Ertach Kernow - Cornish coastal defences

Cornish historic coastal defences under spotlight

Cornish coastal defences up to the beginning of the 20th century shows only two major structures which are really well-known. Digging deeper the mid-19th century saw substantial construction around what is often known as Cornwall’s forgotten corner on the Rame peninsula. With the coming of aircraft and other more advanced maritime vessels the type of defences deployed would change immeasurably. Gone were the castles and blockhouses located at prime invasion spots in estuaries and in came the dragon’s teeth along beaches to prevent tanks and landing ships, often supported by pillboxes and concrete gun emplacements. Many of these still exist or are exposed on beaches after a storm, but it is the historic defences we are considering here.

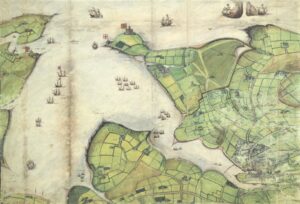

Cornwall was somewhat isolated and far from the strongholds scattered around England and its coastal defences. The north Cornish coast with its cliffs and dangerous rocks along with winds if unfavourable would cause certain destruction to an invading force. The only points of real opportunity being at St Ives with very limited capability for invasion and the Camel Estuary with its natural defences of shifting sands at the Doombar. Of course, any Spanish or French invasion force attempting Cornwall’s north coast would have to successfully navigate treacherous waters around Land’s End and rely on fair weather and favourable winds before considering any landing. Tintagel is not included as it was not in reality a castle aimed at coastal defence.

The south coast of Cornwall was a different matter, Carrick Roads with its deep-water harbour and rivers running inland would make a fine place for an invasion force to capture and land. The River Fowey was also a tempting target albeit secondary to the estuary of the River Fal. Hazardous rocks around the Lizard peninsula and south westerly storms rule Mounts Bay out of contention along with the presence of St Michael’s Mount as a serious defensive position. There were smaller attacks from time to time on unprotected communities, but nothing that could be termed an invasion.

As always click the images for larger view

Pendennis Castle is one of a pair constructed during the reign of Henry VIII the other being St Mawes at the entrance to Carrick Roads. Of the two it is Pendennis that is the larger more famous with greater visitor numbers. These two castles were late constructions when compared to the earlier medieval round castles at Launceston, Trematon and Restormel and built for very different reasons. Whilst the earlier ones were about protection for the inhabitants and troops relating to internal conflict the latter ones were about protection from attack from the sea by France and Spain. They would continue to be a bastion against foreign invasion of Cornwall and England through the reign of Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I and into the 19th century.

St Catherines Castle at Fowey was an earlier fortification built in 1536 to protect the Fowey River augmenting the earlier blockhouses which controlled a chain across the river to prevent access. This small fortification was a forerunner to the larger Henrician castles at Pendennis and St Mawes and in comparison, somewhat primitive. It was maintained in good repair through to the civil war but by 1685 described as ruinous. There were refurbishments and rearmaments during the mid-19th century as part of the upgrading of coastal defences. Abandoned once more it was again rearmed in 1940 and used for anti-aircraft, a mine control firing point and had a pillbox built beside it. Now it is a place of historic interest to visit.

The other major coastal estuary access was the River Tamar on the border between Cornwall and England. This stretched far inland and would have created great opportunities for an invading army had they forced any defences. Amongst the earliest defences of the river area on the Cornish side was Trematon Castle completed in the 12th century. This was long before any serious artillery beyond the ballista a large-mounted crossbow and the mangonel a single-arm torsion catapult and later the mangonels much larger cousin the counterweight trebuchet capable of throwing huge rocks at castle defences. Strategically placed it overlooked the confluence of the Lyner and Tamar rivers.

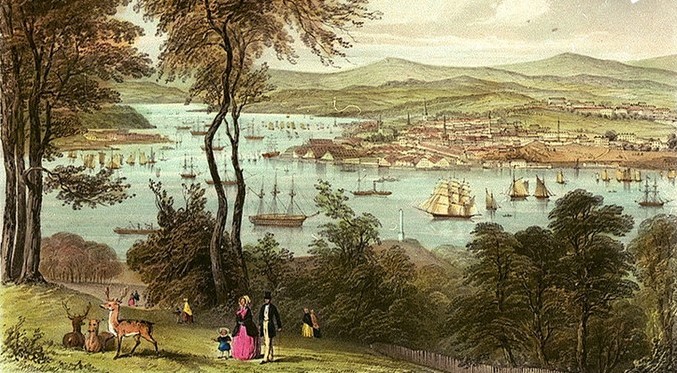

There were over the following centuries various defences built at the mouth of the Tamar and Plymouth Sound aimed at protecting the naval dockyard at Devonport, the fleet anchorage in the Hamoaze off Torpoint and the area around Plymouth. They also protected many Cornish towns and communities on the western side of the Tamar, the closest being Saltash, so could be considered part of Cornwall’s coastal defences.

As part of the Henrician coastal defence programme of the 16th century was the blockhouse constructed by the Edgcumbe family in 1539. This lies adjacent to the Royal William Yard at Plymouth at Devil’s Point. As Devonport at what would become Plymouth grew into a major naval base there came increased interest in protection of fleet anchorages and dockyard facilities. These defences extended substantially into protecting the area of Cornwall’s Rame peninsula. The blockhouse built by the Edgcumbe family during the period of Henry VIII was no longer anywhere near sufficient and the defences here were improved with the addition of artillery batteries at what is known as the ‘Western King's Redoubt’. On the Devon side of the Tamar. Two small forts or redoubts were constructed in 1779 and later in 1859 the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom had recommended a further upgrade with a larger redoubt. This remained armed until 1956 saw the abolition of coastal artillery. At the same time the ‘Western King's Redoubt’ was constructed further forts were constructed around Plymouth in Devon as well as in Cornwall. These 19th century defences from the 1859 Royal Commission were often called ‘Palmerston Forts’ or follies named after Lord Palmerston the Prime-Minister who was a strong advocate for their construction.

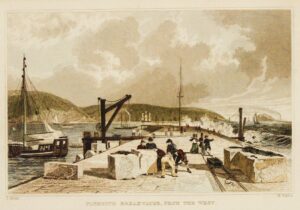

During the Napoleonic wars to support smaller batteries on either side of the Tamar entrance at Cawsand and Devil’s Point it was decided to construct a breakwater across the entrance to Plymouth Sound. This had been considered earlier and the plans may have been based on those drawn by George Matcham brother-in-law to Lord Nelson. Begun in 1812 and four million tons of rock later it was completed in 1814, at 1,710 yards just short of a mile long. The 1859 Royal Commission also led to the construction of the Breakwater Fort, thirty-five yards inside the breakwater and structurally completed in 1865. It was not fully armed until 1880 with 24 guns of various sizes with the larger main armament of 12.5” and 10” guns protected by steel casements over two feet thick. By the 1890’s these had been replaced by four 6" quick firing guns. Following use in various military guises during subsequent conflicts it was finally abandoned as a military structure in 1976 and is a registered scheduled monument.

On the Cornwall side of the border there were other Palmerston Forts. This was the largest construction of coastal defences since the days of Henry VIII although for Cornwall this was primarily around the mouth of the Tamar and stretching into the Rame peninsula.

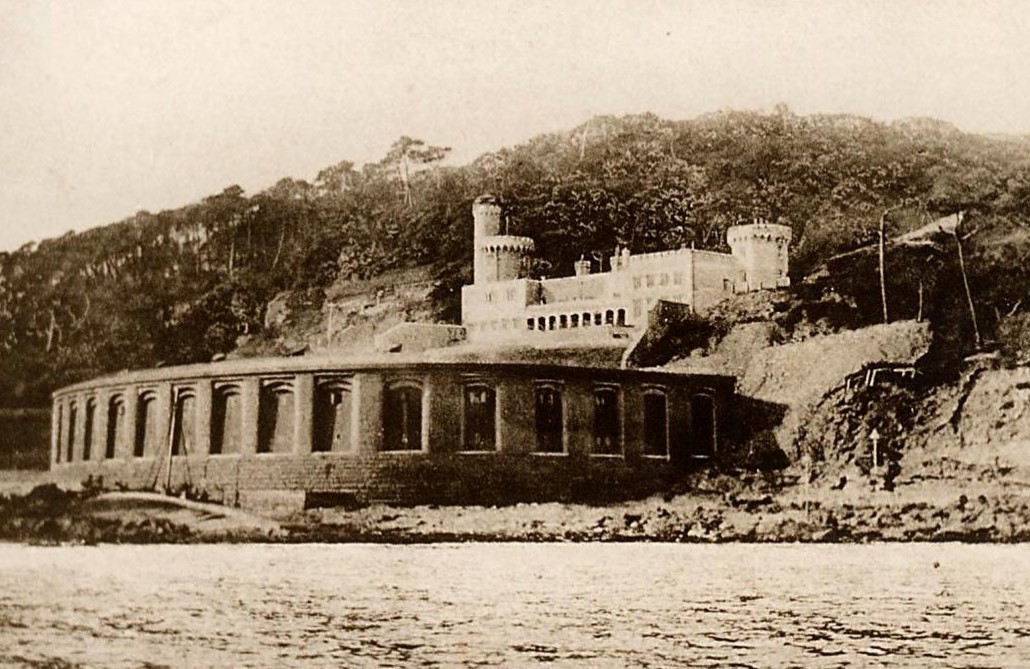

Just within the area covered by the Plymouth Sound breakwater is Fort Picklecombe covering the western entrance. An earthen bank fort had existed since the Napoleonic conflicts but saw rebuilding in substantial form between 1864 and 1871. The two-storey semi-circular building faced with granite blocks and iron shields supported forty-two 10” and 9” guns, creating a substantial defensive fort. Like the Breakwater Fort it was rearmed with 6” quick firing guns in the 1890’s and again rearmed for 20th century wars.

Also covering the western side of the entrance to Plymouth Sound were the gun batteries at Cawsand with the first defensive construction completed there in 1779 consisting of two redoubts. The Royal Commission saw these defences strengthened considerably with the building of substantial fortifications between 1860 and 1863, which was subsequently added to over the following decade. Aiming to prevent a landing and add support to Picklecombe Fort the battery was 130 feet above the highwater mark with angles of trajectory from horizontal to 45 degrees downward to cover the foreshore. Earlier defences following an incursion by a small number of Spanish troops led to plans for a small blockhouse, this was never completed. It was abandoned by the military in 1926 falling into decay, but like Fort Picklecombe was developed into residential properties. It is a scheduled monument and Grade II listed.

Whitsand Bay also had a number of fortifications constructed as part of the Palmerston series of coastal defences and also during the late 19th century. There was the Polhawn Battery built in 1864 to guard the western approaches to Plymouth and prevent a landing at Whitsand Bay. Polhawn’s guns were removed in 1898 and during World War I it was used as accommodation for gunnery officers from the Whitsand Bay Battery. The Tregonhawke battery southwest of Millbrook was constructed between 1890 and 1893 but did not survive as an active gun battery into the First World War.

Further west Tregantle Fort close to the village of Antony was constructed between about 1860 and 1865. It had provision for thirty-five large guns with accommodation for 2,000 troops. Along with the fort the area has been in use by the military as a base to current times for training and ship monitoring purposes. There were other smaller gun placements and defences within the area now removed. Scraesdon Fort also close to Antony is situated on the northern side of the peninsula leading to Rame Head, overlooking the estuary of St Germans or Lynher River. Although structurally completed by 1860 and designed to accommodate 27 guns. These were never mounted after a 1868 report suggested arming was should only happen in case of need.

Those interested in some of our industrial age fortifications may find those labelled ‘Palmerston Forts’ worth investigating. Perhaps we should be thankful to Lord Palmerston for adding to Cornwall’s heritage along with its earlier hillforts, medieval and 16th century castles.

![[195] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 20th March 2024 - Ertach Kernow - A labour of love shared Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 20th March 2024 - Ertach Kernow - A labour of love shared](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/195-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-20th-March-2024-Ertach-Kernow-A-labour-of-love-shared-282x300.jpg)