Ertach Kernow - 18th Century tour St Michael’s Mount towards St Agnes

Cornwall in the mid-18th century was very different from even just a hundred years later when Cornish mining had reached its peak. This was a time when the Reverend Richard Pocock, a keen observer of people and places and an enthusiastic traveller was touring Cornwall. In earlier articles we have seen the Reverend Pocock observe and visit many places and the earlier incarnations of buildings which we now see as historic. Learning something of their previous structure adds to our own knowledge about these places.

Following on from his visit to Penzance the next obvious choice of places to visit was St Michael’s Mount. He begins by mentioning its name in the Cornish language Caricause in Cous, with the translation given by him as ‘hoary rock in the wood’. Earlier in 1680 it was mentioned as ‘Carrack Looes en Cooes’, today in it would be spelt differently as ‘Karrek Loos yn Koos’ with a similar translation of ‘grey rock in the woodland’. Languages evolve and place names are often changed through mishearing or errors in writing. One can take the horrendous anglicised name change of Cornwall’s highest tor on Bodmin Moor, in Cornish Bronn Wenneli, as an example. One would hope the anglicised name will be officially changed to its original Cornish name in due course. Pocock mentions that St Michael’s Mount is a tidal island and that the remains of trees could be found under the sand, as is the case today when storms scour the sand away.

Interestingly the Reverend Pocock mentions he was accompanied on this visit by the renowned Cornish antiquarian Dr William Borlase. He provides us with a description of the island and size saying it is a mile in circumference and mentions a hanging garden on part of the east side. However, the garden terraces visitors see today weren’t put in place until 1887. It was then that Sir John St Aubyn, later to become the 1st Baron St Leven, had these created. It contains many sub-tropical plants which are protected from frost by the nature of the granite island. The stones of the island it seems absorbs sufficient heat to help keep a temperature suitable for delicate plants to survive. For those interested in seeing the gardens, these are now closed until 1st May later this year to allow time for maintenance.

In earlier times as Dr Pocock learned from William Borlase there were rich veins of tin on the island which were mined. It was then many copper instruments of war, axes, spearheads and swords wrapped in linen were discovered. This shows the Mount had been used as a defensive location since before the Bronze Age, including during the short period of the Copper Age. The discovery of tin and its addition to copper then led to the making of bronze weapons and tools, which heralded in the Bronze Age. Some two-thousand years later the Mount began to take on a religious role when following a vision of St Michael the Archangel in 495CE a chapel dedicated to him was constructed. Some centuries later this was followed by the establishment of a Celtic monastery there. When King Edward the Confessor built a chapel there he handed the Mount to the Benedictine order at Mont St Michel in France. The present church building was begun in 1135 by Abbot Bernard of Mont St Michel and consecrated in 1144, St Michael’s Mount then becoming part of an important pilgrimage route. These religious connections would have been of great interest to the Reverend Pocock. In his text Dr Pocock mentions the ‘mole’ for shipping, a pier likely constructed in 1727 when the harbour facilities were improved. In time this led to the harbour becoming a growing seaport for fishermen and larger vessels. He mentions warehouses and public houses showing the growth of this small settlement was well underway by the mid-18th century.

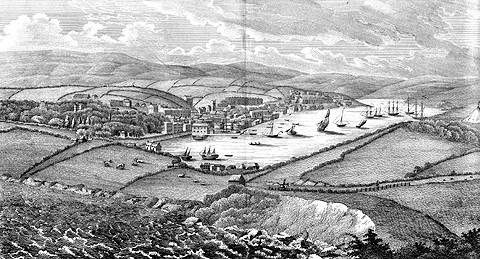

On leaving St Michael’s Mount Dr Pocock headed towards the Lizard and Helston. He notes that he saw many tin works and where the River Hele rises acting as a ‘cut across for communication’. Arriving at Helston, a borough town, Pocock comments of the location as being to the side of a hill with the small river running by it into ‘Loo pool, a large lake made by a neck of land between it and the sea’, he continues ‘below this there are large timber yards and they have shops in the town to supply the neighbouring country.’ Although he doesn’t say it he indicates that Helston was a successful economic settlement. It would as a Stannary town grow in importance as Cornish mining became increasingly industrialised, with improved pumping engines, through the late 18th and into the 19th centuries. What Dr Pocock was seeing was a transition period to greater production and stability in the growth in Cornish mining, excepting a difficult period in the late 1780’s, into the early 19th century.

Travelling to the Lizard Dr Pockock makes some interesting observations about serpentine, the rock we best associate with small ornaments today. This was obviously not being quarried as it would a century later for ornamental purposes and he calls it ‘soapy rock’ alluding to its texture when wet in its natural form. What is interesting is that there was no use for the serpentine but he mentions white patches in the red soapy rock. These once extracted Pocock says were mostly valued for making porcelain in Bristol, with a price of five pounds a ton paid for it. This was a time before the use of Kaolin, discovered by William Cookworthy at Tregonning Hill, and developed by him for use in porcelain manufacture from 1768 and later bone china. What it would appear Dr Pockock was writing about was a fibrous rock Chrysotile Serpentine, also known as white asbestos.

Heading south-east towards Helford a dozen or so barrows were observed along with large stones in a circle covered by heath. This is likely Goonhilly Downs as Pocock mentions ‘near the dry tree’ which is a large menir standing 3 metres tall. The erection of this stone dates from the Bronze Age some 3,500 years ago and would have stood a further metre higher during Dr Pocock’s time, with this length being knocked off during World War One for use in road building. It had been toppled and was later re-erected in 1927 by Porthousestock quarrymen under instruction from Colonel Sir Courtney Vyvyan of Trelowarren. On arriving along the Helford we are told it had a only a dozen houses but fine harbour and quay used primarily for the export of corn.

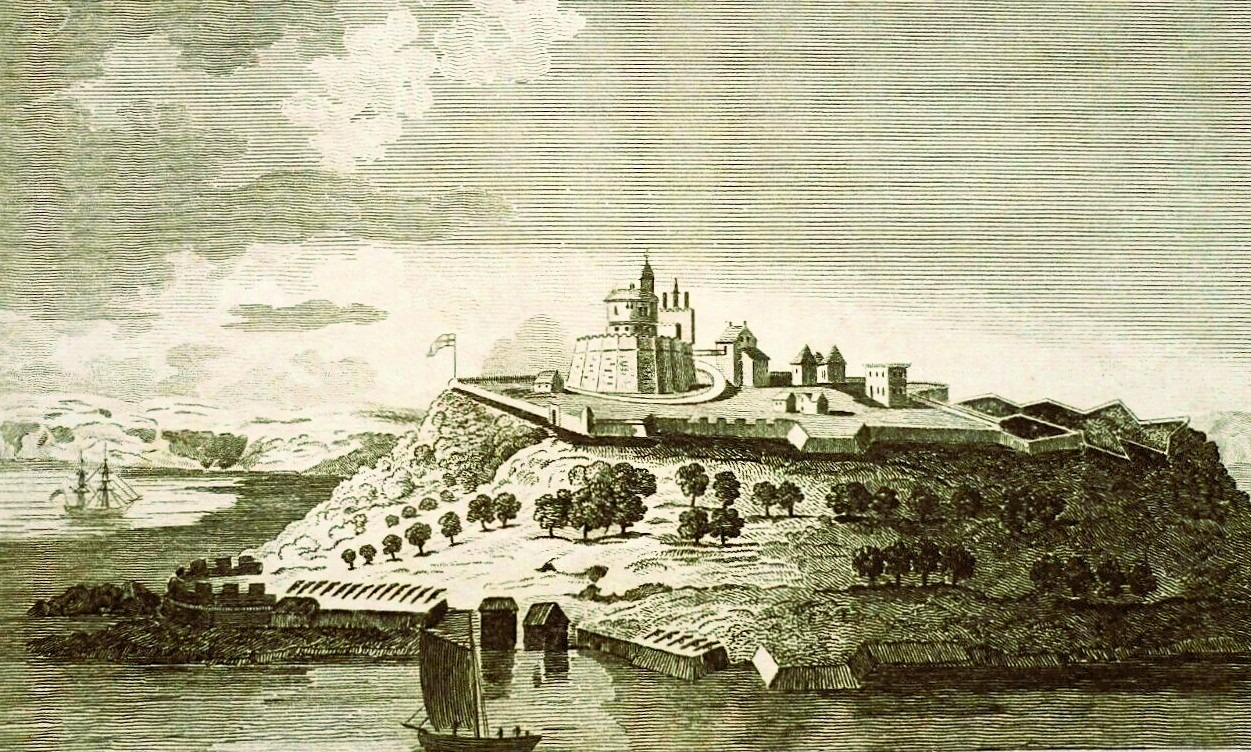

The fortresses of Pendennis Castle, described as very strong and St Mawes as now entirely neglected are attributed to Henry VIII. Mention of the siege of Pendennis and the lines made by the Parliamentary forces during the Civil War are noted along with that a ‘Mr Carteret of the Isle of Jersey sent them frequent supplies.’ This was a George Carteret from a prominent family in Jersey who took to privateering during the civil war against Parliamentry rule. An interesting aside is that following the Restoration in 1660 George Carteret was granted a large tract of land in the American Colonies. This he named New Jersey with his cousin Philip Carteret becoming the first colonial governor. Today New Jersey is one of the most successful and wealthy states within the USA.

Returning to the Reverend Pocock’s tour he then made his way to Penryn commenting that it had similar trades at Falmouth. Through his writing there is no doubt that he took a great interest in mining and the Cornish tin industry, which he describes in great detail. Perhaps something for another article. Once the tin had been smelted it was cast in granite moulds and the stamp of the smelting house with the initials of the person who ‘coyns’ it. The blocks were then transported to one of the mint towns of Lostwithiel, Truro, Helston, Liskeard and Penzance. Here a corner was cut off the block and tested and a mint mark added. Truro was the largest mint town with about 3,170 blocks coined by Dr Pocock’s reckoning. Apparently at this time a quantity was exported to Turkey with the remainder being cast into smaller blocks of between two to seven pounds weight.

blog It was then time to move towards the North Cornish coast and visit St Agnes, where again Dr Pocock was much intrigued by the Cornish tin industry. For those who have missed earlier travels of Dr Pocock these can be found on this website by clicking the links below.