Ertach Kernow - Kilkhampton a story of Hero's Villains and Anarchy

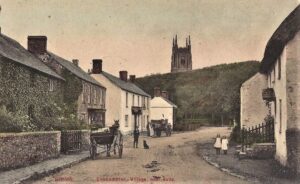

Kilkhampton's story of hero's villains and anarchy is this week’s subject of Ertach Kernow. Not the crater named that on Mars in 2019, but the village to the northeast of Cornwall close to the Devon border. Perhaps not somewhere many in Cornwall have visited as it is on the lesser used A39, which is believed to have been originally a Roman road and as such would have continued to be an important entry to Cornwall in later centuries. As infrastructure building has continued throughout Cornwall, especially on the new works between Carland Cross and Chyverton, there is increased indication of Roman activity. There have been suggestions that there may have been some Roman works around where the church now stands at Kilkhampton, but no substantial evidence has been found, which grave digging may have unearthed.

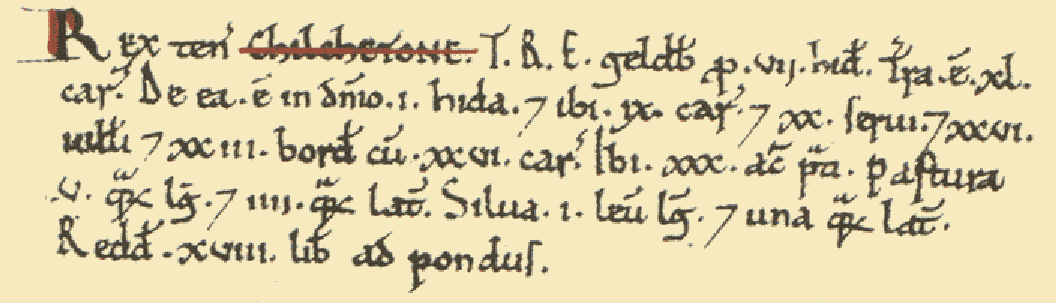

Kilkhampton has deep historic roots with a history that goes back to between 815 and 839 when land at Kelk was given by King Egbert of Wessex to the bishopric of Sherbourne. This probably followed the defeat of the combined Cornish and Danish forces at the Battle of Hingston Down in 838. Following the subsequent defeat of the Anglo-Saxon forces by the Normans at Hastings in 1066 ownership once again moved on and in the Domesday Book of 1086 the land is recorded as being under the control of William I, but prior to that King Harold as Earl Harold. Recorded in Domesday as Chilchetone, it had a population of 69 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

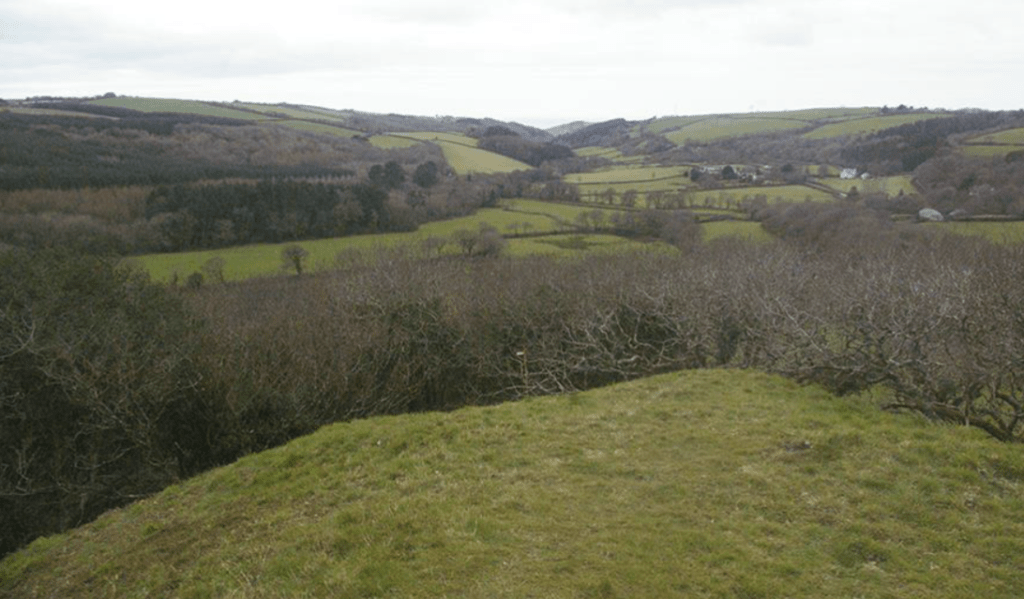

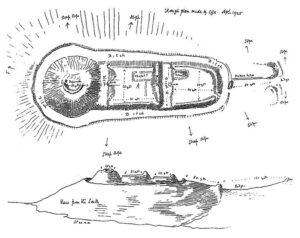

Later it would seem that others felt it was an important area that needed some military control, as outside Kilkhampton are the remains of what was Kilkhampton Castle, also known as Penstowe Castle. This scheduled monument are the remains of an early mott and bailey castle, which was built it is believed during the period known as the Anarchy in the 12th century. Following the death of King Henry I, without a male heir, his daughter Matilda, also known as Maud, to whom most barons had sworn fealty tried to retain the throne. A civil war ensued with her cousin Stephen of Blois, also a grandson of William the Conqueror, eventually winning the kingship, but on his death Matilda’s son became King Henry II. It was during this period that a number of castles were constructed without authority from the king, these became known as adulterine castles, a number being built in Cornwall. All that remains of this castle now are the earthworks which have had a number of archaeological investigations including the latest in 2021. Robert of Caen Earl of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of Henry I, had become tenant in chief of the manor of Kilkhampton at some point early in the 12th century. Perhaps it was he who had constructed this fortress during his support for his half-sister Matilda. Interestingly this castle besides the mott had two baileys.

As with several areas of Cornwall certain families dominated for many centuries and the hundred of Stratton which included Kilkhampton was no exception. In other Ertach Kernow articles the name Grenville has appeared on a number of occasions and it is around the Kilkhampton area the Grenville’s are best represented and memorialised. The Grenville’s are believed to have originally come over in 1066 with William of Normandy and settled in Bideford before acquiring land at Kilkhampton through a family relationship with Robert Earl of Gloucester.

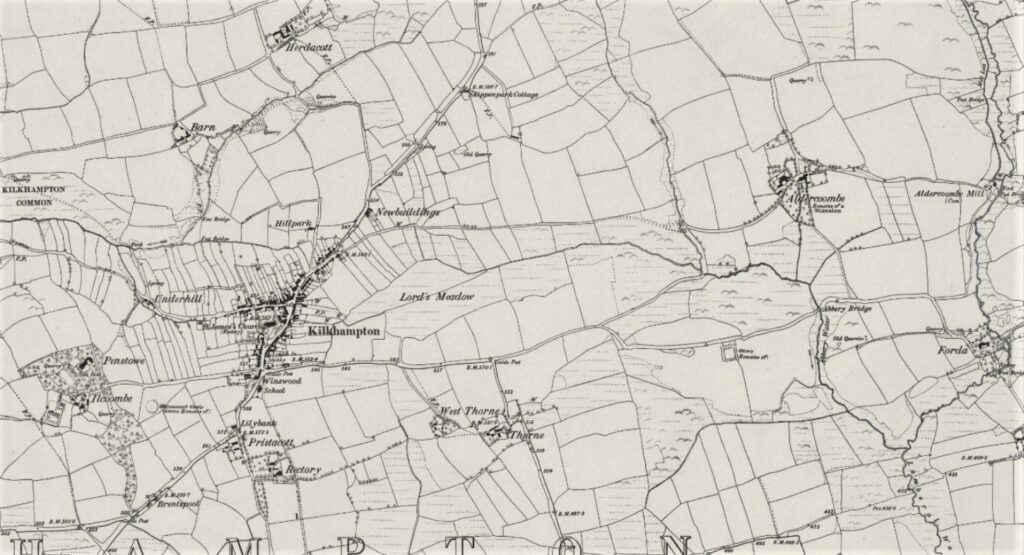

Historic records and archaeology show that by the 14th century Kilkhampton was a well-developed community with enclosed strip field system running up to the outskirts of the village. Later some of these would evolve further into burgage plots within the village, something seen in many medieval towns and villages. Often not seen by those from the road burgage plots are properties facing the streets with long stretches of land to the rear of the property. Many of these can still be seen on the late 19th century Ordnance Survey Map.

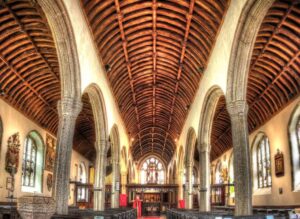

The Church of St James the Great had been constructed at Kilkhampton during the 12th century with the surviving Norman doorway giving some indication to its quality. This doorway has been attributed by some historians to the existence of a monastic settlement at Kilkhampton at the time of its ownership by the Abbey at Tewksbury. Charles Henderson, the Cornish historian, commented it is probably one of the best pieces of Norman work in Cornwall. Rebuilt by the Grenville’s from the 15th century the final addition to the church in 1567 was the south porch that protects the historic Norman doorway, bearing the initials of John Grenville rector at that time. John was obviously a pragmatic man as he held the benefice for fifty-six years during a period of intense religious turbulence and change. Henderson confidently asserts that the tower and much of the church date from this time due to the roodloft staircase and the wonderfully carved bench ends. Sadly, all the Grenville monuments prior to 1700 were destroyed, probably during the construction of Stowe House in the late 17th century.

In 1202 the Abbott of Tewksbury, who was patron of the rectory presented it to the Grenville’s. In 1238 The Abbott of Tewksbury granted the right make an appointment to the benefice, a church living, to Robert de Greynvil. The Grenville’s it seems were not particularly good at choosing rectors acceptable to the bishop, which caused ongoing issues. Henderson relates a story of dispute between Sir Theobald de Grenville and Sir John de Raleigh relating to two clerks. Although Bishop Grandisson of Exeter favoured the clerk wanted by Ralegh, but possession was held by Grenville’s man. Although the Abbot of Hartland and Prior of Launceston were charged with resolving the issue, they failed. On attempting to visit the church at Kilkhampton they were intercepted by armed men who threatened and chased them for over a mile. The Abbot and Prior adjourned to churches at Launcells, Stratton and Poughill and then published a sentence of excommunication against the men of Kilkhampton. The church at Kilkhampton having been fortified by Grenville, his man Merton and an armed retinue the parish of Kilkhampton was placed under an ecclesiastical interdict. During a period of ecclesiastic authority ultimately Sir Theobald had to present himself as a penitent and ask for absolution, making a public confession albeit in French.

Besides ecclesiastic issues there were those of a secular nature. In 1301 when summonsed to show proof of authority to hold markets, usually granted by the king, Richard Grenville stated that a market had been held along with its privileges for time immemorial as well as three annual fairs. From 1306 it was treated as a borough although held no official charter of burghal privileges. The Grenville’s had climbed their way to important positions and Thomas Grenville, probably the first to settle at Stowe became Sheriff of Cornwall in 1480 under Edward IV and again in 1485 in the first year of the reign of Henry VII. His son Richard also became Sheriff of Cornwall as well as Robert Grenville who was Sheriff of Cornwall three times during the reign of Henry VIII. Perhaps less fortunate was Sir Roger Grenville who was captain of the Mary Rose when it sank in the Battle of the Solent in 1545.

Sir Roger’s eldest son and heir was Sir Richard Grenville who met a far more illustrious end. Taking part in the repulse of the Spanish Armada he also served as a member of parliament and Sheriff of Cornwall. He is best remembered as Captain of the Revenge who in 1591 fought a Spanish fleet against overwhelming odds but allowing other ships to escape. He was the grandfather of Sir Bevil Grenville of Civil War fame who led a contingent of the Cornish royalist army and is memorialised in Kilkhampton Church. Sir Bevil’s son John, born in Kilkhampton, would later be created the first Earl of Bath by Charles II after the Restoration in 1660. John’s son Charles inherited the earldom and lands and had one son by his second marriage named William Henry. Charles himself met an unfortunate end whilst preparing for his father’s funeral by accidently shooting himself whilst inspecting a pistol. His body along with his father was brough to Kilkhampton and both were buried on the same day 22nd September 1701. William Henry died aged just 19 of smallpox in 1712 and the earldom became extinct as he had no male heirs and the Grenville family interest in Kilkhampton ceased. The land passed in turn to the Thynne family ancestors of the current Marquis of Bath.

From Norman times the Grenville family had seen Kilkhampton develop into a relatively wealthy market town. The later lack of a powerful and wealthy family with local interests saw Kilkhampton perhaps not develop as it may have done once they had left the scene. However, Kilkhampton is a very pleasant village with a 15th century Inn, called the New Inn, offering a range of traditional Cornish ales and cider. Heritage mixed with an attractive local pub serving Cornish beverages, what’s not to like?

![Sir Richard Grenville [National Portrait Gallery] Sir Richard Grenville [National Portrait Gallery]](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Sir-Richard-Grenville-National-Portrait-Gallery-205x300.jpg)

![[118] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 280922A Hero's Villans and Anarchy [S] Ertach Kernow - Kilkhampton a story of Hero's Villans and Anarchy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/118-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-280922A-Heros-Villans-and-Anarchy-S-241x300.jpg)

![[118] Voice - Ertach Kernow- 280922B Hero's Villans and Anarchy [S] Ertach Kernow - Kilkhampton a story of Hero's Villans and Anarchy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/118-Voice-Ertach-Kernow-280922B-Heros-Villans-and-Anarchy-S-238x300.jpg)

![[118] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 28h September 2022 - Krowji Fun Palace Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 28h September 2022 - Krowji Fun Palace](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/118-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-28h-September-2022-Krowji-Fun-Palace-286x300.jpg)