Ertach Kernow - Coastal erosion endangers buildings and heritage

Cornish sea views from your lounge window is something that many people dream about. The problem is that you may end up far nearer the sea than originally planned with your lounge lying in tatters on the beach. Of course this is about coastal erosion and Cornwall’s tall imposing cliffs and beaches are constantly under attack. Besides the recent devastating damage caused by Storm Goretti to trees and communities there would have been some additional coastal erosion, the results perhaps yet to be seen. Storms, depending on direction cause many alterations to our coastline including cliff falls and large movement of sand.

As always click the images for larger view

Sometimes the removal of sand has a temporary interesting effect by uncovering what lies beneath. This may be long lost shipwrecks, or in many places around the coast submarine forests of trees submerged by a rising tide eons ago. The most famous here in Cornwall is that at Mount’s Bay which is uncovered from time to time and visible at very low tides and sometimes following a storm. Estimated to date from some 4,000 years ago it perhaps indicated when St Michael’s Mount became a tidal island. The name for the mount in Kernewek is ‘Karrek Loos yn Koos’, meaning ‘Grey Rock in the Wood', indicating existence of the forest was known to people many centuries ago. The first recording of this was mentioned by travelling antiquarian John Leland in the 16th century.

Highly publicised was the movement of sand and erosion of sand dunes at Crantock during storms of 2023, which caused unstable cliffs of sand metres high. Where these exist they are a danger to the public as they could collapse at any point burying anybody too close, a substantial distance should be maintained. Many people think of Cornwall as mainly granite, this is far from the case. Yes, inland around Bodmin Moor and other areas there are vast areas dominated by granite beneath the surface soil. The coastal cliffs are often not anywhere near as substantially strong as people might believe. In many places they are layered sedimentary rock and very susceptible to weathering and undermining by the sea.

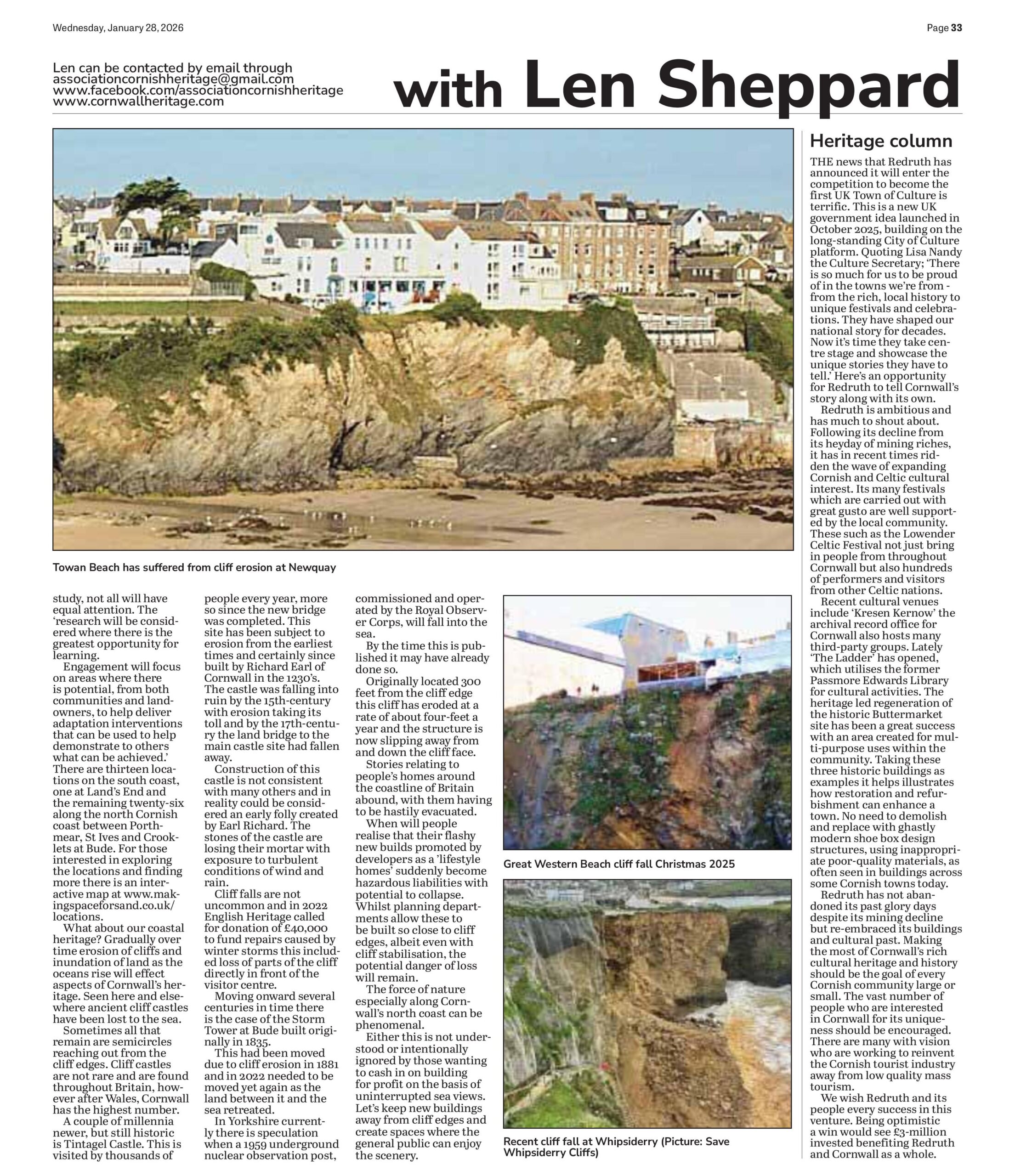

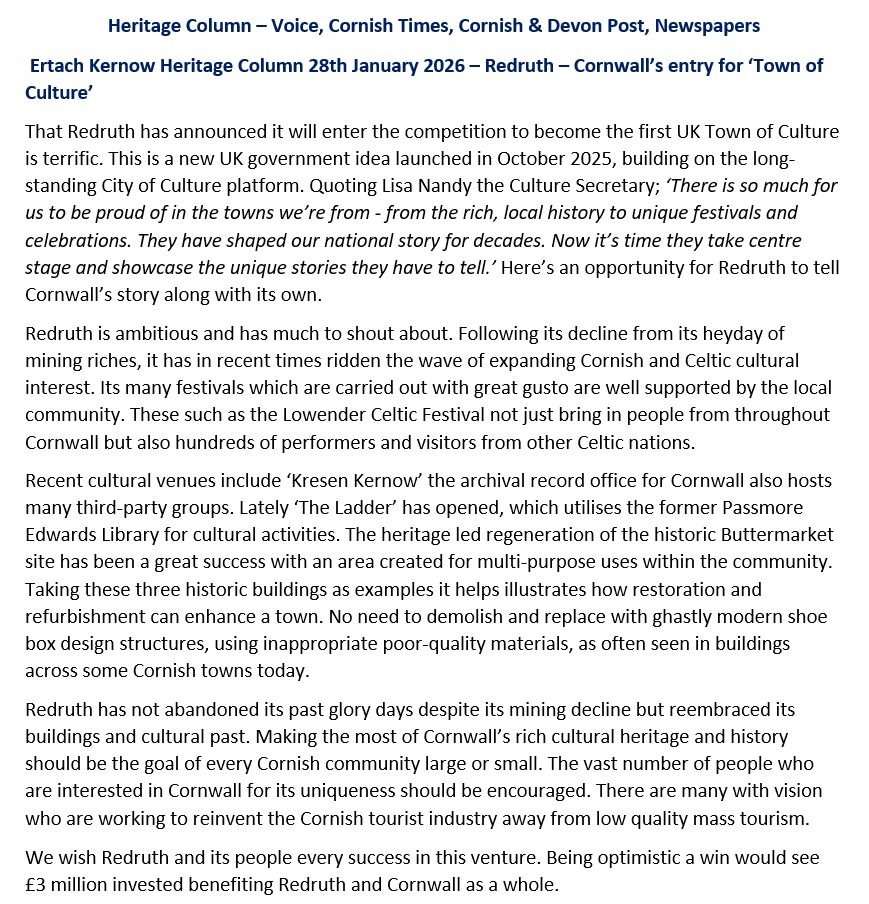

Taking the Newquay area as an example, the cliffs here have seen substantial rockfalls over the past few years. From Watergate Bay through to Whipsiderry, Tolcarne, Great Western and Towan Beaches, all these have experienced erosion with numerous attempts to stabilise the cliff faces. Where this has been done it usually includes drilling into the rock face and inserting large metal rods and meshing, perhaps also including drainage pipes to alleviate water pressure. This is often done when there is a commercial reason to do it, such as building high value properties close to the cliff edge. Examples of this include below the former Trebarwith Hotel, between Newquay’s Great Western and Towan beaches, where new properties have been built. An ongoing battle is currently taking place at Whipsiderry where a number of substantial cliff falls and legal battles have so far prevented the construction of seven cliff edge properties. The latest fall took place adjacent to where cliff stabilisation had already taken place. Who can guarantee that this has not destabilised the nearby existing work? Furthermore, who in their right mind would purchase one of the planned ‘luxury villas’, each costing £1 million, with such potential danger even with cliff stabilisation.

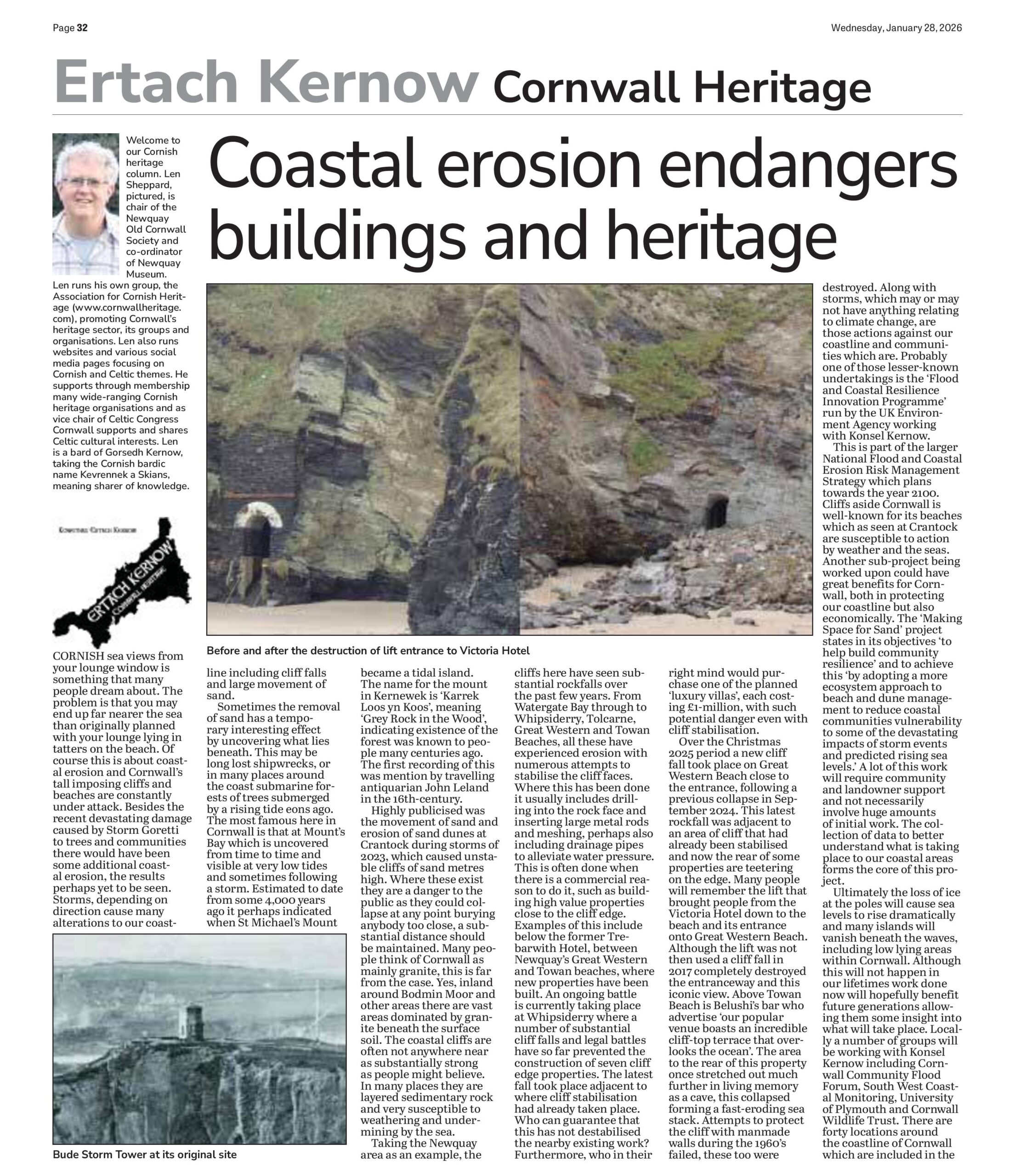

Over the Christmas 2025 period a new cliff fall took place on Great Western Beach close to the entrance, following a previous collapse in September 2024. This latest rockfall was adjacent to an area of cliff that had already been stabilised and now the rear of some properties are teetering on the edge. Many people will remember the lift that brought people from the Victoria Hotel down to the beach and its entrance onto Great Western Beach. Although the lift was not then used a cliff fall in 2017 completely destroyed the entranceway and this iconic view. Above Towan Beach is Belushi’s bar who advertise ‘our popular venue boasts an incredible cliff-top terrace that overlooks the ocean’. The area to the rear of this property once stretched out much further in living memory as a cave, this collapsed forming a fast-eroding sea stack. Attempts to protect the cliff with manmade walls during the 1960’s failed, these too were destroyed.

Along with storms, which may or may not have anything relating to climate change, are those actions against our coastline and communities which are. Probably one of those lesser-known undertakings is the ‘Flood and Coastal Resilience Innovation Programme’ run by the UK Environment Agency working with Konsel Kernow. This is part of the larger National Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy which plans towards the year 2100.

Cliffs aside Cornwall is well-known for its beaches which as seen at Crantock are susceptible to action by weather and the seas. Another sub-project being worked upon could have great benefits for Cornwall, both in protecting our coastline but also economically. The ‘Making Space for Sand’ project states in its objectives ‘to help build community resilience’ and to achieve this ‘by adopting a more ecosystem approach to beach and dune management to reduce coastal communities vulnerability to some of the devastating impacts of storm events and predicted rising sea levels.’ A lot of this work will require community and landowner support and not necessarily involve huge amounts of initial work. The collection of data to better understand what is taking place to our coastal areas forms the core of this project.

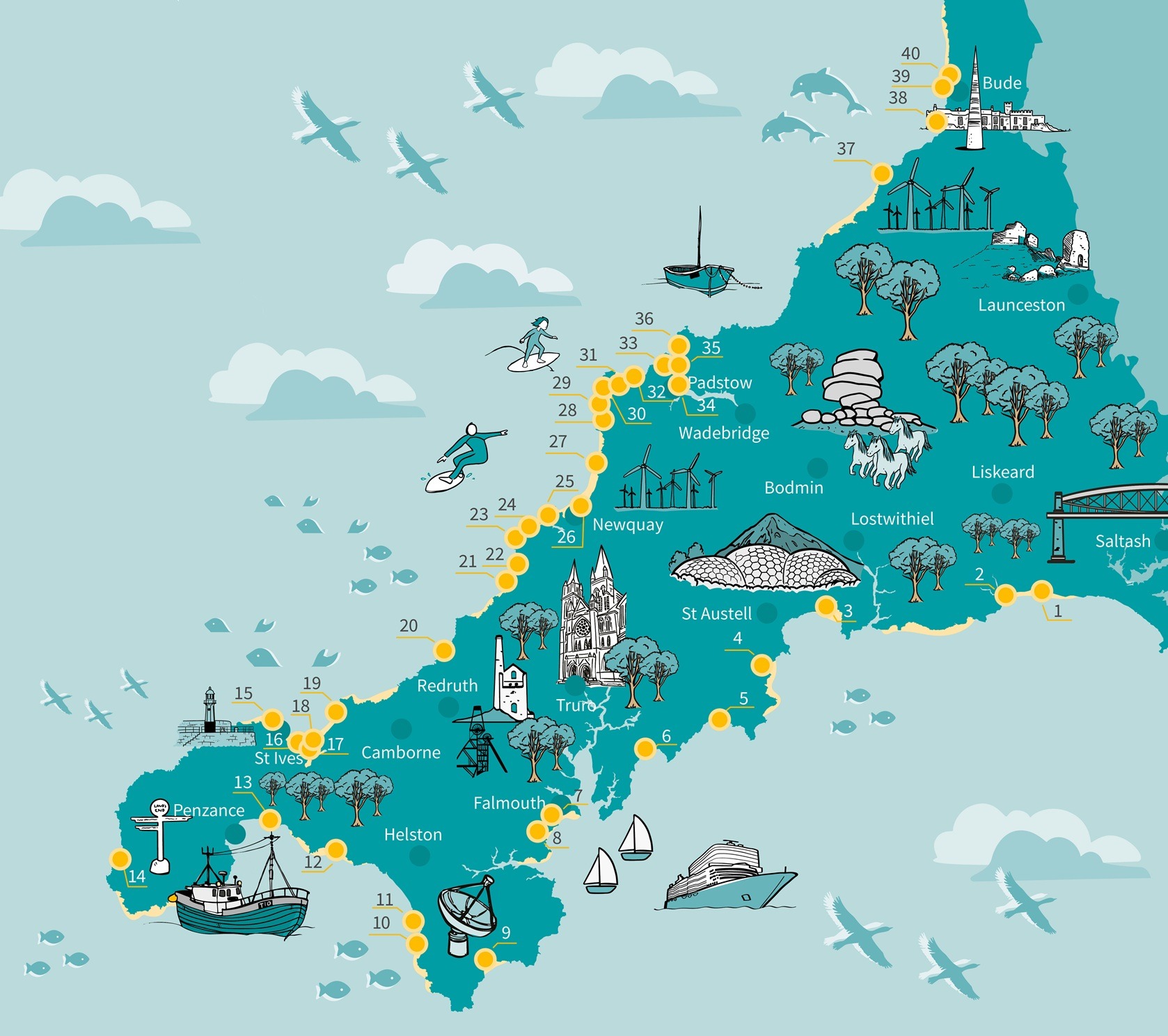

Ultimately the loss of ice at the poles will cause sea levels to rise dramatically and many islands will vanish beneath the waves, including low lying areas within Cornwall. Although this will not happen in our lifetimes work done now will hopefully benefit future generations allowing them some insight into what will take place. Locally a number of groups will be working with Konsel Kernow including Cornwall Community Flood Forum, South West Coastal Monitoring, University of Plymouth and Cornwall Wildlife Trust. There are forty locations around the coastline of Cornwall which are included in the study, not all will have equal attention. The ‘Research will be considered where there is the greatest opportunity for learning. Engagement will focus on areas where there is potential, from both communities and landowners, to help deliver adaptation interventions that can be used to help demonstrate to others what can be achieved.’ There are thirteen locations on the south coast, one at Land’s End and the remaining twenty-six along the north Cornish coast between Porthmear, St Ives and Crooklets at Bude. For those interested in exploring the locations and finding more there is an interactive map at www.makingspaceforsand.co.uk/locations.

What about our coastal heritage? Gradually over time erosion of cliffs and inundation of land as the oceans rise will effect aspects of Cornwall’s heritage. Seen here and elsewhere ancient cliff castles have been lost to the sea. Sometimes all that remain are semicircles reaching out from the cliff edges. Cliff castles are not rare and are found throughout Britain, however after Wales, Cornwall has the highest number.

A couple of millennia newer, but still historic is Tintagel Castle. This is visited by thousands of people every year, more so since the new bridge was completed. This site has been subject to erosion from the earliest times and certainly since built by Richard Earl of Cornwall in the 1230’s. The castle was falling into ruin by the 15th century with erosion taking its toll and by the 17th century the land bridge to the main castle site had fallen away. Construction of this castle is not consistent with many others and in reality could be considered an early folly created by Earl Richard. The stones of the castle are losing their mortar with exposure to turbulent conditions of wind and rain. Cliff falls are not uncommon and in 2022 English Heritage called for donation of £40,000 to fund repairs caused by winter storms this included loss of parts of the cliff directly in front of the visitor centre.

Moving onward several centuries in time there is the case of the Storm Tower at Bude built originally in 1835. This had been moved due to cliff erosion in 1881 and in 2022 needed to be moved yet again as the land between it and the sea retreated.

In Yorkshire currently there is speculation when a 1959 underground nuclear observation post, commissioned and operated by the Royal Observer Corps, will fall into the sea. By the time this is published it may have already done so. Originally located 300 feet from the cliff edge this cliff has eroded at a rate of about four-feet a year and the structure is now slipping away from and down the cliff face. This story was heavily followed on social media with the bunker slipping down to the sea a few days before this article was first published.

Stories relating to people’s homes around the coastline of Britain abound, with them having to be hastily evacuated. When will people realise that their flashy new builds promoted by developers as a ’lifestyle homes’ suddenly become hazardous liabilities with potential to collapse. Whilst planning departments allow these to be built so close to cliff edges, albeit even with cliff stabilisation, the potential danger of loss will remain.

The force of nature especially along Cornwall’s north coast can be phenomenal. Either this is not understood or intentionally ignored by those wanting to cash in on building for profit on the basis of uninterrupted sea views. Let’s keep new buildings away from cliff edges and create spaces where the general public can enjoy the scenery.