Ertach Kernow - Cornish travels with author Lewis Hind

The next leg of Lewis Hinds Cornish travels would be along the north Cornish coast. Having explored the Tamar Valley and found the source of the River Tamar, Lewis would now see some of Cornwall’s spectacular cliffs and coastal landscapes. Stopping for a night across the Cornwall-Devon border at Bideford, Lewis took a jingle, a small horse drawn carriage with driver, and headed for Welcombe. This was a Devon parish where the Reverend Stephen Hawker had been vicar before he finished his ministry in Cornwall at Morwenstow.

Crossing the upper levels of the Tamar and into north Cornwall Lewis headed for Marsland Mouth. Here he was totally enchanted, writing; ‘What a place! What a valley! With a sleeping sack one could be happy in this green haven for ever, or a week, so sheltered so winning is it.’ He descended to eat his lunch and ‘feast his eyes on that lonely and magnificent valley.’ No doubt very different now but Lewis felt that the valley had not changed much since Charles Kingsley pictured it in his popular novel ‘Westward Ho!’ Lewis had obviously read both Kingsley’s novel as well as Reverend Hawkers ‘Footprints of former men in Cornwall’ as he add quite lengthy quotes from them to illustrate his points.

Thank you for reading the online version of the Ertach Kernow weekly articles. These take some 12 hours each week to research, write and then upload to the website, and is unpaid. It would be most appreciated if you would take just a couple of minutes to complete the online survey marking five years of writing these weekly articles. Many thanks.

Click the link for survey: Ertach Kernow fifth anniversary survey link

As always click the images for larger view

Following instructions to follow the coastguard path from Marsland Mouth to Bude he was persuaded the walk would be easy. He could not find the path, perhaps unused it had become overgrown. Giving up his search he ended up scrambling up low cliffs and through undergrowth whilst carefully avoiding the sea edge cliffs with their dizzying height and boiling surf beneath. Hind makes the point that ‘he who has not walked this section of the north coast cannot imagine the lonely and angry majesty of the sea.’ In his mind whilst overlooking the sea Lewis was thinking about Hawkers talk of Cornish smugglers particularly the notorious ‘Cruel Coppinger’ of which there is probably more myth than truth. About 4:00pm tempted by the thought of some refreshments Lewis wandered from his path towards what he believed was Combe Porth but was actually Stanbury Mouth. Somewhat lost and damp whilst traipsing across waterlogged fields and through woodland he eventually came to a cottage. He wrote ‘there in the cottage I found the usual lonely Cornish woman engrossed in her household duties, kindly, but regarding strangers with an ill-concealed suspicion.’ This woman was not at all talkative but at least put Lewis back on track and towards something to refresh himself at Combe.

Passing the site of Stowe House which he had visited previously Lewis took the coastal route towards the sea rather than the inland path. travelling through orchards and over heathery downs he came to Long Rock. A ‘healthy place of wide sands.’ He thought in time, based on the existence of a rough road leading to the shore, there was the potential of a seaside resort. This is a little to the north of Bude and never developed as Lewis Hind had imagined. There was a cottage selling ginger beer and even today there are the ‘Rustic Tea Rooms’ with some holiday cottages close by. These were perhaps those Lewis saw on his visit to Northcote Mouth and it was now he considered he had re-entered civilisation.

Lewis comments that inland was Poughill and that the town of Bude was growing into a suburban London as seen from Hampstead Heath. Observing Bude Haven, as Bude was known as in those days, he observed that the breakwater was standing ‘bravely forth’ and the lifeboat was out practicing. Apart from mentioning the Falcon Hotel at which he stayed the night Hind makes no further mention of Bude. This is a shame it would have been interesting to hear his views about Bude in the early 20th century. Bude had grown quickly from a small port and village around 1850. Mentioned in Bradshaw’s 1866 Guidebook, it said of Bude it had; ‘within the last half-dozen years, risen to the dignity of a fashionable marine resort, to which distinction the excellent facilities it affords to bathers, and the picturesque scenery of its environs, have in a great measure contributed.’

The Bude Canal completed in 1826 had encouraged a small harbour area, with the breakwater in 1838 to protect the canal entrance. In 1880 the Tregellas ‘Tourist Guide to Cornwall’ says of Bude, ‘a favourite and growing watering-place’, so Bude was on the rise, in time it would overtake the nearby historic town of Stratton. The coming of the railway in 1898 via Holsworthy led to even further expansion of this growing resort. In 1906 the ‘Cornwall Trades Directory’ showed that Bude had a wide range of shops and businesses far wider than you find on today’s high streets. Boarding establishments and hotels listed alongside restaurants and even the ‘Bude Sanitary Steam Laundry’. It was just a year later that Lewis Hind visited Bude.

Leaving Bude Lewis climbed to ‘Compass Point’ on what he described as a ‘sunny fragrant morning’. Descending into Widemouth Bay he told readers, local people hoped it would become the Eastbourne of Cornwall. Oh dear! There was a sign mentioning part of the road having been undermined by the sea and was dangerous to traffic. Erosion on the north Cornish coast was obviously an issue, and I wonder if the sea facing cottages he mentions are still there. Climbing up he rested to enjoy the scenery. Here he mentions seeing in the far distance through the haze Tintagel Castle. Moving on Lewis hoped to reach Crackington Cove by lunchtime and soon descended to Wanson Mouth and up the more difficult climb the on the other side.

Many today enjoy walking the Cornish coastal path, but how different it must have been with fewer manmade improvements in earlier times. Development, construction and lust for mammon have diminished many parts of Cornwall’s landscape, how wonderful to be able to see it in a past age. Although 19th and earlier 20th century writers tended to be wordier than today, their prose allowed one to visualise scenes when images were unavailable. Lewis Hind continues: ‘a walk round the Cornish coast is a succession of surprises. The wayfarer never knows what exhilarating experiences are in store for him, I had just breasted one hillock and was mildly ready for another when a twist of the path that dodged round an outcrop of rock revealed, lying far below, one of the most delightful glens that I had yet seen. Issuing from the recesses of a spinney, the stream raced down it seaward, turning, twisting and spirting over boulders. Two boats were drawn up above the beach, crabbing-pots were scattered around, the cliffs rose sheer on either side, and the rising meadows, through which the stream coursed, were dotted with cottages.’

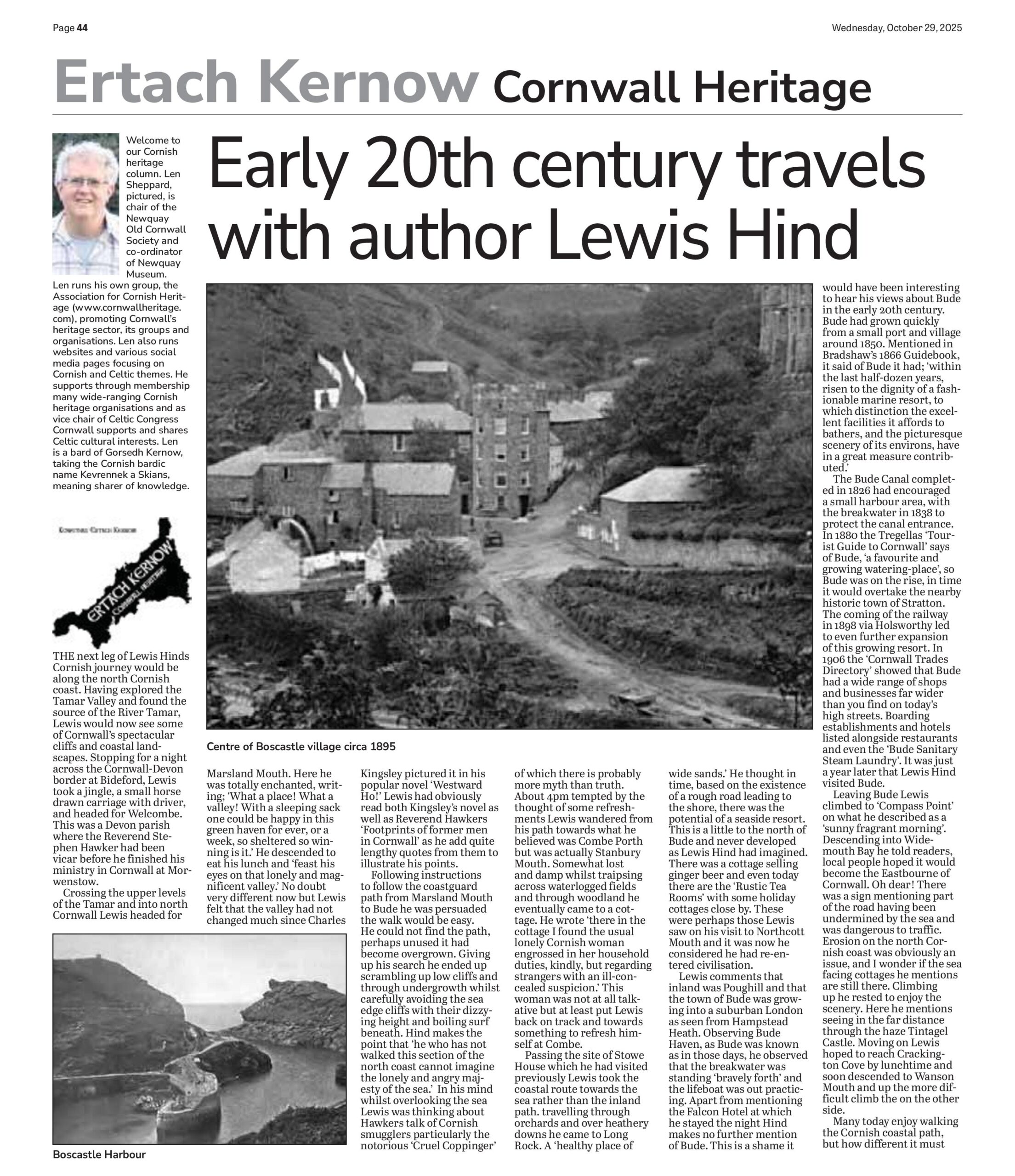

Onwards. Moving inland Lewis asked for directions of Crackington Cove and stopped a while at a farmhouse large enough to be marked on the Ordnance Survey map. From a collection of books he took time to read an account by Reverend Stephen Hawker of a ride from Bude to Boscastle. Lewis was particularly interested in Hawker’s description of Warbstow Bury, written in typical Hawker romantic style. See the Ertach Kernow article number 270 dated 27th August on the website for my recent visit to Warbstow Bury hillfort. Leaving the farmhouse he then writes ‘The approach to Crackington Haven revived my spirits and gave a lilt to my steps. It is a romantic spot, promising all manner of climbs and wanderings over rocks. On the east rises Pencannow Point, a mass of dark slate 400 feet high; to the west is Cambeak (also called Carnbeak) 330 feet high, and between these two headlands lies Crackington Cove. I walked down to the rocks and sat there amid the silence of the unspoilt haven.’

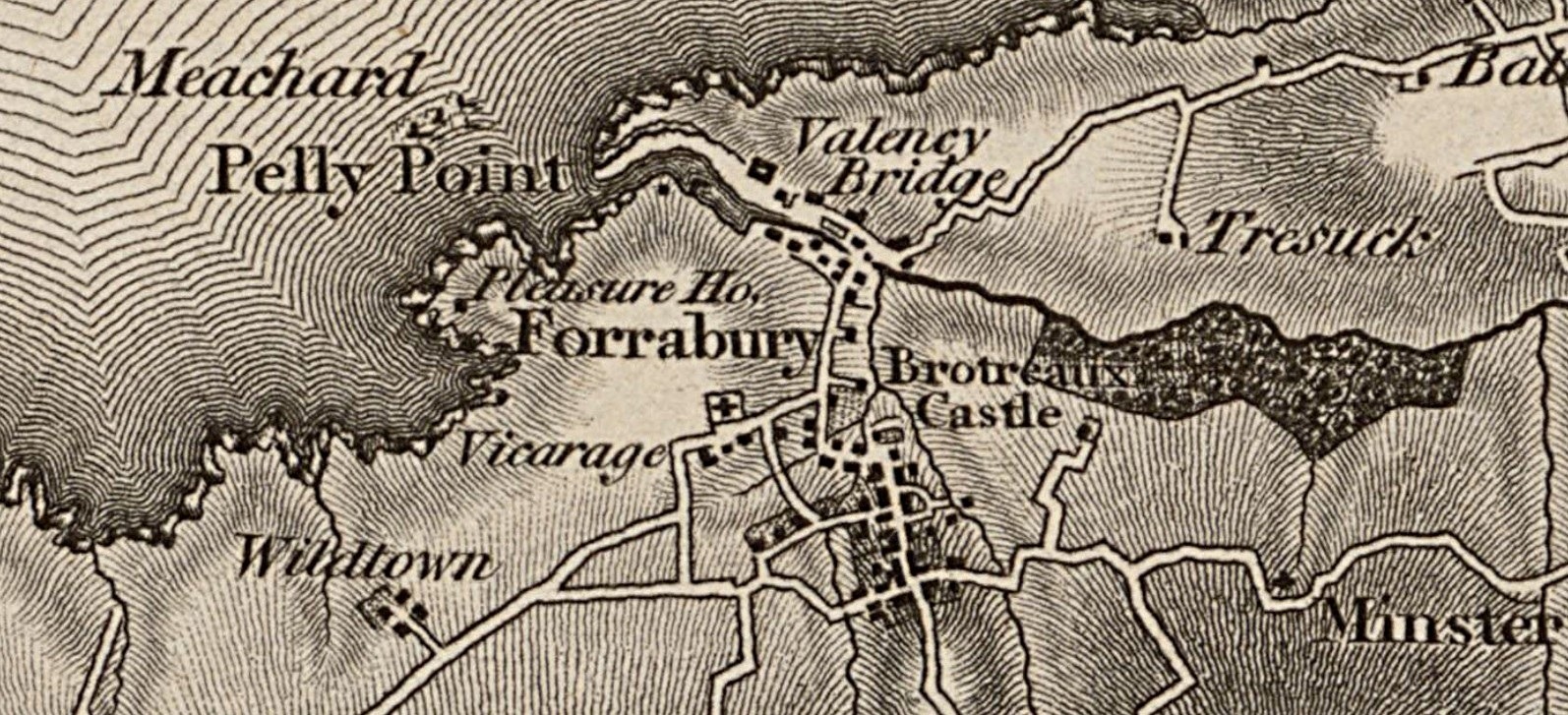

Meeting with a farmer who offered him a lift in his dogcart, a two wheeled horsedrawn vehicle, Lewis made his way towards Boscastle to spend the night. Dropped off at the top of the hill, his previous visits had been made during summer months and the comparison was stark. The summer had seen Boscastle full of tourists, now Lewis noted it was dark and empty and after losing his way was directed to the inn by a kindly stranger. Here he was met by his friend a burly Cornishman who had driven from Camelford. Of the small harbour Lewis mentions; ‘The few vessels that make for Boscastle are warped in by great hawsers or towed through the opening into the harbour by a boat with seven rowers.’ He likely mentions a Cornish pilot gig which has six rowers and a coxswain. Historically pilot gigs had more rowers, but Acts of Parliament limited them to just six. Often used for smuggling during the 18th and 19th centuries with more than six rowers they were often able to outrun the revenue cutters of the customs boat service.

The following day a vessel was heading for Boscastle and a pilot gig set out to guide them in. This was a usual thing around the Cornish coast with their small often difficult harbour entrances. This would be the first vessel of the year Lewis was told. However, it seems the captain of the vessel was unhappy to pay the ‘hobblers’ for their assistance and Lewis never saw if the ship entered the small Boscastle harbour.

Lewis Hind’s journey to Bossiney and then Tintagel will continue in a future article. What will this Edwardian writer make of King Arthur and say about Tintagel long before the archaeological discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries.