Ertach Kernow - Evolving archaeology and new Cornish discoveries

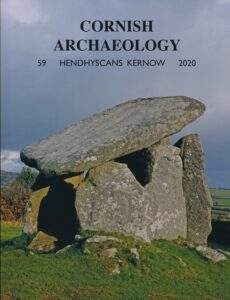

Evolving archaeology and new Cornish discoveries. The British Archaeology Festival begins on 19th July and there’s still time to submit your Cornish archaeological activity. This will enable the group to use resources available on the Council for British Archaeology's website. For what is a relatively limited area Cornwall is very well endowed with archaeology and groups involved, with continuous new discoveries being made. The Cornwall Archaeological Unit now known as Cornwall Council Historic Environment Service is at the forefront of these. The Cornish Archaeological Society is a charitable organisation with around five hundred members carrying out a multitude of projects within the heritage sector.

Besides these there are numerous medium and smaller localised groups and societies throughout Cornwall investigating, researching, sharing and carrying out clearance work. The later is so important to ensure invasive plants don’t destroy what archaeology still remains. The festival creates opportunities for voluntary groups to focus to make the general public aware of the fantastic work they are doing in preserving Cornwall’s archaeological landscape and heritage. This year’s British Archaeology Festival theme is ‘Archaeology and Wellbeing’. Involvement in projects, getting to meet people and be involved in activities can be good for peoples mental health. Besides this festival period there’s always lots of year-round archaeological activities here in Cornwall.

As always click the images for larger view

John Aubrey is acknowledged as perhaps the first British pioneering archaeologist. He is recognised by having the ‘Aubrey holes’ named after him for aspects of Stonehenge’s archaeology. His systematic examination of the Avebury henge was particularly groundbreaking. He visited and recorded substantial numbers of megalithic structures and field monuments in southern England and Cornwall. Two particularly noted by Aubrey were the stone circle at Boscawen-Un and King Doniert’s Stone near St Cleer. The 17th century was before any understanding of the date of the earth and its prehistoric dateline. Considering anything possibly pre-Roman was deemed somewhat adventurousness and evolving story of druids began to do the rounds.

Although people such as John Leland and John Norden had visited many sites in Cornwall, even drawing them in some detail, they were not considered archaeologists. Leland was an antiquary and Norden was a cartographer and antiquary. Although ancient constructions were interesting to them it was still too early for archaeology to find a scientific footing in the 16th and early 17th centuries.

Today archaeology is not just about grubbing about in the soil, although this remains probably the most important aspect by extracting artefacts and information. Technology is advancing ever faster even LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) invented shortly after the laser using light waves dates from the early 1960’s. Once fitted to aircraft the 1970 saw it being used in mapping the earths surface. By the 1990’s the archaeological benefits were being appreciated and since then LiDAR is being used to monitor and help protect historic sites. Looking at one small patch of wooded area in Mid-Cornwall the LiDAR map shows beneath the tree foliage a series of what appears to be field systems. Dunmere Wood outside Bodmin has a small ancient hillfort hidden amongst the trees. LiDAR clearly shows the outline of the embankments of this small ancient Cornish archaeological site.

It wasn’t until scientific advances in the 20th century that geophysics really became useful for archaeological purposes with the first British use recorded in 1946. Three variants are magnetometer surveys, earth resistance surveys and Ground Penetrating Radar. These techniques are used prior to any physical groundwork to ascertain whether there is any likely archaeological remains and if further investigation might be required. These investigations are begun if there is suspected archaeology due to the historic nature of the site. An example is of a small area at Nancegollan having an archaeological geophysical survey carried out in 2017 due to planned building work. Quoting the Cornwall Archaeological Unit report it gave the historic reasons for the survey. ‘Pengwedna was first recorded in 1277 and had been subdivided into Higher and Lower Pengwedna by 1400. The neighbouring farm of Huthnance was first recorded in 1289. Taken together with other early farmsteads in the locality, this gives good evidence for this landscape having been settled by at least the time of the Norman Conquest.’ Although some early archaeology was detected only small amounts were within the development area.

Soil geochemistry looks at trace elements in soil as part of an archaeological investigation. This provides clues to how former occupants of the site used the land. Was it enriched for example by the addition of what was known in Cornwall as manure, often meaning sea sand? The trace elements may inform whether the land was used as a midden for waste material. A section of land may have been used for multiple purposes over the centuries and soil geochemistry will help identify some of those. These technologies really help in the continued evolution of archaeological discovery.

King Arthur’s Hall on Bodmin Moor was first mentioned by John Norden in 1584 he wrote ‘Arthures Hall. A place so called and by tradition helde to be a place whereunto that famous K. Arthur resorted: it is a square plott about 60 foote longe and about 35 foote broad, situate on a playne Mountayne, wrowghte some 3 foote into the grounde: and by reason of the depression of the place, their standeth a stange of Poole of water, the place sett rounde aboute with flatt stones in this manner’ he continued by providing a diagram. Later archaeologists and antiquarians believed it to have been a medieval animal pound dated to around the year 1,000 CE. Recent work carried out by the Cornwall Archaeological Unit, who led the project as part of Cornwall National Landscape’s ‘Monumental Improvement’ initiative, changed everything about the understanding of this site.

With fifty-six standing stones and using new techniques to completely redate this site it has now been described as an ‘enigmatic site, which has few parallels in England’ creating worldwide interest. Pollen grains and other small pieces of ancient remains found in the soil has allowed radiocarbon dating to better date the sites construction. A different technique was the use of Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) to date the monument. Whereas radiocarbon dating is used relating to organic material OSL is used to date minerals through finding for example, the mineral's last exposure to sunlight. These technological advances used by the team, including from the University of St Andrews, has proved the age of ‘King Arthur’s Hall’ is some 5,000 years old dating back to the Stone Age Mesolithic period.

Stonehenge in England is well-known but there are also three known surviving henges in Cornwall, Castlewich Henge, the Stripple Stones and Castilly Henge. Excavation work at Castlly organised by Cornwall Heritage Trust, Cornish Archaeological Society and English Heritage will commence in September 2025. There was work carried out on this site back in the 1960’s by eminent Cornish archaeologist Professor Charles Thomas. More recently English Heritage carried out earthwork and geophysical surveys in 2022. Castilly is believed to date from the late Neolithic Stone Age period around 3,000 BCE and used through the later Bronze Age. During the much later medieval period it has been suggested by some researchers that it was used as a plen-an-gwarri for open air theatre. Actually getting into the soil and using modern scientific techniques could prove enlightening just as the finding at King Arthur’s Hall completely changed understanding of that site and its age.

Once again Castilly Henge is one of those sites that needs support from the caring public through volunteers to help with the dig and then afterwards. Like many sites throughout Cornwall our warm and often damp climate does encourage the growth of invasive plants whose roots can breakup hidden archaeology. There will be a large amount of outreach work organised to encourage interest and activity from potential volunteers. This is not just a project for one month and to ensure the long-term safety of this important Cornish archaeological site, biodiversity of the field and overall sustainability will need local people’s support.

Cornwall with its wide variety of ancient monuments could have its early history altered through the use of science redating much of what we currently believe. Another relatively new science being used in archaeology is the use of DNA in dating and finding connections. Cornwall’s acidic soil does not often allow the survival of bones back to ancient times although many from recent centuries have. DNA investigations using surviving ancient bones recently discovered newly discovered Denisovan hominoid’s in 2010 from a small fingerbone fragment. Further DNA advances can now identify what are known as ‘ghost populations’ of ancient human ancestors, where no actual bone remains exist. Through interbreeding of species parts of earlier hominoid ancestry is recorded in DNA and most of us will have a small percentage of identifiable Neanderthal DNA. Wouldn’t it be a wonderful thing if ancient bones could speak to us through science of the movement and existence of earlier peoples here in Cornwall, such as the Beaker folk. Archaeology here in Cornwall is continually adding information to our Cornish heritage and should be encouraged for the knowledge and potential economic benefits.

The British Archaeological Festival begins on 19th August and runs to the 3rd August 2025. Information and resources can be found at www.archaeologyuk.org by clicking ‘Festival’ at the top of the page. If you’re involved with a group, participation and publicity will be good, also helping highlight Cornish archaeology. If not please support a Cornish archaeological group by attending one of their events or activities.