Ertach Kernow - Antique books share stories

This week whilst meandering through some antique books looking for some interesting, strange or even wild inaccuracies I came across my copies of The Western Antiquary. Dating from March 1881 they contain all sorts of pieces of information submitted by members of the public relating to families, historic facts, cultural activities or just some obscure piece of knowledge that someone over 140 years ago thought they might share with readers. Also, perhaps the opportunity to ask questions of a far wider audience than the local community, was this the Googling of those times? Beware though, there was much waffle and inaccuracies, similar to many comments on Facebook today.

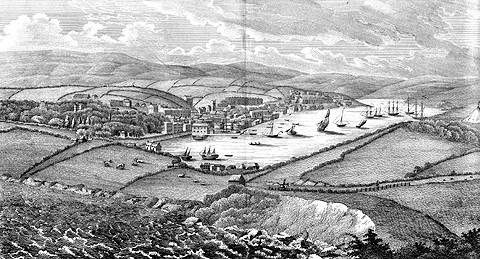

The origins of Falmouth as a place name seem to have preceded the official charter naming the town granted by Charles II in 1661. Falmouth was used in relation to the bay or area rather than the settlement, a small hamlet by the name of Smythwicke or some variant spelling. The charter states; ‘that Village from henceforth shall not be called, named, or known by the name of the Village of Smythwicke, but in all times hereafter shall be called, named, or known by the name of our Town of Falmouth’. Now it seems Smythwicke was also known as Penny-come-quick by which a popular local pub is now known. Here is the tale as told in the Western Antiquary in 1882.

‘Prior to the year 1600, a certain person, a female servant of Mr. Pendarvis, of Pendarvis, about 10 or 12 miles from Falmouth, erecting a house, came hither and dwelt in it.’ This seems evidently to have been a house of entertainment, as her master, Pendarvis, in order to encourage her in business, directed her to brew some ale against a certain day, when he would come and bring a company of gentlemen with him, and help her to a little money by drinking it out. This order she most readily obeyed. But the biddance and the promise plainly show that it must have been prior to the year 1552, as early in that year a law was made, for the first time, requiring alt houses and tippling houses to be licensed. But on the present occasion not a word is spoken about any license for this solitary house. It happened about this time, while the ale was put in readiness for Mr. Pendarvis, that a Dutch vessel entered the harbour, when the crew, coming on shore, laid siege to the barrel, and actually drank all the ale. This is the earliest intimation that occurs of any Dutchmen visiting this harbour. But they seem afterward to have had a large connection with it, and to have left memorials of their frequent visits in the name of Flushing on the one side, and in that of Amsterdam, given to some houses, on the other. Ignorant of what had passed, Mr Pendarvis and his company came at the time appointed and called for the ale; when they were informed by the servant that she had none left. Her master expostulating with her on the impropriety of her conduct, she replied, ‘Truly, sir, the Penny come so quick, I could not deny them.’ The country people around caught the story, and, from that time, gave to Falmouth the name of Penny-come-quick. The house which was the scene of the transaction has been marked as the earliest in the town. A smith's shop was erected on the margin of the creek, at a very early period ; from which circumstance the village which in process of time gathered around it was denominated, Smithike.

A concise warning for those living in Liskeard could be found in the 1882 Western Antiquary. Perhaps something to be aware of during this period of climate change. ‘When Caradons capped and St Cleer hooded, Liskeard town will soon be flooded’. What it means and when these two happenings are likely to occur is possibly known to older long-term residents of Liskeard.

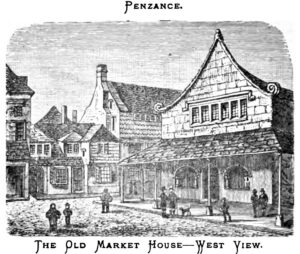

Information relating to Penzance in 1882. ‘The Market House was opened on the 14th of June, 1838. It stands on the site of a group of buildings which were taken down in 1836. The most noteworthy of these was the Old Market House the upper floor of which formed the Guildhall and Corn chamber the former at the west end, and the latter at the east. It was a grey, and rather gloomy looking old structure, yet not without a certain grace, from an artistic point of view. The lower floor the meat-market was lighted through arched apertures of rather handsome construction, the arches resting upon two short pillars, the whole being of granite. One of these windows may now be seen in the grounds of York House, where it forms an entrance to the fruit gardens. The Market-house was surrounded on three sides by a heavy penthouse roof, supported on pillars, underneath which, or around it in portable covered stalls such as we still see on Fair-day, the market folk offered their goods. The chief entrance to the Market-house and Guildhall was on the north side, Just opposite where the Golden Lion Inn now is. It was approached by a semi-circular flight of steps, and over the door appeared the town arms, which were sculptured by Mr. Isabel, of Truro. This same medallion is now above one of the north entrances of the present Market-house, though in that portion of the building, which was originally constructed for a Guildhall, with its council chamber, offices, and watch-house, and over the door of the latter it was placed. This bit of carving seems to have superseded an older piece of work at a time when a spirit of improvement seized upon the inhabitants of Penance.’

Still taking place today is the ‘snail creep’ dance including as part of the recent Rescorla Festival. W C Wade wrote in 1882; ‘At Roche, and in one or two other adjacent mid-Cornwall parishes, a curious dance is performed at their annual " feasts," and which, I am of opinion, is of very ancient origin. It enjoys the rather undignified name of the Snail Creep but would more properly be called the ‘Serpent's Coil.’ The following is scarcely a perfect description of it. The young people being all assembled in a large meadow, the village band strikes up a simple but lively air, and marches forward followed by the whole assemblage, leading hand in hand (or more closely linked in case of engaged couples), the whole keeping time to the tune with a lively step. The band, or head of the serpent, keeps marching in an ever-narrowing circle, whilst its train of dancing followers becomes coiled around it in circle after circle. It is now that the most interesting part of the dance commences, for the band, taking a sharp turn about, commences to retrace the circle, still followed as before, and a number of young men with long leafy branches of trees in their hands as standards, direct this counter-movement with almost military precision. The lively music, and the constantly repassing couples make this a very exhilarating dance, and no rural sports of which our poets treat could be more thoroughly enjoyable. Is this dance a relic of the Saxons, Romans, or old Britons? I do not remember ever reading of any similar dance, or of any reference to the above.’

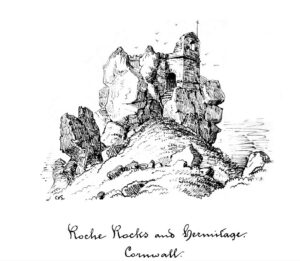

The village of Roche is perhaps best known for the historic monument known to most people as Roche Rock when they actually mean the medieval hermitage or chapel perched high up on it. This famous feature is the ruins of the chapel dedicated to St Michael and was the subject of many comments in several editions of the monthly Western Antiquary. Already a ruin in 1882 it has sadly grown somewhat more ruinous over the subsequent 140 years. The reasons for originally constructing the chapel high on this rocky outcrop are shrouded and lost to history although we know a dedication of the chapel to St Michael took place on 16th September 1409. The historian Charles Henderson believed this followed the rebuilding of the chapel indicating that it may have been built far earlier. Those providing information to the Western Antiquary retold the various tales of hermits and lepers, who actually may have inhabited the chapel, along with other fantastical stories which have added to its tales and myths.

Is Roche really named after the prominent rock on which the chapel was built, standing within the historic Manor of Tregarrick? This was once owned by the de Rupe family during the 12th century, who were also known as de la Roche meaning of the rock, Rupe being the Latin version of rock. Originally Flemish, coming over with William I they were also the builders of Roch Castle in Pembrokeshire during the late 12th century. It is likely that the village and parish took the name Roche from the family who controlled it from the 12th century rather than perhaps the other way round as is often the case. Maybe just a massive coincidence that there is this large rocky outcrop nearby on which the de Rupes were the likely builders of the chapel there. John Norden travelling around Cornwall in the late 16th century mentions the rock and the chapel extensively, of the chapel; ‘ Arte, which raysed a buylding vpon so cragged a foundation’. Richard Carew in 1602 talks of the hermit ‘who dwelt on the top thereof, were it but in regard of such uneasy climbing to his cell and chapel, a part of whose natural walls is wrought out of the rock itself.’

Still a place of attraction and interest today, much has been written since contributors to the Western Antiquary in 1882 added their two pennyworth to its myth.

![Snail Creep at Rescorla 1900's [courtesy of Cornish Audio Visual Archive] Snail Creep at Rescorla 1900's [courtesy of Cornish Audio Visual Archive]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Snail-Creep-at-Rescorla-1900s-courtesy-of-Cornish-Audio-Visual-Archive.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 19.07.2023 [1] Antique books share stories](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Ertach-Kernow-19.07.2023-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 19.07.2023 [2] Antique books share stories](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Ertach-Kernow-19.07.2023-2-254x300.jpg)

![[160] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 19th July 2023 - Charlestown & Cornish Lifeboat exhibitions, Lostwithiel Museum walk Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 19th July 2023 - Charlestown & Cornish Lifeboat exhibitions, Lostwithiel Museum walk](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/160-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-19th-July-2023-Charlestown-Cornish-Lifeboat-exhibitions-Lostwithiel-Museum-walk.jpg)