Ertach Kernow - Cornish ruins, part of our rich heritage

Cornish ruins can be seen throughout Cornwall. Besides the ancient prehistoric sites there are the historic medieval castles and churches and countless structures from Cornwall’s industrial age. Today there are even those buildings from fairly recent times such abandoned hotels, albeit not open to the public which are entered and recorded by young enthusiasts. This unofficial recording of urban decay might be decried by authorities, but it does make good reading and online viewing.

Moving through Cornish history the ruins of prehistoric sites and settlements can be seen throughout Cornwall. Some you need to pay to see, others like Carn Euny are free to access and enjoy. Besides these settlements there are the huge numbers of monuments and stone circles as well as remnants of huts and field systems as seen on Bodmin moor. Then of course there are the medieval castles at Launceston, Trematon, Restormel. All of these are what is termed shell castles. There were a number of smaller forts such as at Fowey and Polruan which held a chain across the river to prevent access to enemy ships. These were replaced later during the reign of Henry VIII by St Catherines Castle. The best known Henrician castles were at Pendennis and St Mawes, built to prevent access to Carrick Roads and the River Fal all the way to Truro.

The ruins of Tintagel are somewhat different and also constructed it believed for another purpose. Of course nothing to do with King Arthur whatsoever this is what might be termed a vanity project or early folly built by Richard Earl of Cornwall in about 1230. Probably motivated by imaginative stories of King Arthur written by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae during the 12th century, Richard built Tintagel. It provided him with a Cornish connection to Arthur other than his title. Although a defensible location the type of stone used in its construction was not something that would have withstood a siege using medieval trebuchet and catapults for long.

Thank you for reading the online version of the Ertach Kernow weekly articles. These take some 12 hours each week to research, write and then upload to the website, and is unpaid. It would be most appreciated if you would take just a couple of minutes to complete the online survey marking five years of writing these weekly articles. Many thanks.

Click the link for survey: Ertach Kernow fifth anniversary survey link

As always click the images for larger view

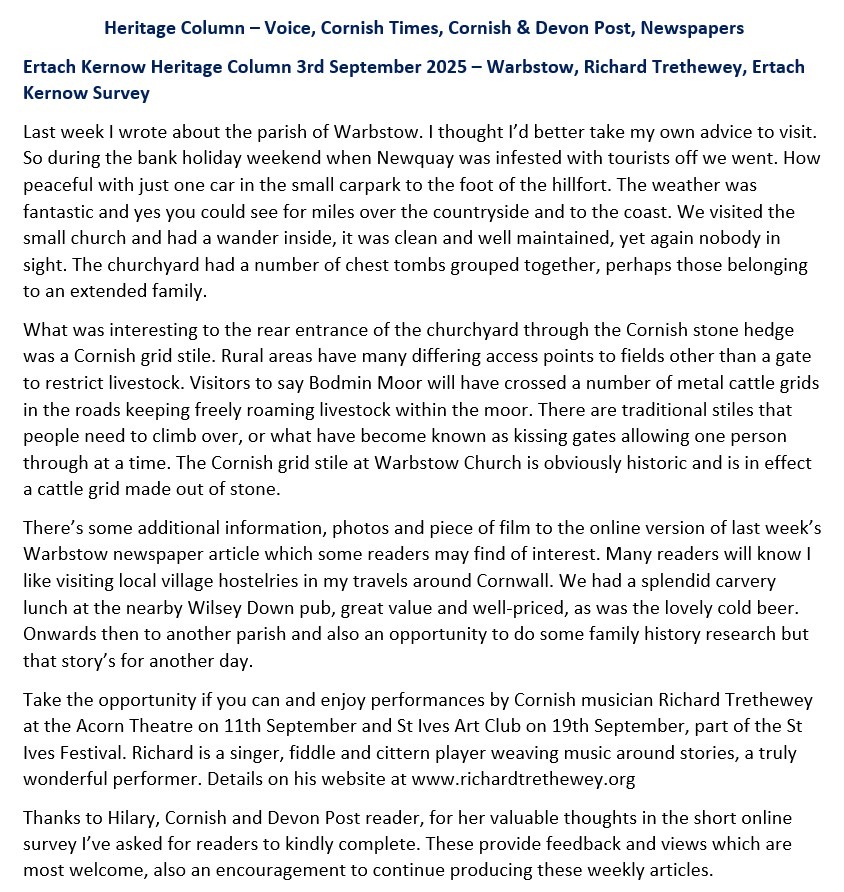

As we move onto the industrial age there are just too many historic mine buildings to mention. Perhaps because they hold an iconic view those at Botallack are of greater interest. The Crown Mines engine houses partway down the cliff where the mineworking extend out under the ocean are a sight to behold. As Duke and Duchess of Cornwall King Edward VII and his wife Queen Alexandria visited the mine in 1865. Other industrial ruins, or at least structures no longer used for their original purpose exist. In good form is the Treffry Viaduct at Luxulyan and within the wood there are remnants of huts, machinery and tramways scattered throughout. These maintained by Cornwall Heritage Trust help keep people mindful of Cornwall’s 18th and 19th century industrialisation.

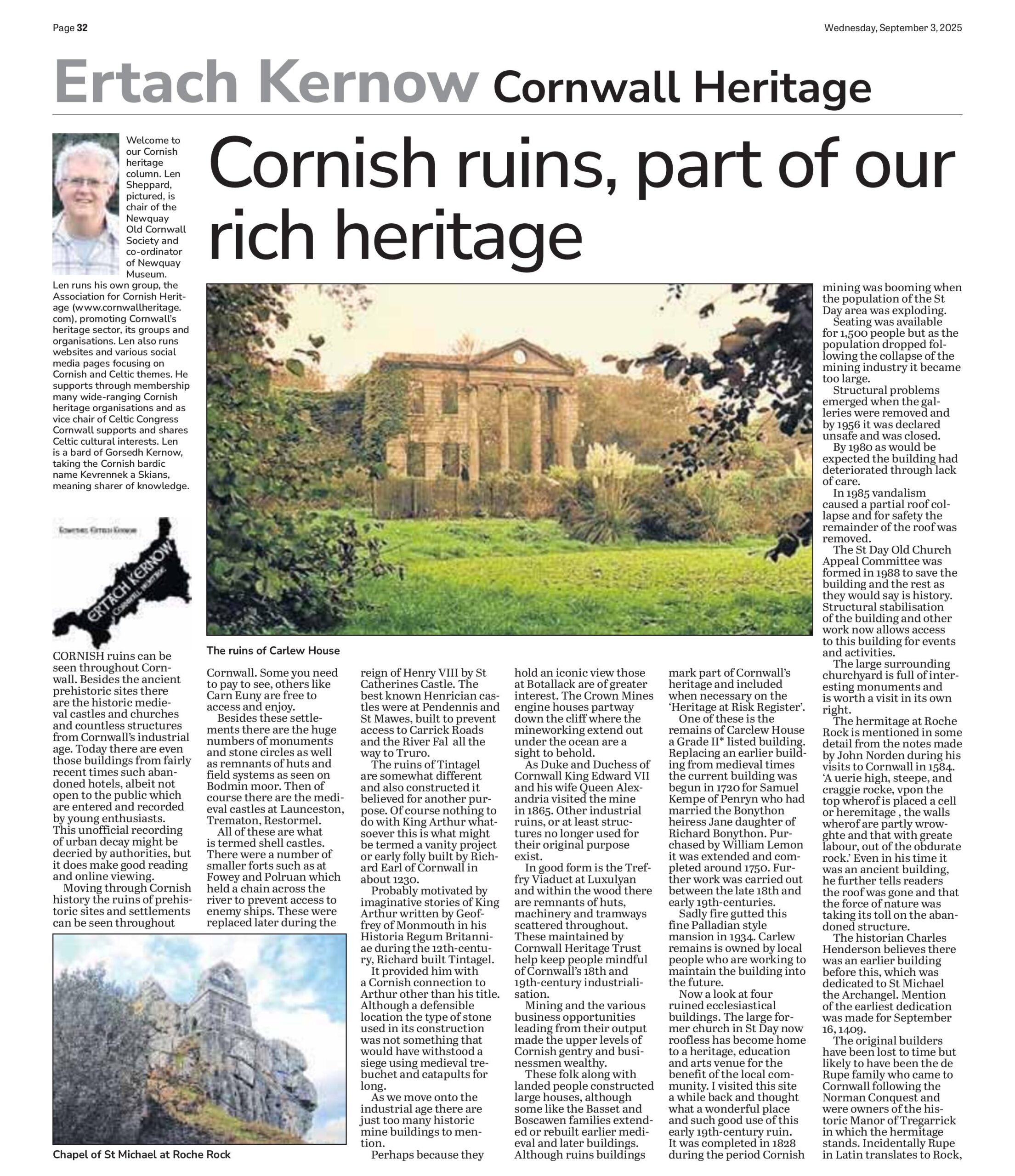

Mining and the various business opportunities leading from their output made the upper levels of Cornish gentry and businessmen wealthy. These folk along with landed people constructed large houses, although some like the Basset and Boscawen families extended or rebuilt earlier medieval and later buildings. Although ruins buildings mark part of Cornwall’s heritage and included when necessary on the ‘Heritage at Risk Register’. One of these is the remains of Carclew House, near Mylor, a Grade II* listed building. Replacing an earlier building from medieval times the current building was begun in 1720 for Samuel Kempe of Penryn who had married the Bonython heiress Jane daughter of Richard Bonython. Purchased by William Lemon it was extended and completed around 1750. Further work was carried out between the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Sadly fire gutted this fine Palladian style mansion in 1934. Carlew remains is owned by local people who are working to maintain the building into the future.

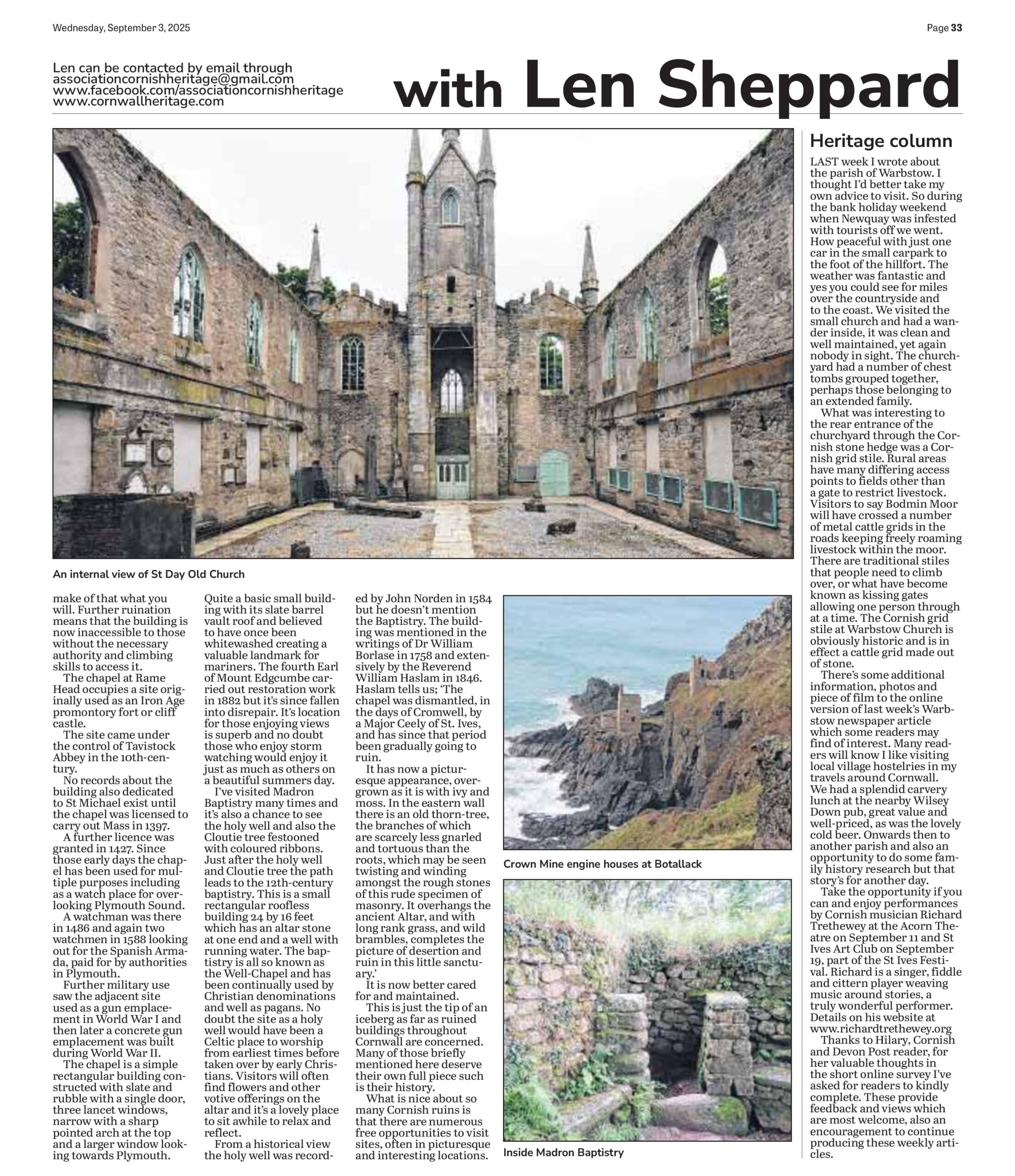

Now a look at four ruined ecclesiastical buildings. The large former church in St Day now roofless has become home to a heritage, education and arts venue for the benefit of the local community. I visited this site a while back and thought what a wonderful place and such good use of this early 19th century ruin. It was completed in 1828 during the period Cornish mining was booming when the population of the St Day area was exploding. Seating was available for 1,500 people but as the population dropped following the collapse of the mining industry it became too large. Structural problems emerged when the galleries were removed and by 1956 it was declared unsafe and was closed. By 1980 as would be expected the building had deteriorated through lack of care. In 1985 vandalism caused a partial roof collapse and for safety the remainder of the roof was removed. The St Day Old Church Appeal Committee was formed in 1988 to save the building and the rest as they would say is history. Structural stabilisation of the building and other work now allows access to this building for events and activities. The large surrounding churchyard is full of interesting monuments and is worth a visit in its own right.

The hermitage at Roche Rock is mentioned in some detail from the notes made by John Norden during his visits to Cornwall in 1584. ‘A uerie high, steepe, and craggie rocke, vpon the top wherof is placed a cell or heremitage , the walls wherof are partly wrowghte and that with greate labour, out of the obdurate rock.’ Even in his time it was an ancient building, he further tells readers the roof was gone and that the force of nature was taking its toll on the abandoned structure. The historian Charles Henderson believes there was an earlier building before this, which was dedicated to St Michael the Archangel. Mention of the earliest dedication was made for 16th September 1409. The original builders have been lost to time but likely to have been the de Rupe family who came to Cornwall following the Norman Conquest and were owners of the historic Manor of Tregarrick in which the hermitage stands. Incidentally Rupe in Latin translates to Rock, make of that what you will. Further ruination means that the building is now inaccessible to those without the necessary authority and climbing skills to access it.

The chapel at Rame Head occupies a site originally used as an Iron Age promontory fort or cliff castle. The site came under the control of Tavistock Abbey in the 10th century. No records about the building also dedicated to St Michael exist until the chapel was licenced to carry out Mass in 1397. A further licence was granted in 1427. Since those early days the chapel has been used for multiple purposes including as a watch place for overlooking Plymouth Sound. A watchman was there in 1486 and again two watchmen in 1588 looking out for the Spanish Armada, paid for by authorities in Plymouth. Further military use saw the adjacent site used as a gun emplacement in World War I and then later a concrete gun emplacement was built during World War II.

Rame Chapel is a simple rectangular building constructed with slate and rubble with a single door, three lancet windows, narrow with a sharp pointed arch at the top and a larger window looking towards Plymouth. Quite a basic small building with its slate barrel vault roof and believed to have once been whitewashed creating a valuable landmark for mariners. The fourth Earl of Mount Edgcumbe carried out restoration work in 1882 but it’s since fallen into disrepair. It’s location for those enjoying views is superb and no doubt those who enjoy storm watching would enjoy it just as much as others on a beautiful summers day.

I’ve visited Madron Baptistry many times and it’s also a chance to see the holy well and also the Cloutie tree festooned with coloured ribbons. Just after the holy well and Cloutie tree the path leads to the 12th century baptistry. This is a small rectangular roofless building 24 by 16 feet which has an altar stone at one end and a well with running water. The baptistry is all so known as the Well-Chapel and has been continually used by Christian denominations and well as pagans. No doubt the site as a holy well would have been a Celtic place to worship from earliest times before taken over by early Christians. Visitors will often find flowers and other votive offerings on the altar and it’s a lovely place to sit awhile to relax and reflect. From a historical view the holy well was recorded by John Norden in 1584 but he doesn’t mention the Baptistry. The building was mentioned in the writings of Dr William Borlase in 1758 and extensively by the Reverend William Haslam in 1846. Haslam tells us; ‘The chapel was dismantled, in the days of Cromwell, by a Major Ceely of St. Ives, and has since that period been gradually going to ruin. It has now a picturesque appearance, overgrown as it is with ivy and moss. In the eastern wall there is an old thorn-tree, the branches of which are scarcely less gnarled and tortuous than the roots, which may be seen twisting and winding amongst the rough stones of this rude specimen of masonry. It overhangs the ancient Altar, and with long rank grass, and wild brambles, completes the picture of desertion and ruin in this little sanctuary.’ It is now better cared for and maintained.

This is just the tip of an iceberg as far as ruined buildings throughout Cornwall are concerned. Many of those briefly mentioned here deserve their own full piece such is their history. What is nice about so many Cornish ruins is that there are numerous free opportunities to visit sites, often in picturesque and interesting locations.