Ertach Kernow - Celia Fiennes goodbye to Cornwall

Celia Fiennes an intrepid lady who in the final years of the 18th century went on a tour of England and in 1698 Cornwall. Celia entered Cornwall by the Cremyll Ferry on the Rame Peninsula, from where we followed her through various towns and parts of Cornwall down to Land’s End and now will trace the final leg of her Cornish journey as she returns to England.

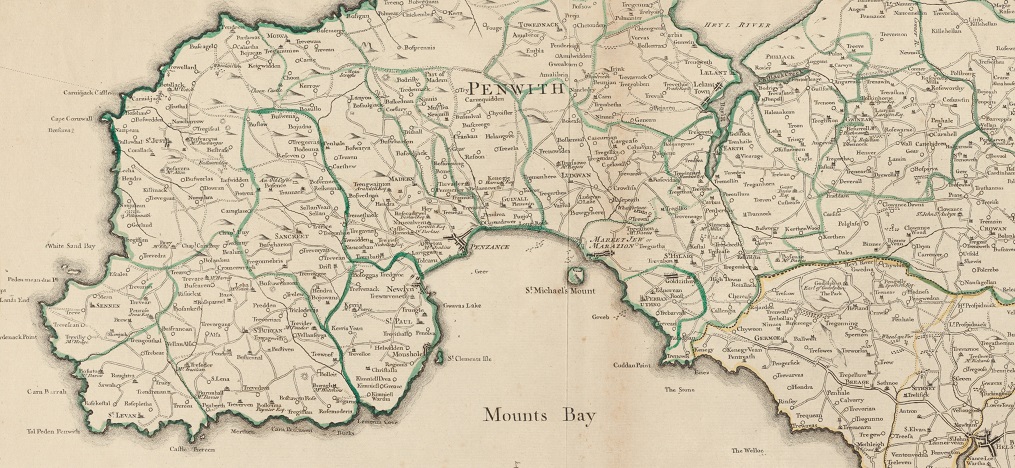

At Land’s End she had observed the Scillies and commented in her diary on the rock formations, later visiting St Just meeting Cornish folk, visiting their homes and complementing their bottled beer. Although she doesn’t make comment about it we can assume that those she met spoke English and that the Cornish language even this far west was now much diminished if not quite at its lowest ebb. Celia returned to Penzance taking in views of Lizard Point and St Michael’s Mount.

As always click the images for larger view

From Penzance arriving in a place named as Hailing Celia mentions ‘Here is abundance of very good Fish tho' they are so ill supply'd at Pensands because they carry it all up ye Country East and Southward. This is an arme of ye North Sea which runs in a greate way into ye Land, its a Large Bay when ye sea comes in and upon ye next hill I ascended from it could discover it more plaine to be a deep water and ye supply of ye maine ocean. Just by here lay some ships and I perceived as I went, there being a Storme, it seemed very tempestious and is a hazardous place in the high tides.’ So, it seems that Penzance was exporting much of its fishing catches to England and perhaps southward refers to the continent. She noted that the Cornish folk also took precautions to protect their roofs due to the storms and extend the life of their thatched roofs. ‘I perceive they are very bleake in these Countryes especially to this North Ocean and ye winds so troublesome they. are forced to spin straw and so make a caul or network to lay over their thatch on their Ricks and out houses, with waites of Stones round to defend ye thatch from being blown away by ye greate winds, not but they have a better way of thatching their Houses with Reeds and so close ye when its well done will last twenty yeares, but what I mention of braces or bands of straw is on their Rickes which only is to hold a yeare.

Regarding harvest farming practices Celia notes the use of smaller horses called Canelles to transport harvest produce. Celia Fiennes had the advantage of seeing it being brought in on the horses backs using a device like a yoke on either side of the horse. The amount was piled so high that it took two people to both lead the horse and support the produce being carried. Celia noted horses weren’t used to pull wagons, which could have carried more, but perhaps this was because the Canelles were the only type of horse available. These were well suited to Cornish farming at that time especially with roads in Cornwall being notoriously poor. She considered the working folk writing ‘I wondred at their Labour in this kind, for the men and the women themselves toiled Like

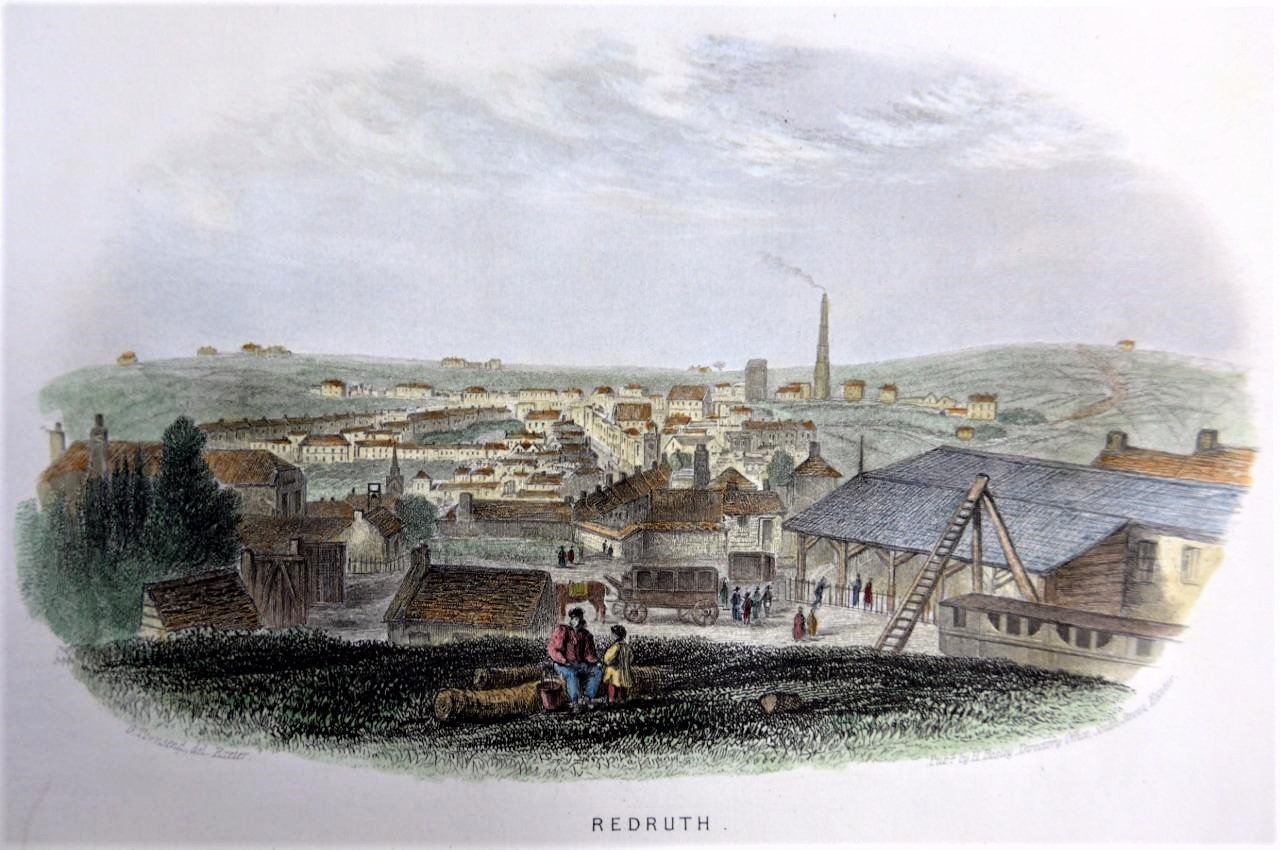

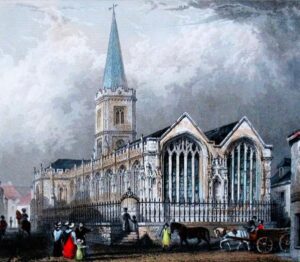

Passing through Redruth, still more of a market and farming community rather than the industrialised mining town it would become a few years later, Celia travelled to Truro. She had passed through Truro previously, but this time stayed longer saying of it ‘a pretty Little town and seaport and formerly was Esteemed the best town in Cornwall, now is the second next Lanstone.’ That it ‘lies down in a bottom, pretty steep ascent as most of the towns in these Countrys, that you would be afraid of tumbling with nose and head foremost Ye town is built of stone — a good pretty Church built all stone and Carv'd on ye outside, it stands in ye middle of ye town, and just by there is a market house on stone pillars and hall on ye top; there is alsoe a pretty good key.’ There still are many older buildings built of stone remaining in Truro, albeit few from Celia’s day, most of the church has been replaced by a cathedral, although St Mary’s aisle part of the original church still exists along with its carvings. The Market House was eventually swept away following the remainder of Middle Row, creating Boscawen Street in the early 19th century. The Quay has been filled and covered following silting of the Truro River and subsequent reduction in trading to become an open public area and used for the popular farmers markets held there. During Celia’s visit it seems Truro was having a low period as she notes that ‘This was formerly a great tradeing town and flourish'd in all things, but now as there is in all places their Rise and period soe this, which is become a Ruinated disregarded place.’ However, as we now know this was a temporary issue and Truro would again rise to become Cornwall’s capital and a city. It seems however that Celia’s most positive thoughts about Truro was as she wrote; I heard a pretty good Sermon but that which was my Greatest pleasure was the good Landlady I had, she was but an ordinary plaine woman but she was understanding in the best things as most, ye Experience of reall religion and her quiet submision and self-Resignation to ye will of God in all things, and especially in ye placeing her in a remoteness to ye best advantages of hearing, and being in such a publick Employment which she desired and aimed at ye discharging soe as to adorne ye Gospel of her Lord and Saviour, and the Care of her Children.’.

Celia Fiennes then writes about Cornwall’s national bird, or as they were described locally as Cornish nightingales, which she could have seen had she stayed with her relatives at Tregony. Would have ‘engaged my stay with them a few dayes or weekes to have given me the diversion of the Country, and to have heard the Cornish nightingales as they Call them, the Cornish Chough, a sort of Jackdaw if I mistake not a Little black bird which makes them a visit about Michaelmas and gives them ye diversion of the notes which is a Rough sort of musick not unlike ye Bird I take them for, so I believe they by way of jest put on the Cornish Gentlemen by Calling them nightingales.’

Two short videos of Cornish Choughs

Celia from Truro made the trip back to St Columb via Mitchell by mostly ‘Lanes and Long miles’. Once again Celia saw no windmills saying, ‘they have only the mills which are overshott and a-Little rivulet of water you may step overturns them, which are the mills for Grinding their Corn and their ore or what Else.’ It’s quite surprising that Celia did not see any windmills as quite a number of them were recorded. Given the number of streams and water flowing throughout Cornwall water mills would have been more common, interesting that she noted these were of the more efficient overshot variety. From St Columb Celia travelled to Wadebridge where her geography went a little awry saying ‘There was a river which was flowed up by ye tyde a Greate way up into the Land, it Came from ye north sea, it was broad, ye bridge had 17 arches.’ The River Camel of course flows into the Celtic Sea not the North Sea, but it should be noted the bridge still had its original seventeen arches, later reduced to thirteen as the riverbanks were extended outwards.

From Wadebridge to Camelford described as a little market town she travelled along lanes lined with banks of great rocks, Cornish stone hedges. She then visits a ‘Large standing water Called Dosenmere poole in a Black moorish Ground and is fed by no rivers except the Little rivulets from some high hills yet seemes allwayes full without Diminution and flows with ye wind and is stored with good ffish.’ Riding to the north Cornish coast Celia saw Lundy formerly owned by her grandfather William Viscount Say and Seale then on to Launceston of which Celia gives a good description.

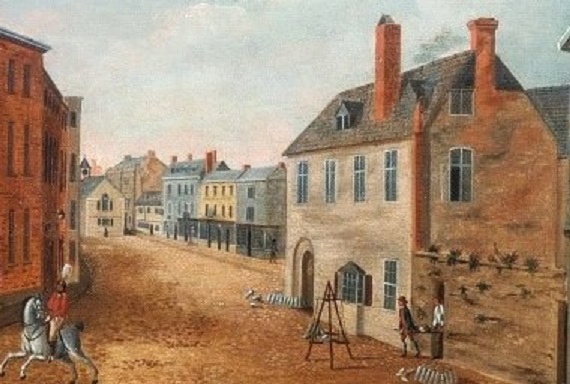

‘There is a Great ascent up into the Castle which Looks very Great and in good repaire the walls and towers round it, its true there is but a part of it remaines, the round tower or fort, being still standing and makes a good appearance. The town is Encompassed with walls and gates, its' pretty Large tho you Cannot discover the whole town, being up and down in so many hills. The streetes themselves are very steep unless it be at the marketplace where is a Long and handsome space set on stone pillars with the town hall on the top, which has a Large Lanthorne or Cupilo in the middle, where hangs a bell for a Clock with a Dyal to the streete. There is in this place 2 or 3 good houses built after the London form by some Lawyers, Else the whole town is old houses of timber work. At a Little distance from the town on a high hill I Looked back and had the full prospect of the whole town which was of a pretty Large extent A mile beyond I crossed on a stone bridge over a river and Entred into Devonshire againe.’

There ends our Cornwall leg of Celia Fiennes tour. Her diary has shown much of Cornwall as it was at the end of the seventeenth century over three hundred years ago and proved a most useful reference to those interested in Cornwall’s history. Many other traveller have had their own tours, but none recorded by a woman during such early times. No doubt Sir Ranulph Fiennes is proud of his distant cousin with her own lust for adventure and exploration.

![Ertach Kernow - Celia Fiennes goodbye to Cornwall [2] Ertach Kernow - Celia Fiennes goodbye to Cornwall](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ertach-Kernow-Celia-Fiennes-goodbye-to-Cornwall-2-259x300.jpg)

![[191] Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 21st February 2024 - Trevor Smitheram, Cornish art and collectables Ertach Kernow Heritage Column - 21st February 2024 - Trevor Smitheram, Cornish art and collectables](https://www.cornwallheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/191-Ertach-Kernow-Heritage-Column-21st-February-2024-Trevor-Smitheram-Cornish-art-and-collectables-282x300.jpg)