Cornwall’s fishing heritage

Cornwall’s fishing heritage is a topic many are interested in and they would have likely seen and enjoyed the BBC documentary film series Cornwall: This Fishing Life. There will be a new series coming out in the New Year and this past week I had the opportunity to sit and chat with the Producer. Realisation that probably far fewer of Cornwall’s residents today know much about Cornish fishing history has produced this somewhat brief overview of a huge subject.

Along with tin mining and production, fishing has been Cornwall’s most profitable and productive historical industry. In the 13th century during the reign of King John a Cornish poet known as Michael of Cornwall wrote about Cornwall’s riches through tin and fish, this wealth however did not necessarily filter down to the ordinary folk. The fish that Cornwall was best known for since earliest times was the pilchard. Since Neolithic times and the last major inundation of the coastline people have settled around the coast and lived off fish and shellfish. Remains of coastal communities have been found all around Cornwall and many of the existing towns and villages around Cornwall’s coast were founded on fishing. Many have moved on to tourism and the like, but fishing still contributes to their economies today.

Prior to the Norman conquest there was little salt available for salting to preserve a catch and the main way of preserving would have been through sun drying. King John granted certain licences to French merchants to allow fishing for a variety of fish, this improved trade and enabled the import of French salt for curing. From this point there was a marked increase of growth in fishing that reached national importance, especially in Cornwall, during the 16th century.

Medieval church records show that there were harbours of some type at Newlyn in 1435 and at Tewynplustri, now Newquay, in 1439. Fishermen in both communities had requested help from Edmund Lacy Bishop of Exeter to carry out repairs to quay’s and jetties.

By Tudor times fishing was so important to the economy of not just Cornwall, but England that the Elizabethan Council of State laid down many regulations from 1588. They had two objectives, to encourage development of the industry and to prevent the pilchards being exported, to serve as food for the people. It even encouraged the eating of fish by having national fast days when eating meat was forbidden. Laws and bylaws were laid down restricting fishing on Sunday’s, the use of drift nets to benefit seine net use and prevention of salting pilchards to prevent export. Within Cornwall and Devon, the herring was fished much more than in many English counties and helped support the pilchard fishing industry. There was a sizeable Cornish sea going population of over 2000 in the late 16th century and it was very profitable for those investing and running fishing businesses. Richard Carew wrote in 1602 in his Survey of Cornwall “But the least fish in bigness, greatest for gain and largest in number is the pilchard”.

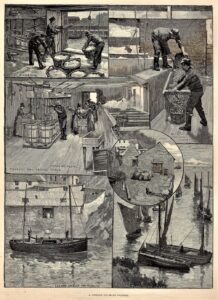

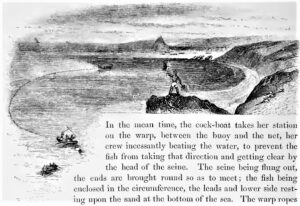

Pilchards started their migration down Britain’s west coast as early as July reaching greater numbers from late August to October. This was a time of great anticipation leading to either a lean winter or one of plenty. There were two methods of catching the Pilchards by drift nets, droving as it was once called, or by use of a seine net. The drift net would be thrown into the path of the shoal and many would entangle and be caught, then be removed and the process repeated. Alternatively, the seine net which they would shoot out around as much of the shoal as the net would allow, up to around 1500 yards, guided by onshore huer’s signalling and bringing it full close to shore. The captured fish would then be emptied out by the smaller boats and taken back to the fish cellars, also known as fish palaces for processing. Droving was looked down on and would have been used by poorer fishermen, who couldn’t afford to buy into a seine. This broke up the shoal and prevented so many fish being caught, hence bylaws restricting this in many places.

Following the pilchard fishing season would be herring fishing and this was carried out by using drift nets. Less well known but important from early times the success of the herring season was mentioned in correspondence dated 1688. This season of fishing followed on from the pilchard fishing season and ran from towards the end of October until December. This was carried out further out to sea and although good quantities were caught it was not in the same league as the pilchard’s numbers caught by the seine nets closer to shore.

Mackerel fishing was also carried out in Cornwall and was said to have been introduced by Breton fishermen. Due to religious persecution in France following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 many Breton Huguenots come to Cornwall, where they would have been able to understand Cornish due to close language connections. Caught using drift nets, but different from those used for pilchard and herring fishing. As well as the nets, boats often differed in design depending on the type of fishing carried out.

Towards the end of the 19th century pilchards no longer came to Cornwall in large numbers, although herring fishing carried on into the early 20th century before gradually stopping. There has been much speculation as to why the pilchards no longer came to Cornwall in such great numbers. A number of surveys were carried out from the late 1940’s, many now consider that it was climate change that stopped the plankton that the European Pilchard feed on coming so close to Cornwall’s coastal waters. However, all is not lost and since the 1990’s there has been a resurgence in Cornish pilchard fishing. Remarketed as Cornish Sardines these are caught by use of modern techniques, based on the historic seine netting. In 2016 over 5000 tonnes were caught by the Cornish ring net fleet that year.

Cornish fishermen have diversified and now shellfish such as brown crab and lobster make up a sizeable quantity of catches along with a variety of other fish. Harbours such as Newquay which saw a steep decline in fishing some 100 years ago are now busier than they were during the mid-20th century. We wait with combined interest and concern at what the forthcoming Brexit talks will bring forth for the future of Cornwall’s ancient fishing industry.

![Edmund Lacy - Indulgence - Newlyn [S] Edmund Lacy - Indulgence - Newlyn 1437](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Edmund-Lacy-Indulgances-Newlyn-S-179x300.jpg)