Ertach Kernow - Cornwall’s geological legacy

Cornwall ‘s geological legacy has in multiple ways dictated its history and culture with its mixture of igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks all within a relatively small area.

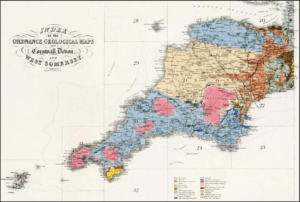

The name of Henry Thomas De la Beche, pronounced Beach, is perhaps unknown to most people outside geological and mineralogical circles. De la Beche was born in 1796 and became interested in geology when living in Lyme Regis through his friendship with Mary Anning, famous for her interest in fossil collecting. It was Anning’s findings which contributed to a sea change in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth. Henry undertook a number of overseas geological mapping projects whilst benefiting from his families interests in plantations in Jamaica. He later became secretary of The Geological Society of London, which had been founded in 1807 and in due course a Vice President. He had taken a special interest in Cornwall and the Southwest counties of England in respect to their geological makeup and had begun to produce coloured maps showing the rock and mineral types found there. His work in Devon had led to the creation in 1835 of the Ordnance Geological Survey under the Board of Ordnance. With De la Beche as its first director work on production of geological maps began in earnest with The Geological Survey Act of 1845 providing a legal framework for the whole of Britain and Ireland. Later this would become as it is now known the British Geological Survey.

It has been suggested that whilst working on Devon he had undertaken a preliminary survey of Cornwall and was particularly intrigued by many strange new issues involved in its complex geology. Due to the vast amount of mining and interest in Cornish minerals a huge amount of unpublished documentation had been collected. The economic benefits of having a better understanding was not lost on De la Beche in respect of Cornwall and he devoted a large amount of time and energy to the study of Cornish rock structures and ore deposits. It appears that he actually covered much of the land himself especially the coastal areas. His important Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset was published in 1839 and his maps although subsequently updated illustrate the diligence of his work.

It should be noted here that the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall had been founded in 1814 and is now the second oldest geological society in the world after the Geological Society of London. Transactions of the society began in 1818 with the first article entitled ‘Formation of Sandstone, occurring in various Parts of the Northern Coasts of Cornwall’. This society remains an important Cornish institution to this day and can be followed online.

The main ore of copper is chalcopyrite and tin cassiterite and found in Cornwall’s igneous rocks, which includes granite. It is the type of rock in which gold is also found and although rare in Cornwall it was extracted from an early age. Proved by analysis of the metals in the Bronze Age Nebra sky disc, dated to before 1600BCE, this artefact also includes Cornish tin in the bronze. The early discovery of copper in Cornwall and Wales during the Copper Age followed by tin from Cornwall helped lead in the better known and more important Bronze Age period. Mining and trading of these Cornish metals created great wealth for many over the centuries especially during Cornwall’s industrial mining period from the early 18th century. Sadly, the heyday of Cornish mining, where some areas of Cornwall were named the most valuable in the world, did not benefit many ordinary Cornish workers.

During the 18th century the discovery of kaolin deposits in 1745 at Tregonning Hill, near Germoe by William Cookworthy would result in the development of the china clay industry. This was an important discovery that Cornwall still benefits from today, taking over from the copper and tin mining as that declined in the 19th century. The degrading and alteration to the moorland granites as they cooled some 280 million years ago created this fine powder mixed in with the other particles. Extraction of the kaolin creates about five parts waste for every part of china clay. Hence we now have what is popularly known as the Cornish Alps and many exhausted clay pits across mid-Cornwall.

Even the huge pits in the ground left from the extraction of china clay have benefited Cornwall. Would Cornwall have the Eden Project where the Carvear China Clay Works existed from the 19th century until exhausted? This has become a major tourist attraction and added to the Cornish economy. Other exhausted pits are aiding Cornwall with its current water supply crisis. The main reservoir on Bodmin Moor, Colliford, currently holds just 60% of its full capacity of 28,540 million litres. This reservoir services 255,000 households in Cornwall and is well below the 80% this time last year and over 95% in 1995 an acknowledged dry year. This is most concerning and in this case not necessarily the fault of South West Water who have made attempts to increase storage capacity. South West Water have taken advantage of exhausted pits for the creation of water storage reservoirs. In 2006 Park Lake was created followed in 2008 by Stannon Lake. These hold 840 and 2,183 million litres respectively and the lake formed at Hawks Tor now allows under drought conditions abstraction of eight million litres of water per day to top up Colliford. Cornwall’s industrial past through its geological makeup and industry is benefitting residents today as well as the tourist industry.

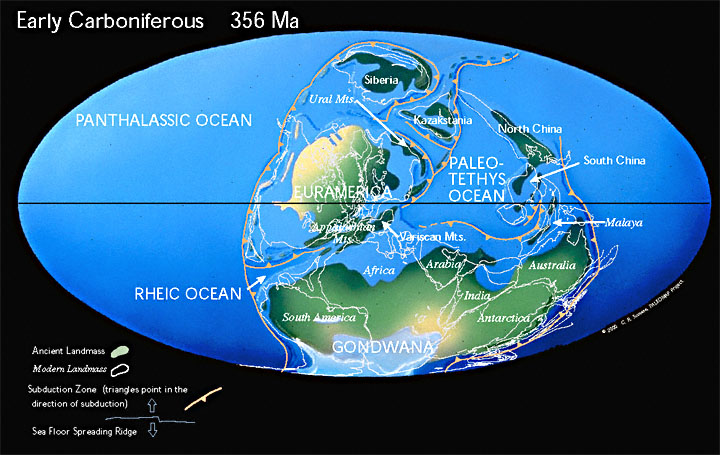

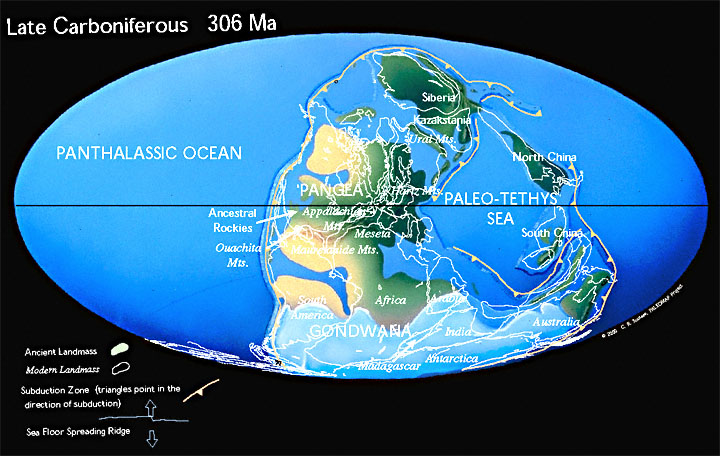

Cornwall has not always been located on earth where it is today, England and Wales moving from a position below the equator and submerged just off the super continent of Gondwana some 400 million years ago. Those in favour of Scottish independent might be pleased to know that Scotland was separated from the rest of the United Kingdom at that time. By 350 million years ago the land had emerged and in a southern desert zone where the laying down of sediments of old red sandstone took place, this is known as the Devonian period. By 280 million years ago Gondwana had joined with the northerly landmass known as Laurasia forming the extra super continent Pangea with the land that would become Cornwall situated around the equator. A period known as the Hercynian orogenic belt evolved which came about through the movement of tectonic plates leading to collision and parts of the original seafloor rising to the surface. This is the period that saw the igneous and metamorphic rocks and minerals that Cornwall would later benefit from being created. Cornwall along with England would gradually move over the following millions of years and join with Scotland forming the British or as increasingly popularly known, the Anglo-Celtic Isles of western Europe. Much more would happen to create the geological landscape of Cornwall during these later millions of years as well as the effects of the various Ice Ages.

A Cornish rock often overlooked today is serpentine, a metamorphic rock often called Cornish marble and found uniquely in multicolours at the Lizard peninsula. It is not found anywhere else like this anywhere else in Britain although there are some less varied deposits elsewhere. This stone is mostly seen today in ornaments found in Cornish homes, those of tourists who have visited the Lizard and collectors of antique serpentine. Although still produced today as small ornamental pieces, serpentines day in the sun as an alternative to marble in buildings was relatively short. For probably centuries serpentine would have been used as stone for building local cottages. An expansion of this took place from 1828 when factories making larger ornaments and household features were established in Penzance.

In 1846 Prince Albert consort to Queen Victoria brought serpentine to greater public notice. On their tour Albert had visited a serpentine works and seen examples of what was being produced, he was most impressed and purchased some pieces. They later went on to purchase more items for their Osborne House home on the Isle of Wight, leading in turn to many of their circle and other wealthy folk purchasing pieces for their own grand homes. The 1851 Great Exhibition saw a further increase in popularity due to the estimated six million visitors and the exhibition of Cornish serpentine. The Lizard Serpentine Company was founded in 1853 and vast quantities of serpentine objects were produced including veneers for many buildings. However, the veneering of buildings was not successful due to lack of resilience to frost and cold weather in other parts of Britain, as opposed to the mild climate of the Lizard peninsula. Large scale production was closed down by the early 1890’s leaving just the small ornamental businesses that we see today.

Space here does not allow other Cornish stones including those created through sedimentary rock formation to be looked at. Slate quarrying and of course the famous Delabole slate production industry has also seen huge activity over the past thousand years. The wide range of rocks and minerals found in Cornwall have shaped the Cornish economy, landscape and its people over the past centuries and will continue to do so far into the future.

![Ertach Kernow - 12.04.2023 [1] Cornwall’s geological legacy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Ertach-Kernow-12.04.2023-1-254x300.jpg)

![Ertach Kernow - 12.04.2023 [2] Cornwall’s geological legacy](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Ertach-Kernow-12.04.2023-2-254x300.jpg)

![[146] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 12 April 2023 - Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 12 April 2023](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/146-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-12-April-2023--300x292.jpg)