Ertach Kernow - Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall

The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall as the main title of a book written by the Reverend John Whitaker and published in 1804 might on the face of it be considered a misnomer. This isn’t about Truro Cathedral, which isn’t that ancient and wasn’t built for nearly another eighty years, but a history of Cornwall’s early 11th century church cathedral. There is also much general history of Cornwall as was understood at the beginning of the 19th century. It was during this century that so much changed. However, works of this period do give modern folk an idea of what peoples thoughts were and what they believed before the great scientific discoveries of the Victorian age. These books also provide information about churches, monuments and other edifices before the zealous Victorians swept so much away in their reconstructions and refurbishments destroying valuable historical evidence.

Born in Manchester in 1735 John Whitaker studied at Oxford. After receiving his qualifications with a Batchelor of Arts, Master of Arts and Batchelor of Divinity he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1771. He became Rector of Ruan Lanihorne parish in 1778 and remained rector there for 30 years until his death at the Rectory in 1808. His first work was a history of Manchester in 1771, which at that time had a population of 25,000 and growing rapidly. Apart from his final work ‘The Life of Saint Neot, the Oldest of all the Brothers to King Alfred’ published after his death in 1809 the last major work was ‘The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall’ in two volumes. Whitaker also made contributions to Richard Polwhele’s ‘History of Cornwall’ published in 1803.

As always click the images for larger view

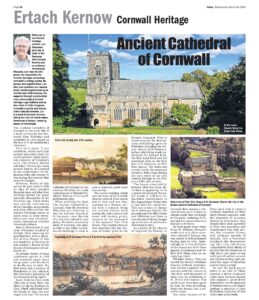

When entitling his book The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall, what the Reverend Whitaker was referring to was the historic church at St Germans, once the site of a Cornish cathedral and priory. He writes extensively about St Germans, the saint, as well as the wider ecclesiastical buildings in what is now a relatively quiet rural community. The earlier building which was the home of the Cornish diocese existed from about 926 to 1030 and was later replaced by a Norman priory with a remnant being the current church built during the 13th century and some 12th century priory remains in the basement of the adjacent Port Eliot House. The Cornish diocese was absorbed into the Diocese of Exeter prior to the Norman Conquest

What is interesting are the descriptions of buildings given by Whitaker, including the former rectory at St Germans, before rebuilding work undertaken for Edward Eliot, the first Lord Eliot and his successor John as the first Earl of St Germans, on Port Eliot House. The work was carried out by the renowned architect John Sloan during the later years of the 18th century through to the first years of the 19th century. The house inherited by Edward Eliot has been described as appearing ‘to be a grand old mansion house, but inside it still bore remarkable resemblance to the Augustinian Priory that it had been for centuries.’ This was a time of change for St Germans Church, the grounds and Port Eliot House and Whitaker was there to record some of those changes up to the date of publication of his book in 1804.

As a rector of the Church of England his history of Cornwall does contain a substantial amount of content on various saints that are linked to Cornwall, including St Piran and his connections as a disciple to St Petroc. He does quote some items from Dr William Borlase’s works and very often somewhat critical of Borlase who was unable to defend himself having died in 1772. Interestingly he is very defensive of the reputation of St Piran against accusations and beliefs of St Piran shall we say enjoying a tipple. Whitaker writes; ‘This oral record the Doctor (Borlase) repeats without reprehension; without suspicion; thus, concurs with the tinners in 'the folly and falsehood of their zeal, by attributing to St. Piran information that could never have been given by him, by even moulding. their holy hermit into a scientific miner. But these votaries of St. Piran have lent at times a contrary direction to their fancy-formed registers; with the stupidity of drunken tinners in their prate, have shaped their saint agreeably to their own practices; and transformed that holy hermit, that venerable bishop, that primary apostle of Ireland, into a wretched drunkard like themselves; nay, this very sottishness [stupefaction from drink] of ebriety, like the falsehood of folly above, has made its way to the pen of, authors as weak and vicious as they, and polluted the pages of literature with its black current.’ So, was the myth passed down to us that St Piran enjoyed a drink originally come from Cornish miners who enjoyed a good drink themselves?

As we approach St Patricks Day on 17th March perhaps a mention of John Whitakers inclusion of this Celtic saint in his work. Whitaker writes; ‘That the Britons of Cornwall drew the attention of St. Patrick, that way; that he halted a little on the shores of Cornwall; yet is said to have built a monastery there; that the Britons of Cornwall drew him into the country, by persisting in their druidism, yet he halted but a little among them; built a monastery, but made no converts; that, however, he actually came merely to visit his preceptor the blessed Germanus, and actually staid some time with him.’ There is no real evidence that there was a druidic cult here in Cornwall, albeit what could be termed Celtic pagan religion undoubtably did exist. Those that practice non-Christian religions outside today’s other major religions and certainly during the early days of Christianity were by the middle ages termed pagans. Whitaker believes that although St Patrick may have visited Cornwall he did not build a monastery and belief he did is through an erroneous confusion of St Patrick with St Petroc one of Cornwall’s patron saints popular here during medieval times.

Of ancient times and monuments Whitaker referred to Carne Beacon at Veryan. ‘This fortress has even assumed all the importance which Din-Gerein itself once possessed, of communicating its own name to the port under it; the last being denominated even to these later days, Gwindruith, or Gwyndraith bay, the bay of the white sand. Here therefore I apprehend the son of Gerein to have resided, at the death of his royal father; and hither I believe him to have transferred the remains of the king, in order to bury them in that great barrow near the Borough-close, which is so apparently from its size the sepulchre of a king. It is one of the largest barrows in England, being about 372 feet in circumference at the base, while that amazing mass of accumulated mould, Silbury-hill, is only about 500. It was originally called the Carne, as the estate enclosing it is still denominated Carne, and as it is popularly styled itself at present from a beacon erected upon it, Carne Beacon; the appropriated term for a barrow being still Carn in Welsh. In analogical strictness, indeed. Carne signifies one made of accumulated stones, so shews this kind of barrows to be prior in time to any other, but in use and practice imports also one composed of earth, like this.’

King Arthur also pops up time and time again and interestingly Whitaker mentions the hillfort at St Dennis, which now contains the church of St Deny’s within it. Much of what he writes regarding Arthur is based on the works of the monks Gildas from the sixth century and ninth century Nennius as well as the Ecclesiastical History of the English People written by the Venerable Bede in the eighth century. The works of these writers has been mentioned before in Ertach Kernow articles, some of which is dubious, or in Bede’s case very biased towards the Anglo-Saxon cause.

Whitaker lived during a period of Cornwall’s history where our culture and especially the Cornish language was fast disappearing. The final few nails added to the coffin of Kernewek during Tudor times as Whitaker commented. ’The English Liturgy was not desired by the Cornish, but forced upon them by the tyranny of England, at a time when the English language was yet unknown in Cornwall. This act of tyranny was at once gross barbarity to the Cornish people, and a death blow to the Cornish language. Had the liturgy-been translated into Cornish, as it was into Welsh, that language would have been equally preserved with this to the present moment. He was right, and now countless English books have been translated into Kernewek, including the Bible, with many original new books written firstly for the Cornish language.

Throughout ‘The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall’ Whitaker makes reference to the Cornish language and the meaning of various place names as well as the history of various communities, buildings and people, including saints. Through modern research, archaeology and scientific discovery there is much of the Reverend Whitakers work that has now proved incorrect. However, there are also some very curious pieces of information now lost to time and for those suffering from insomnia or with the time or to pick them out from this rather rambling verbose work they could prove very interesting and informative. Chons da!

![[194] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 13th March 2024 - Spirit of Cornwall, ‘Music of the Roseland’, Lowender Celtic Mus Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 13th March 2024 - Spirit of Cornwall, ‘Music of the Roseland’, Lowender Celtic Music](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/194-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-13th-March-2024-Spirit-of-Cornwall-‘Music-of-the-Roseland-Lowender-Celtic-Mus-285x300.jpg)