Ertach Kernow - Did historic earthworks and borders protect languages?

Were Cornish and Celtic languages protected by physical borders?

The Cornish landscape is covered with historic stone hedges, barrows and many varieties of humps and bumps that may or may not hide ancient artefacts. Sometimes we might stand right above a historic site and see nothing of potentially interesting archaeology lying just a few feet below us. Aerial photography can pick out some remains of stone walls of buildings based on an outline given away by plant growth. Often it is down to newer technology which when employed on a site reveals so much more than even the eye can see.

As always click the images for larger view

We must also thank our Neolithic forefathers for the many standing stones, quoits and with stone circles constructed into the Bronze Age. The vast majority of ancient and historic earthworks that here in Cornwall we see in hillforts, cliff castles and rounds were created during the Bronze and Iron Ages. Later in the Roman and immediate after medieval periods other longer linier earthworks were created. These walls were constructed to act as defensive obstacles the most famous in Britain being Hadrian’s Wall built from 122CE. Twenty years later the Romans later built the further northern Antonine Wall which is far less well-known. The Antonine Wall was not the stone construction of the slightly earlier Hadrian’s Wall but largely turf on a stone base with a deep ditch to the northern side and perhaps topped with a timber palisade. It lies between the Firth of Forth north of Edinburgh and the Firth of Clyde north of Glasgow and was 39 miles long. It was abandoned not long after it was constructed and the troops relocated to the southern Hadrian’s Wall.

The Roman period saw the names of the various tribes inhabiting Britain named by Roman writers such as the Egyptian born Ptolemy. Unlike the continental tribes which these writers named as Celts or Gallia, those in Britain were referred to as Britons. The language spoken throughout Britain at that time is now known as Common Brythonic the forerunner of the modern Brythonic languages of Wales, Cornwall and Brittany. Although now extinct the language of what we know as Scotland or Pictland is believed to have originally been a Brythonic language. With the separation by the Roman Hadrian’s Wall this may have led to Brythonic ‘Pictish’ evolving independently. It is likely there would have been strong regional or tribal differences in pronunciation as we see even today across Britain with the English language. Invasion by the Gaels from Ireland later known as the Scotti saw the Pictish Brythonic language subsumed and lost

To the southwest of Britain Ptolomy names the tribe inhabiting modern Cornwall, Devon and West-Somerset the Damnonii. The Roman capital for this area was Isca Dumnoniorum, modern day Exeter. It is highly unlikely that all the early Britons in this region formed a single tribe and this was purely an administrative area formed and named by the Romans. There would have been many smaller tribes making up this area under individual chieftains and speculatively it was Roman rule that later led to some form of unification, especially in Cornwall, with a tribal or regional king. Cornwall has a large number of hillforts built in the Bronze and Iron Ages and with evidence of countless small and fortified farmsteads known as ‘rounds’ existing. Lack of any evidence of central control by a Briton ruler such as coins points to a fractured tribal and independent groupings of people under the Roman administrative banner of Dumnonia.

Recent evidence proves that the Romans did come into Cornwall and build forts. However, there is no evidence of fighting leading to the assumption that perhaps the small Cornish tribes were more interested in trading, especially tin, with the Romans. Cornish people had been trading with other continental cultures for many centuries as a growing catalogue of recent evidence proves. There seems to have been greater trading interaction between what would later become Cornwall and northern France, then known as Gaul, in the region known later as Amorica and todays Brittany. Following Julius Ceasars invasion of Gaul, in Latin Gallia, the Romans had divided it into five units of which Gallia Celtica was the largest. The conquest of Gaul was complete by 52BCE with the defeat of the heroic Celtic leader Vercingetorix. So by the time the Romans had taken control of Britain by 87CE trading between Cornwall and Roman controlled Brittany would have been commonplace and quite normal for the Cornish tribal tin traders.

Following the withdrawal of the Romans around 410CE early medieval Britain became hotchpotch of competing tribes gradually becoming larger kingdoms during the Anglo-Saxon period. One large earthwork was completed during the early-medieval period by a ruler of Mercia after which it is named, Offa’s Dyke. This runs approximate 150 miles along the border between England and Wales today but is believed to have been begun in the 5th century and then extended by Offa during the second half of the 8th century. There is also the far lesser-known Wats Dyke a smaller and less well-preserved dyke to the north of Offa’s running for 40 miles, often parallel to it. Much less is known about Wat’s Dyke and it’s believed to have perhaps preceded Offa’s

Although there are these walls and earthworks that separated what would become England from the early Scottish and Welsh nations there is nothing separating England from Cornwall. In 936CE King Æthalstan threw the Cornish out of Exeter and banished them to the west of the River Tamar setting the eastern bank as the border between Cornwall and England. This natural border which stretched to within just four miles of the north coast was quite sufficient to delineate Cornwall from England. These barriers sufficed for centuries as a marker and within these the Celtic languages survived until the gradual supremacy of England saw their decline.

There are limited records in the Welsh Chronicles of Cornwall being a separate kingdom with kings, such as King Dungarth who is commemorated in ‘King Doniert’s Stone’. The likelihood is that there were many smaller tribal chieftains vying for power within a loosely knit kingdom under a nominal national king or warlord. We do have some other interesting earthworks remaining in Cornwall which are often overlooked by those outside their immediate areas. These are thought to have been constructed during the early medieval period.

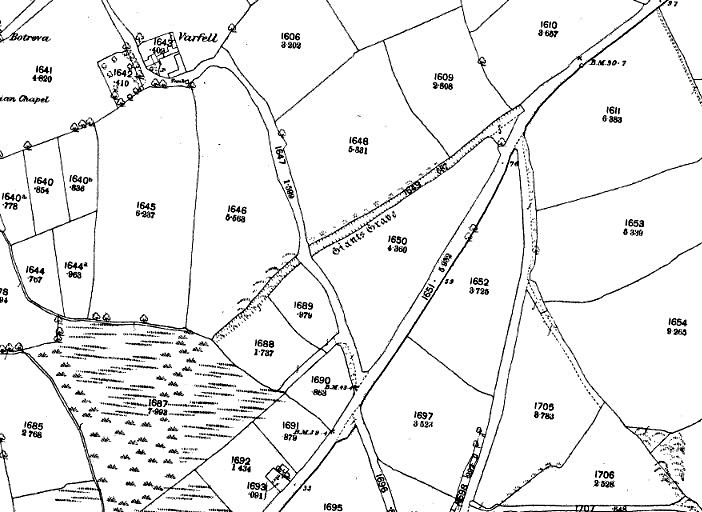

In the far west of Cornwall there is an earthwork called the ‘Giant’s Grave’ near the hamlet of Varfell. This linier earthwork is a mere 350 metres long and it is thought that much of what may have been part of this historic work has been destroyed through road construction. Speculatively it has been suggested that it may have stretched across the whole of the Penwith peninsula at its narrowest point creating a western defensive area to Land’s End.

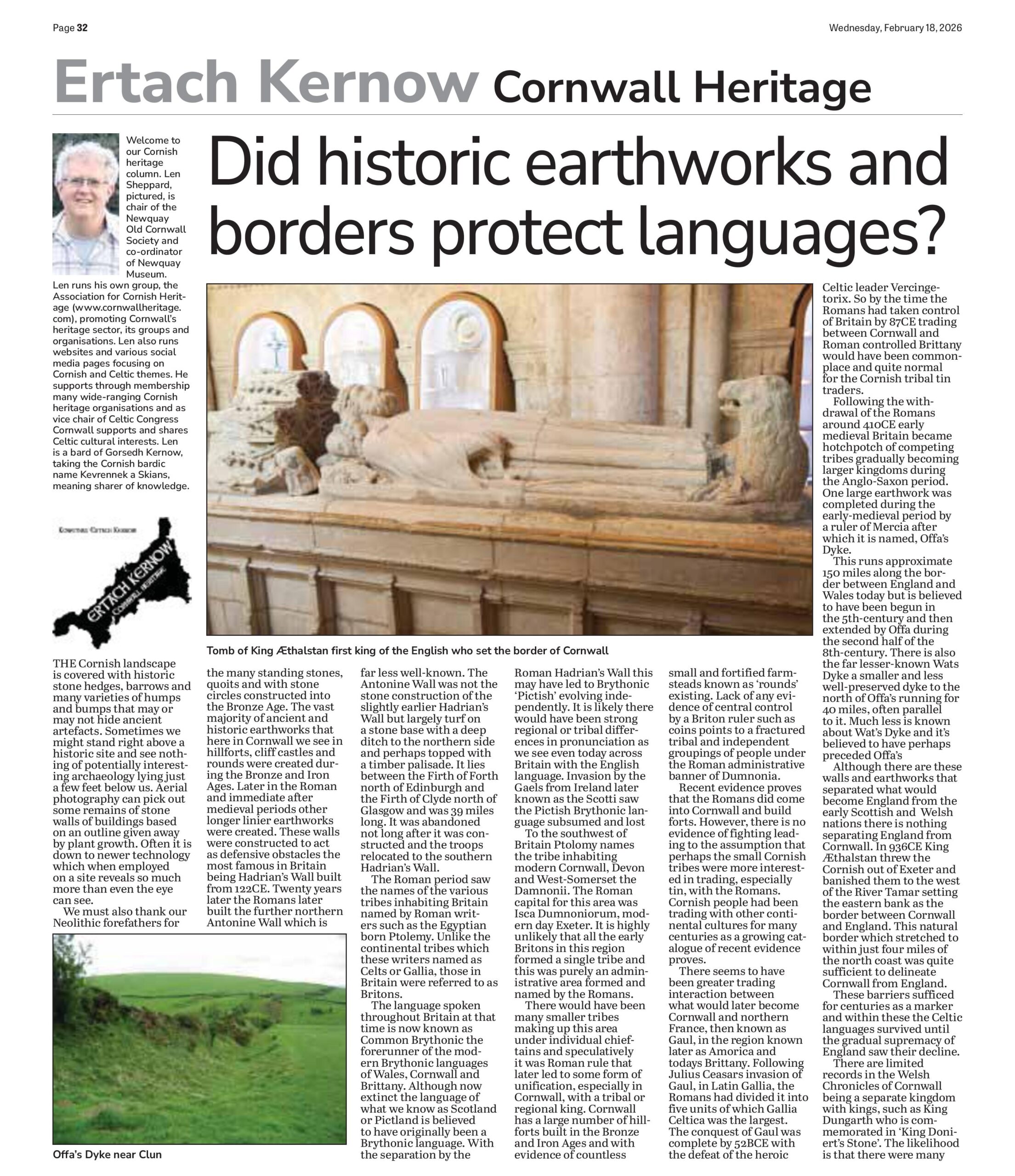

At St Agnes there is the ‘Bolster Bank’ of which some thousand metres still survives. This is about three metres high from ditch bottom to top. Originally this would have been greater if allowing for erosion and filling of the ditch. It originally ran from Chapel Coombe in the southwest to Trevaunance Coombe in the northeast cutting off the area of land dominated by St Agnes Beacon, with just the central section still remaining.

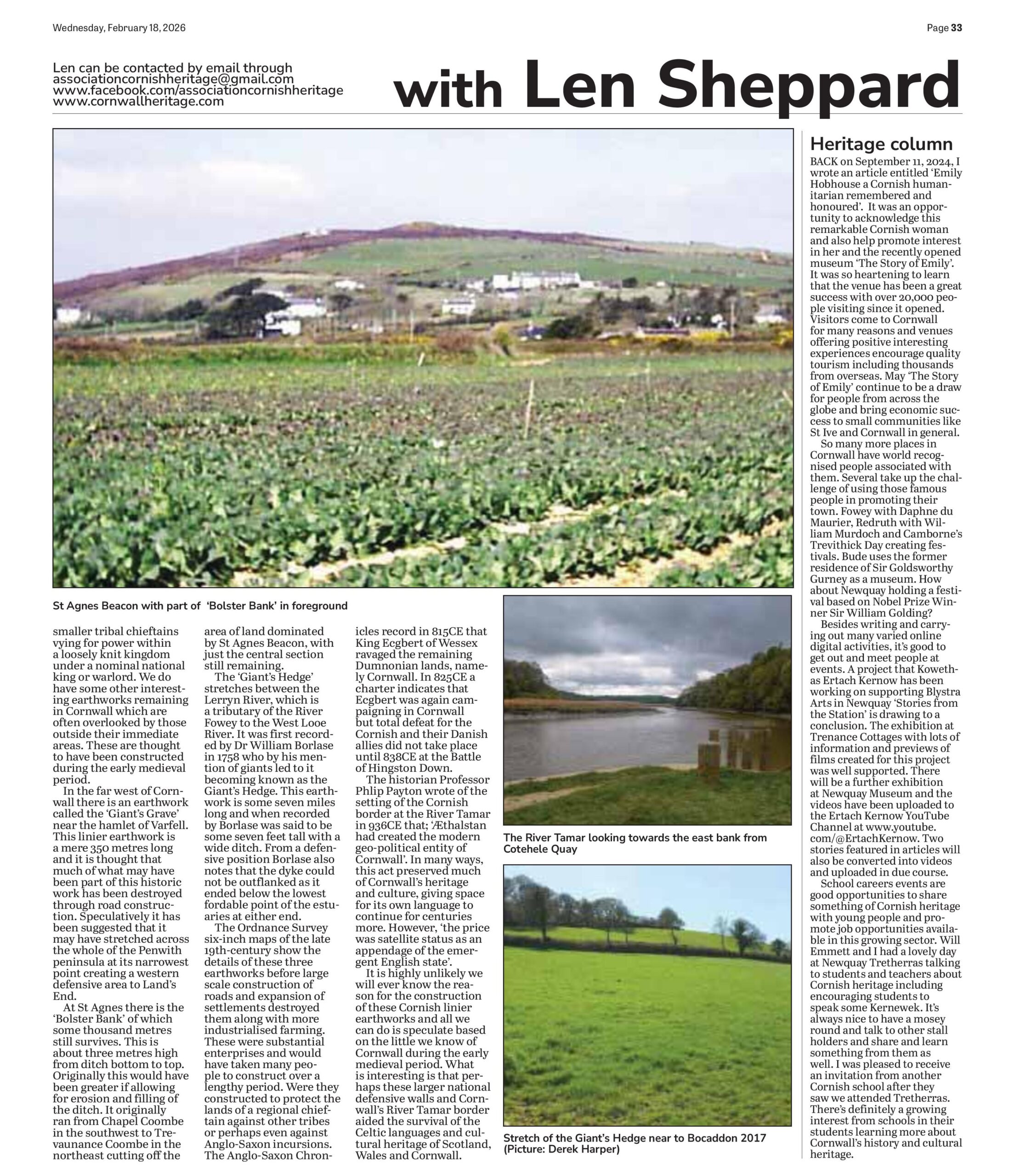

The ‘Giant’s Hedge’ stretches between the Lerryn River, which is a tributary of the River Fowey to the West Looe River. It was first recorded by Dr William Borlase in 1758 who by his mention of giants led to it becoming known as the Giant’s Hedge. This earthwork is some seven miles long and when recorded by Borlase was said to be some seven feet tall with a wide ditch. From a defensive position Borlase also notes that the dyke could not be outflanked as it ended below the lowest fordable point of the estuaries at either end.

The Ordnance Survey 6-inch maps of the late 19th century show the details of these three earthworks before large scale construction of roads and expansion of settlements destroyed them along with more industrialised farming. These were substantial enterprises and would have taken many people to construct over a lengthy period. Were they constructed to protect the lands of a regional chieftain against other tribes or perhaps even against Anglo-Saxon incursions. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles record in 815CE that King Ecgbert of Wessex ravaged the remaining Dumnonian lands, namely Cornwall. In 825CE a charter indicates that Ecgbert was again campaigning in Cornwall but total defeat for the Cornish and their Danish allies did not take place until 838CE at the Battle of Hingston Down.

The historian Professor Philip Payton wrote of the setting of the Cornish border at the River Tamar in 936CE that; ‘Æthalstan had created the modern geo-political entity of Cornwall’. In many ways, this act preserved much of Cornwall’s heritage and culture, giving space for its own language to continue for centuries more. However, ‘the price was satellite status as an appendage of the emergent English state’.

It is highly unlikely we will ever know the reason for the construction of these Cornish linier earthworks and all we can do is speculate based on the little we know of Cornwall during the early medieval period. What is interesting is that perhaps these larger national defensive walls and Cornwall’s River Tamar border aided the survival of the Celtic languages and cultural heritage of Scotland, Wales and Cornwall.