Ertach Kernow - Cornish minerals their past and future uses

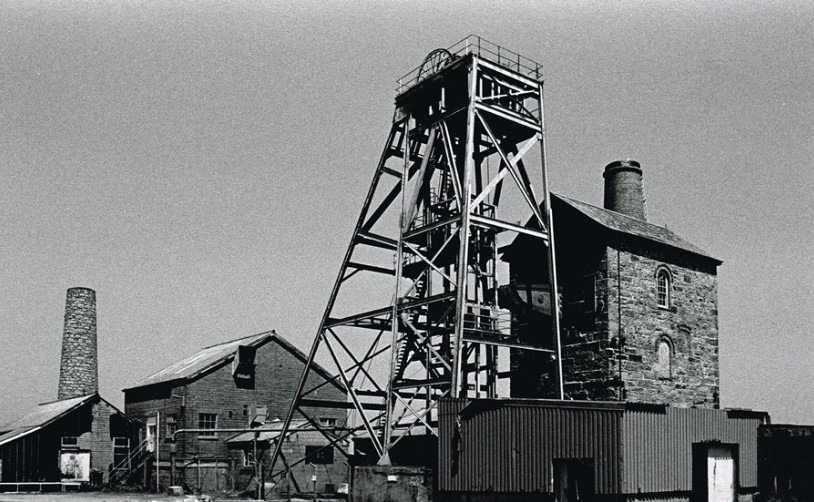

Cornish mining and engineering are amongst the most important parts of Cornwall’s heritage. Although we are reminded of this just about wherever one travels throughout Cornwall perhaps most people no longer think about or take interest in the huge number of Cornish stacks and engine houses.

When talking about Cornish mining most people think about tin, then maybe copper as the driving force behind Cornish mining. With fifteen percent of the world’s minerals types found in Cornwall there has been a lot more interest in many others, even more so today. Some parts of Cornwall have little in the way of tin or copper but had mines dedicated to say lead and silver such as the Lanhenver Mine in Newquay. In fact when looking at some areas of Cornwall for evidence of mining this can be pretty thin on the ground. The vast majority of Cornish mining took place towards the west, especially around Redruth and Camborne. There were also substantial mines around St Just above Land’s End and various clusters around Perranporth, St Austell, Caradon Hill and west of Callington.

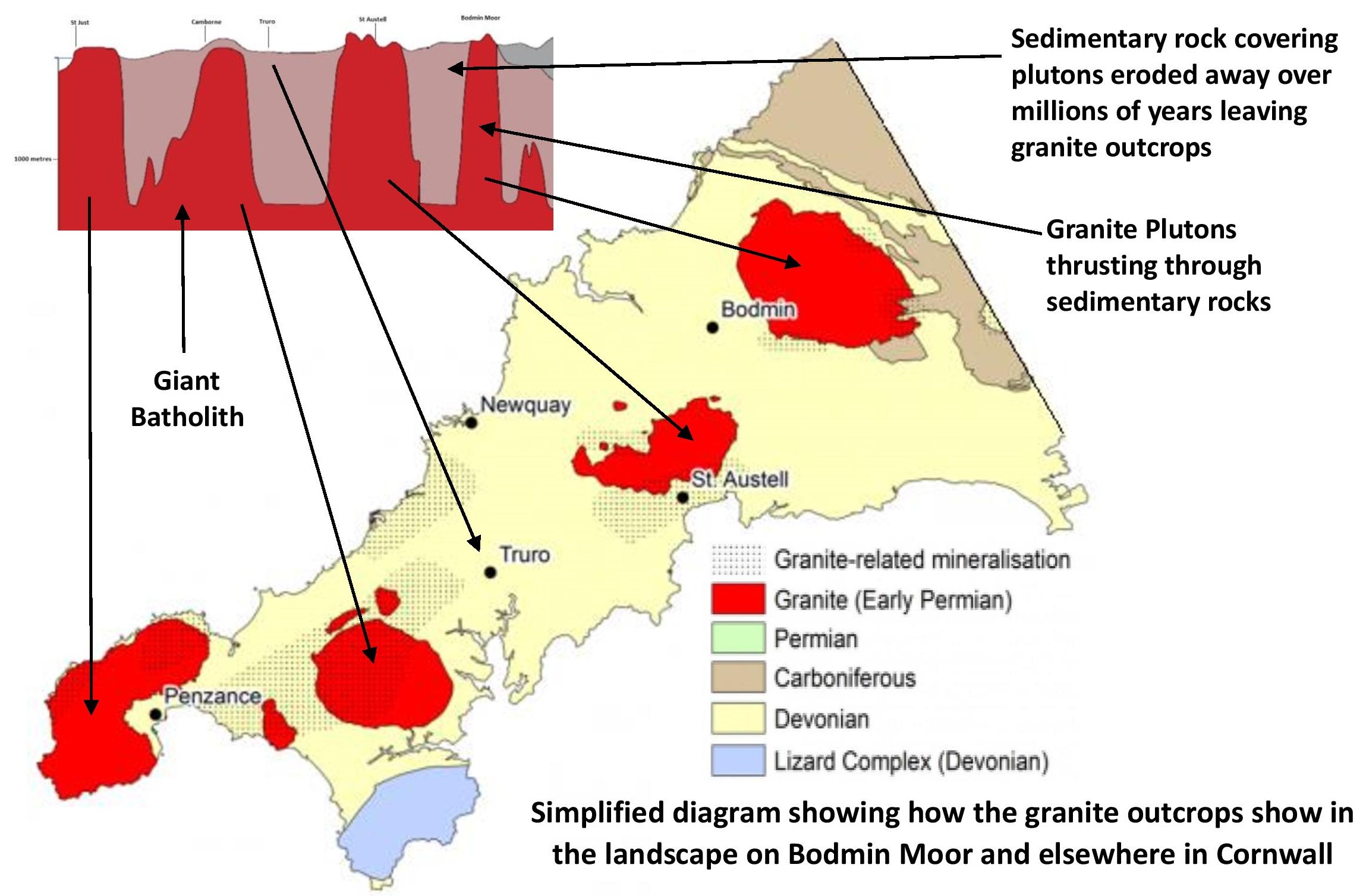

The past and future wealth of Cornwall lies many thousands of feet below the surface. Here lies the giant Cornubian Batholite stretching from Dartmoor throughout Cornwall to the Isles of Scilly. There are four major granite plutons thrusting up through the sedimentary rock to the surface of Cornwall, creating Cornwall’s foremost mining areas. It is here that Cornwall’s metalliferous mineral deposits can be found with their close spatial connections to these granite outcrops. Time has eroded the softer sedimentary rock exposing the top of the plutons where they have come close to the surface. There was sufficient tin deposits close to the surface for early extraction through tin streaming but as these sources became depleted mining needed to be undertaken either by quarrying or mineshafts. Tin then copper led to other minerals being discovered and uses for them found.

Thank you for reading the online version of the Ertach Kernow weekly articles. These take some 12 hours each week to research, write and then upload to the website, and is unpaid. It would be most appreciated if you would take just a couple of minutes to complete the online survey marking five years of writing these weekly articles. Many thanks.

Click the link for survey: Ertach Kernow fifth anniversary survey link

As always click the images for larger view

One of the by-products of mining tin and especially copper mining was arsenic, highly poisonous and rather unwelcome until commercial uses for it were found. For many centuries as an alloy with other minerals it was used for agricultural purposes as poison for vermin, insecticides also embalming. Adding it to wallpaper paste it brought out certain colours as well as dyes in the cotton industry. More recently, but now disused, in ceramic glazes, optical glass and taxidermy. Some Cornish mines relied heavily on arsenic production once the copper began to run out. The 1870’s saw just a few mines in Cornwall produce over half the world’s arsenic.

A mineral map of Bodmin Moor, one of the four major plutons, illustrates that further away from the granite area were the lead and zinc deposits. Whereas the centre shows deposits of tin further out tin became joined by copper deposits. Around the edges of the granite region of Bodmin Moor lie the deposits of lead, zinc and wolfram, perhaps better known as tungsten. Lead has been known from ancient times and is found in the ore galena which often bears silver, a far more valuable mineral. It was widely used by the Romans who mined it, along with the silver, using it extensively. Its many uses have included pellets, batteries, pewter, in paint and petrol, pipes as well as roofing on large buildings such as churches. Incidentally it is from the Latin word for lead, ‘plumbum’, that we get the English word plumbing. The poisonous nature of lead was researched in the late 19th century and seen its domestic uses reduced, although still valued in industry. Perhaps at some point there could be a resurgence of Cornish lead mining. The South Phoenix mine was primarily tin and copper, but within its vicinity lie quantities of heavy metals possibly in greater demand today. I wonder how much useful elements are contained in the millions of tons of waste from early mining throughout Cornwall.

Zinc found in the outlying areas away from the granite plutons is an important trace element for life generally. Again this metal was known to the ancients of Greece and Rome and used as early as 3000BCE in making brass an alloy of copper and zinc. Not as hard as bronze its uses have been ornamental and a wide range of domestic and household uses including musical instruments. Where would our Cornish brass bands be without zinc and copper. Zinc is essential for health and lack of it causes many issues affecting millions of people worldwide, it is commonly used in tablet form as a mineral supplement. Although today it is highly unlikely that zinc itself would be mined here in Cornwall it could still be utilised as a by-product should older mine working areas ever become viable.

Tungsten has the elemental symbol W for wolfram by which name it is often known. It is one of the minerals that the UK government is particularly excited about and why Cornwall is valued by them for its mineral resources. Found in compounds with other elements it was identified in 1783 and has gradually become increasingly used due to its hardness and high density. Perhaps best known to many is tungsten’s use in darts where it revolutionised the manufacture especially for professional players. Of all pure metals tungsten has the highest melting point and alloying it with other metals such as steel gives that product greater strength. It hardly reacts to anything and is immune to most acids and today its commercial uses include in manufacture of computers, mobile phones and motor vehicles. Used in weapon manufacture during the two world wars its uses have increased even further with modern weaponry. This is where Cornwall comes into its own with tungsten deposits available here. In 2003 a Cornish farmer discovered what has become known as the ‘Trewhiddle Ingot’ what appeared to be a relatively small rock. The weight of it was 42lb, which he then used as an incredibly heavy doorstop until his son, a scientist, discovered its true form as fifty percent pure tungsten.

The Cornish geologist Professor Colin Bristow has said ‘Wolframite and tin ore have the same density and they couldn't separate them’. It is likely that the production of this ingot was an accident as wolfram ore when discovered was discarded as a nuisance. Only about four miles distant from the discovery point of the ‘Trewhiddle Ingot’ was Cornwall’s premier wolfram mine at Castle an Dinas, near St Columb Major. Historically the Castle an Dinas mine was the only one in Cornwall established for the sole purpose of mining tungsten. Operating intermittently from 1916 it eventually closed in 1957 following more intensive mining operations towards the end of its existence. There are deposits to the west of Altarnun and around Minions Today there is The Redmoor Project located between the village of Kelly Bray and Callington exploring for tungsten, tin and copper is owned by Cornwall Resources Ltd. It is believed that this site has the potential to supply a substantial part of the UK tungsten needs.

Now looking to the future Cornwall is thought to be able to supply a huge amount of the country’s lithium requirements. This is a new industry for Cornwall and Cornwall Lithium Plc has projects that are highly important for Cornwall and the UK. Their Trelavour Lithium Project has seen the re-purposing of a former china-clay pit near St Austell which will produce lithium through hard rock extraction. Another of their projects relates to the extraction of lithium from deep, naturally circulating waters located at multiple Cornish sites.

On 22nd November the UK government published its ‘Vision 2035: Critical Mineral Strategy’ with Industry Minister Chris McDonald visiting Cornwall to launch it. This sets out how the UK will grow domestic production using international partnerships in supporting the country’s resilience in its ‘Industrial Strategy’ growth sectors. That Cornwall will feature is undoubted as it is stated several times. The policy documents mentions that the ‘UK has distinct pockets of mineral wealth with a deep mining history’. Here only five regions are noted with Cornwall contributing three minerals, tin, tungsten and lithium.

The ‘Critical Mineral Strategy’ policy is linked closely with ‘The UK’s Modern Industrial Strategy’ published in June 2025. From Cornwall’s perspective there are plenty of mentions of how communities will benefit. Quoting the Industrial Strategy it states, ‘The Industrial Strategy is unashamedly place-based, recognising that stronger regional growth is critical for the competitiveness of the IS-8 (eight sectors with the highest potential..) and the resilience of the national economy: we will therefore focus our efforts on the city regions and clusters with the highest potential to support our growth-driving sectors, in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.’

On 27th November Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves announced the creation of the ‘Kernow Industrial Growth Fund’. Funding amounts to £30 million and will be devolved to Konsel Kernow between 2026 and 2028. This will devote to and encourage further investment in a variety of activities and infrastructure driving growth in Cornish industry including mineral extraction.

South Crofty Mine to reopen

One hopes this is not trying to buy Cornish people off from other demands and history should warn us that the benefits of Cornwall’s minerals does not necessarily filter down to ordinary Cornish people. Will benefits to Cornwall be the continued construction of housing ordinary Cornish folk can’t afford with plum industry jobs going to workers from elsewhere in the United Kingdom? Only time will tell but ultimately it’s up to Cornish organisations, businesses and people to engage and ensure they really do benefit from potential future opportunities.