation well as town and borough byelaws relating to fishing as well as tin. It was during this period that seine net fishing began to take hold of the fishing industry over that of the driftnet fishermen. Gradually from that period the pilchard became to dominate Cornwall’s fishing industry creating great wealth for those rich enough to invest in the necessary nets and boats. The will of Thomas Trethurffe shows that in 1528 he leaves to the church of St Columb Minor and Alice Christopher his boat and seine net and all related things held at Towan. This was the main settlement that on joining with the hamlet around the nearby medieval pier became Newquay.

The period from the Tudor age through to the huge catches of pilchards during the 19th century will need to be continued in a later article along with a closer look at some important fishing ports.

![[170] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 27th September 2023 - Importance of twinning & internal tourism Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 27th September 2023 - Importance of twinning & internal tourism](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/170-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-27th-September-2023-Importance-of-twinning-internal-tourism-283x300.jpg)